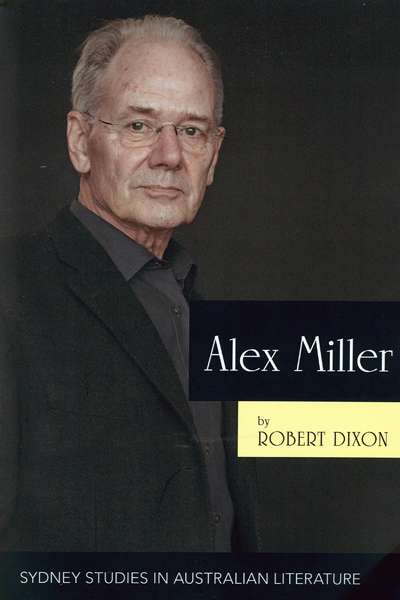

Alex Miller

Alex Miller (1936–), is an Australian novelist. His first novel, Watching the Climbers on the Mountain was published in 1988. Since then, he has won many awards for his fiction. He has twice won the Miles Franklin award, for The Ancestor Game (1993) and for Journey to the Stone Country (2003), and also twice won the Christina Stead Prize for ...

There is no recommended apprenticeship for writers. Nor are there any prescribed personal or professional qualifications. Hermits, obsessives, insurance clerks, customs officers, women who embroider, men who write letters, public servants, soldiers, drunks, provincial doctors and gulag inmates have all become great writers. How? A mystery. But avidity – about the ...