'Letter from Athens' by Scott McCulloch

Behind Omonoia Square I check into a cheap hotel, one that mainly sleeps prostitutes and their customers. The receptionist is worn – nicotine fingers, few teeth, sharp cheekbones, gaunt features. His flesh is as green as old tattoos. Leading me down the dank hallway, he lifts up his G-Star Raw T-shirt and scratches a large tattoo of a skull heaving angels from its mouth.

Men argue on the streets below. Various languages adorn closed shops: Bengali, Urdu, Georgian, Albanian. Two prostitutes are hooking strangers in the shadows. They offer a threesome for twenty euros. I drink a small bottle of ouzo in bed as the banter continues. Theo Angelopoulos’s film Eternity and a Day (1998) plays on my laptop. The narrator recites, ‘Time is a child that plays dice on the shore.’

I head to Syntagma Square, where the pensioner Dimitris Christoulas shot himself in 2012, illustrating the human cost of austerity. An old man with placards in A4 plastic pockets attached to him inveighs by the fountain. He needs some kind of surgery that the health care system cannot provide.

A honky barrel organ on a cart passes by. The disjointed cacophony of piano, harpsichord, and bells, stuck in broken repetition, addresses the morning. Akin to the raucous peals and hammers of the instrument, something that is ancient and broken, it is the avidity within this decay that has attracted me to the so-called cradle of democracy – to witness how it somersaults through its current abyss.

Flicking through Henry Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi (1941), I find this wayward premonition of the iron cage of the eurozone:

It is a trap devised by Nature herself for man’s undoing. Greece is full of such death-traps. It is like a strong cosmic note which gives the diapason to the intoxicating light world wherein the heroic and mythological figures of the resplendent past threaten continually to dominate the consciousness … All Greece is diademed with such antinomian spots.

I stroll around the streets that lead from the square. Protest groups in tents occupy a squalid corner, opposing the colony of creditors. The forlorn faces of the protesters reflect their stifled efforts.

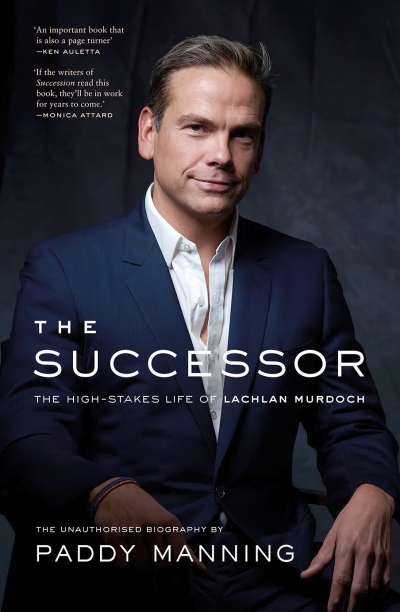

Athens shop window (photograph by Scott McCulloch)

Athens shop window (photograph by Scott McCulloch)

Closer to Monastiraki square, the roots of a large tree burst through the pavement. The organ grinder locks eyes with me each time he passes by.

‘Yasou,’ I call out in a darkened hallway. I have walked into a building that supposedly houses an art gallery in Metaxourgeio. All I hear is loud techno. Opening a door I find a deserted dance floor with disco lights and a stage for pole dancing. I stand in the desolate strip club.

Abandoned shops line much of this old promenade. Red lights dangle above the doorways; all these buildings are brothels. There are at least thirty on this one strip. Sitting in a small takeaway shop, I order gyros and watch the trade unfold. A young man wearing a T-shirt with a cheetah on it, a necklace with a live bullet on the end, and carrying a 500ml can of energy drink in his hand walks into one of the buildings with boarded-up windows. A thick-set woman upwards of fifty patrols up and down the promenade, slipping cash and condoms into the hands of women. Her taut lips clasp a hand-rolled cigarette as she commands the air.

‘Leading me down the dank hallway, he lifts up his G-Star Raw T-shirt and scratches a large tattoo of a skull heaving angels from its mouth’

A woman in her late teens walks past, a grey top cropped beneath her breasts. Her belly is tattooed with a triangular design of serpents entangling the Lord’s son. I watch the tattoo move with the skin and think of how the euro has been described as a straitjacket for Greece; how Greece can be thought of as the hefty ballast of the sinking ship that is the eurozone.

A man with two Discmans in his tracksuit pockets passes by mumbling to himself. He is listening to each of them; apparently listening to two different songs. A stream of gibberish spills from his mouth as he tries to sing both of the songs at the same time. He slams his fist down on my table and asks for money.

I leave the café and walk through a city in a state of gradual decomposition. Black chewing gum stains the footpath concrete. A static electrical hum sounds through the streets. I pass an expensive tavern filled with tourists. Across from the restaurant, in broad daylight, a group of four men snort lines off a doorstep.

and a breeze so fresh it lifted the lace curtains

like a petticoat, like a sail towards Ithaca;

I smelt a dead rivulet in the clogged drains.

(Derek Walcott, Omeros)

During the night I am woken by the sound of another guest vomiting in the shared bathroom sink. I decide to leave the hotel.

I board a train to Patras. Several times we are shuffled onto different trains because of electrical faults. Noticing that I am lost, a young woman named Immanuela shows me where to go. We sit quietly and watch the rushing coast. Between the foliage that shimmers through the train window, a man douses kerosene on his lemon trees and ignites them. Immanuela says that if I am going to Patras I should catch a boat to Italy. I tell her that I am here to be in Greece. Immanuela seems confused: ‘Why did you come now?’

‘During the night I am woken by the sound of another guest vomiting in the shared bathroom sink. I decide to leave the hotel’

Our conversation inevitably becomes political. We begin talking about the neo-Nazi/fascist political party, Golden Dawn, whose insignia incorporates the swastika. Many of the party’s politicians have served time. Immanuela describes Golden Dawn’s recruitment techniques. Like many extremist groups, they prey on the impressionable and the vulnerable.

‘They go for the young, teenagers, usually sixteen- or seventeen-year-old boys who don’t know what they want and who know that there are no jobs for them; who have brothers and sisters who have postgraduate degrees and are still unemployed; who are angry with who they are and where they find themselves, without a choice. It works. It’s terrifying.’

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

Immanuela has recently left her native Crete. ‘I would like to host you on the island and show you renowned Cretan hospitality, but I don’t have a house anymore.’

‘Do you want to have sex with me?’ A middle-aged man wearing a pair of underwear and thongs asks in the doorway to my room in Patras.

‘I’m flattered, but I’m fine, thanks.’

He is Portuguese but wanted to leave Lisbon.

‘I came here because there’s no work in Portugal – and there’s no work here. I don’t want to work but I thought it would be easier to live here because it would be cheaper, but it’s not. Is Australia a good country?’

‘It depends on who you …’ I stop. ‘That’s a difficult question.’

‘I think New Zealand is a better country, yes?’

‘Sure.’

In the morning, the receptionist bursts into my room, beaming with confusion: ‘Why didn’t you lock the door?’

I am staying in another hovel: something akin to the Gatwick Hotel in St Kilda, except there are few guests and it is in Patras. The doors to the rooms slam on their own volition. The outside of the fridge is lined with black mould. Inside the fridge sits a pair of filthy socks. An old phone rings erratically throughout the night. The owner sits on his bed eating small fish and watching television.

The one-eyed man in the other room screams ‘pousti malaka’ at his dog for most of the time. A fuzzy television tries to play the news. At least twenty plastic bags are on his bed. He sees me and says, ‘Philo friend friend philo, welcome!’ He kicks a dustpan down the stairs, goes back to his room, and continues to scream at his dog.

It rains the whole time I am in Patras. I watch it pelt into the Mediterranean and turn the air into acrid colours. Night falls. Half-empty trucks file down the orange-lit highway and slowly board the ships for other countries.

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

I make my way back to Athens. On the bus to the train station I see a drained swimming pool with tall stalks of yellow weeds spiking from the floor tiles. Three young boys sit by the pool on their BMXs, looking in different directions from one another, doing nothing.

The road is sublime. The water and the land and the islands that resemble volcanic icebergs intersect and skewer one another, almost lacerating the sky. House after house have their shutters drawn. I recall someone saying that as many as 300,000 Greeks have left Greece since the crisis.

A woman comes up to me on the station and asks in English: ‘Are you Orthodox?’

‘I don’t know,’ I say.

The woman hovers silently by my side. The regional train pulls in with its elastic gait.

‘Night falls. Half-empty trucks file down the orange-lit highway and slowly board the ships for other countries’

I accidentally break into a deceased estate. Orthodox icons and decaying family photos line the walls. There is dust in the bath and an unmade bed. The power and water are still on. I wash my face as shafts of parched light cuts through the twisted venetians. I wonder how many deceased estates and empty houses there are like these around. I return to the stairwell and replace the lock.

I meet Maria Rota and the stray dog she has adopted. Maria, a psychologist, volunteers at the Metropolitan, a free medical clinic that has opened since austerity strangled healthcare funding.

I tell her that it seemed strange watching the recent election from abroad. All that many of us could gather was that the political situation was just as bad, if not worse, than economic realities. The hard-left party of Syriza seemed to appear from nowhere. I tell her that it was inspirational to watch Syriza being sworn in; it encouraged me to think that the dire state of Australian politics could be changed.

Maria notes the comparison. ‘In Australia I always felt like I was doing something wrong.’ I laugh. ‘Things happened because they had to. Greece has to figure itself out internally. Then Germany will be a breeze.’

As we sip our coffee Maria constantly greets passing friends. She continues: ‘History plays a role for how we have gotten to this position. There was no renaissance here – we were occupied by the Ottomans at the time. We’ve had a tough history – wars with others and ourselves; not to mention the time of the generals – but it should be a reality more than an excuse.’ Maria pauses. ‘What happens when you give a seventeen-year-old everything?’

I/ came/ to a ward of horses,

bloated on cake, relaxed in front of, t.v.s

the king of kings, their therapy

wax horses, wax horses

the city is burning its horses

(π.O., ‘Supermarket’)

Convoys of riot police buses with caged windows storm through the streets, en route to the first day of the Golden Dawn trial.

I visit the anarchist neighbourhood of Exarcheia. I see an abandoned butcher shop. The meat has vanished but the smell lingers. Next to the shop a man shoots up heroin. A Roma couple laugh hysterically as they run around a dumpster and throw large chunks of pork fat at each other.

In the main square of Exarcheia, students, immigrants, drunks, and homeless people of all ages sit in the sun, swilling beer and smoking hashish. Everyone seems to know one another. In the centre of the square is a statue of a naked winged baby doused in black paint.

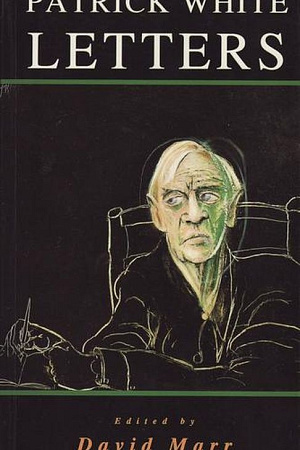

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

(photograph by Scott McCulloch)

I cross town. On the metro a man has passed out with an open cap on the floor beneath him. There is a chunk of hair the size of a fist missing from the back of his skull, exposing a purple-white circle of grafted flesh.

I meet the actor, artist, and multi-platform theatre-maker, Marilli Mastrantoni, who tells me about the acronym of PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, Spain); it circulates among the wealthier countries of the EU. Marilli likens the crisis to a stroke. I think of an ambulance broken down in a field of poppies.

As dusk rolls over the city, lights beam upon the Acropolis.

The trial was adjourned.

I check into a cheap hotel in Metaxourgeio. It is close to one in the morning and Reception is empty. A thin man drinking beers asks, ‘You looking for a room, brother?’ He talks fast, eyes darting to something above my head. He checks me into a dorm and asks me where I am from.

‘I recall someone saying that as many as 300,000 Greeks have left Greece since the crisis’

‘I thought you were Greek for a minute, brother. I know there’re a lot of Greeks living in Melbourne. Australians always tell me how Melbourne is the third biggest Greek city, after Athens and Thessaloniki. You know that, brother? The Australians always feel like they have to say that. Anyway, my name’s Mehdi, I’m from Tunisia. You hungry, brother?’

I buy beer and Mehdi cooks pasta with bolognese sauce. He works the night-shift: twelve hours a night for ten euros. ‘It is not enough, brother, but it is more than what a lot of people have. Besides,’ he whispers: ‘I’m not supposed to be here.’

We drink into the night as plumes of smoke and insects make knots around the light in the kitchen. Mehdi smuggled himself out of Tunisia when the Arab Spring swept through his country. With his eyelids gently drooping as the alcohol and the late night takes hold, Mehdi says: ‘Nobody predicted what happened in my country … with the Spring. I think it could happen here.’

I am no longer in Greece. I continue to follow the saga of the crisis. A contrite Athens seems to be the desire of the EU empire. The crisis has paved the way for much prejudice and racism and accusation; as though the populous should be held accountable for the profligacy of their government. The decay and misery I witnessed indicated that Greek society is in ruinous flux. But energy still pulses amid the oblivion.

I pick up Henry Miller’s novel and read: ‘Greece has emancipated itself as a country, a nation, a people, in order to continue as the luminous carrefour of a changing humanity.’

With this in mind, but resisting any implied nationalism, I gaze on as the Greek crisis alters the future of Europe.

In an online video, Alexis Tsipras is speaking at a conference in Zagreb. Mehdi’s voice is echoed as Tsipras espouses his wishes for a ‘Mediterranean Spring’.

Despite the prospect of Greece being a realm of ancient waste – suspended into generations of economic collapse – democracy prevailed on 5 July when the great majority of Greeks voted ‘Oxi’ in a historic referendum. Yanis Varoufakis has stepped down as the finance minister. ‘Grexit’ and the restoration of the drachmas are distinct possibilities. Yet it is all purely guesswork from now. Alarm is rife throughout the eurozone.

I think of Angelopoulos’s narrator: ‘Time is a child that plays dice on the shore.’

Comments (5)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.