News deserts: A worrying portent for our democracy

Listen to this essay read by the author.

During my first month as a trainee journalist at The Sun-Herald newspaper in Sydney, I went on strike. It was the year 2000, and the newspaper enjoyed a full roster of reporters and photographers dedicated solely to one edition each Sunday, yet even during this well-resourced period there were inklings of the headwinds to come.

The Fairfax (now Nine Entertainment) chief executive officer at the time, Fred Hilmer, had alienated many reporters with plans to modernise the old mastheads in a manner that staff worried would put profits before quality. Word spread quickly that Hilmer had called reporters ‘content providers’ and referred to the newspapers as ‘advertising platforms’. Aggrieved journalists downed tools and my fellow trainees and I dutifully joined the striking workers on the picket line. Afterwards, we bought some cheap bottles of wine and drank them in the Royal Botanic Gardens, privately hoping that the strike would end soon so that our meagre trainee wages would be reinstated, thereby sparing us the indignity of moving into the gardens more permanently.

Two decades on, the protestations of my journalism colleagues appear like the minor gripes of an industry that has lost a much larger fight. The terminology hardly matters anymore, nor would the phrase ‘content provider’ be viewed nowadays as a slight against the media’s overarching mission to challenge and inform. After all, it matters little what the chief executive calls the profession if there is no one left to perform the work, or worse, if the media outlet ceases to exist.

At the beginning of March, it was announced that Australian Associated Press (AAP) will close, abruptly ending the eighty-five-year history of the respected newswire and further narrowing an already concentrated media landscape, dominated, in print at least, by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. Veteran reporters who thought they were inured to the upheavals of their industry – who have witnessed decades of cutbacks, sacked co-workers, closed international bureaux, and a revolving door of executives – were shocked by the dissolution of this largely invisible but vital service. I was among the crestfallen, having spent four instructive years as a court reporter for AAP a decade ago, but my shock no doubt paled in comparison to the grief felt by the 200 or so current reporters whose jobs are threatened.

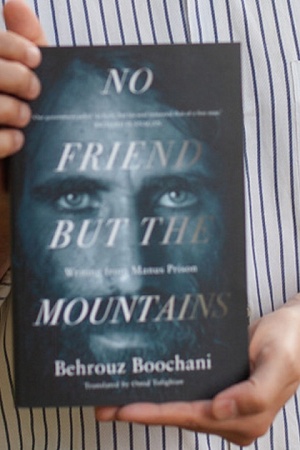

Labor MPs hold up signs in support of Australian Associated Press (AAP) during House of Representatives Question Time at Parliament House in Canberra, Tuesday, 3 March 2020. (AAP Image/Lukas Coch)

Labor MPs hold up signs in support of Australian Associated Press (AAP) during House of Representatives Question Time at Parliament House in Canberra, Tuesday, 3 March 2020. (AAP Image/Lukas Coch)

Predictably, a public brouhaha has commenced over who is to blame, with AAP’s major shareholders, News Corp and Nine, pointing the finger at the proliferation of free news on social media and digital-content aggregators, while the journalists’ union, the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA), has suggested that the reported closure was designed to thwart Nine and News Corp’s rivals, who also subscribe to AAP. Most recently, a potential lifeline was thrown to reporters when multiple parties expressed an interest in buying AAP. It’s a heartening development, but somewhat tempered by chief executive, Bruce Davidson’s, warning to staff not to get their hopes up: ‘I must stress that at this stage we have no understanding on the viability or otherwise of these approaches,’ he said.

There is talk of trying to patch together some weak substitute – News Corp and Nine are considering developing in-house breaking news services – while discussions were reportedly held to establish a cooperative among the remaining small subscribers to pool news and photography resources. If AAP fails to find a respectable buyer or some limp iteration takes its place, it is abundantly clear that the loss will have widespread ramifications for the media’s ability to fulfil its charter to inform the citizenry and to keep a vital check on power. The major mastheads all subscribe to AAP, as do smaller and newer players, including Verizon Media, regional papers, radio, and, to some extent, The Guardian. Newsrooms across the country have shrunk at an alarming rate over the past two decades, with data showing the number of journalists in traditional print businesses fell by twenty per cent from 2014 to 2018 alone, as outlined in the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) ‘Digital Platforms Inquiry’ report.

Yet AAP journalists, burdened by their own staff cutbacks, have continued to turn up to court cases, royal commissions, council meetings, and coronial inquests, informing Australians on what is happening in their communities, judicial system, and tiers of government. It is the kind of methodical, serious, deeply important work that buttresses a free press. Wire journalists do not need to fill blank pages like their colleagues on a news masthead, which means that there is very little pressure to cook up a specific angle. AAP is owned by four media outlets, with rivals Nine and News Corp holding the largest stake, and the wire service’s need to cater to a range of subscribers ensures that it has never taken a distinct editorial line. News wires, furthermore, are immune from the commercial need to attract advertisers. This liberates journalists from the weak will of nervous editors who cannot hold the line against commercial pressure to kill or limit a damaging story.

AAP also plays a fundamental role in its indirect support of long-form investigative work. A number of fine wire reporters have broken exclusives, but it’s been AAP’s broader role in helping to free up subscribers’ newsrooms for deeper fact-finding that has made it such an asset. This deep investigative work is invaluable, especially in light of the federal government’s hostility towards media probing and accountability, which has only increased in recent years. In the past year alone, Australian Federal Police (AFP) officers have raided the home of a News Corp journalist and the ABC Sydney office in relation to exclusive and damaging stories, while the Australian Signals Directorate Director-General, Rachel Noble, recently admitted to a Senate estimates committee that the ASD had spied on Australians, claiming they were ‘rare circumstances’. In 2016, journalist Paul Farrell, formerly of Guardian Australia, discovered the AFP had attempted to identify and prosecute his confidential sources by seeking to access his metadata without a warrant. Meanwhile, journalists are continually frustrated in their efforts to access information through the obstructive and clunky Freedom of Information (FOI) apparatus, the prime minister, Scott Morrison, refuses to answer questions over the sport grants affair, and we still lack a robust federal anti-corruption body, with the government proposing a toothless Commonwealth integrity commission instead. These are but a handful of worrying examples of creeping government intrusion, obfuscation, and overreach, and it is not difficult to imagine how an impoverished reporting climate and the loss of a major news player will further hobble the media’s ability to hold the powerful to account.

The crisis becomes even more acute when you consider that many Australians receive their news through a limited range of sources, including uncredentialed stories on social media. According to the findings of the 2019 ‘Digital News Report’, coordinated by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, Australians are less engaged with news than citizens of other countries. The report found that, compared to the citizens of thirty-seven other countries, we are less likely to check the accuracy of a story and we use fewer sources to access news. This trend was visible during the recent Black Summer bushfires, when an analysis by BuzzFeed found that some social media accounts were spreading information and images of the fire that were false, misleading, or unverified, including the widely circulated lie that Greens MPs oppose hazard-reduction burns.

While many commentators agree on the need for reliable news sources, few can agree on how to fund it, with the social-justice principles of journalism seemingly out of step with the commercial imperative of modern business. MEAA Chief Executive Officer Paul Murphy has argued that the government must intervene to protect public-interest journalism through a levy on a percentage of the digital revenue that the likes of Google and Facebook make from their use of news content. Chair of the Public Interest Journalism Initiative (PIJI) Allan Fels has similarly called on the government to step in with potential tax rebates that he says could inject up to $380 million into public-interest journalism. The editor-in-chief of AAP, Tony Gillies, told ABR that he doesn’t believe it is the role of the government to support news, but thinks more needs to be done to rein in Google and Facebook. ‘I can see the case for a short-term [government] funding boost to a new entrant, but long-term I think it’s the government’s role to act primarily to ensure a level playing field,’ said Gillies, referring to the advertising revenue Google and Facebook make from mainstream media content. ‘To be honest, this problem began when we in the media started giving our content away for free online, and now it is like trying to get the toothpaste back into the tube.’

On the day AAP’s closure was announced, Morrison and Federal Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese stood up in Parliament to express their sympathies for sacked staff. Albanese listed the names of the AAP Canberra bureau staff one by one, solemnly paying his respects to journalism’s most recent casualties. I don’t doubt the sincerity of the sentiment, but there is no clearer sign of the Fourth Estate’s growing impotence than the sight of MPs offering their pity and condolences up to its charges.

Our democracy will be weakened if AAP closes its doors, creating news deserts in our communities and entrenching social media’s panicky echochamber of likes, shares, and viral outrage in its place. Meanwhile, the nation’s most pressing stories will be left untold.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.