- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Features

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A sanitised version of a great contrarian

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Pauline Kael did not shy away from big statements. She said that the release date of Last Tango in Paris would be as historically resonant as the night The Rite of Spring had its première, and she described Fiddler On the Roof as a movie of operatic power. As a film reviewer at the New Yorker from 1967 to 1991, she was a significant cultural figure, particularly in the 1970s, when her influence was at its height. It is for her extremes that Kael was celebrated and feared, for her exuberantly adversarial prose, and for the ferocious expression of her cinematic loves and hates.

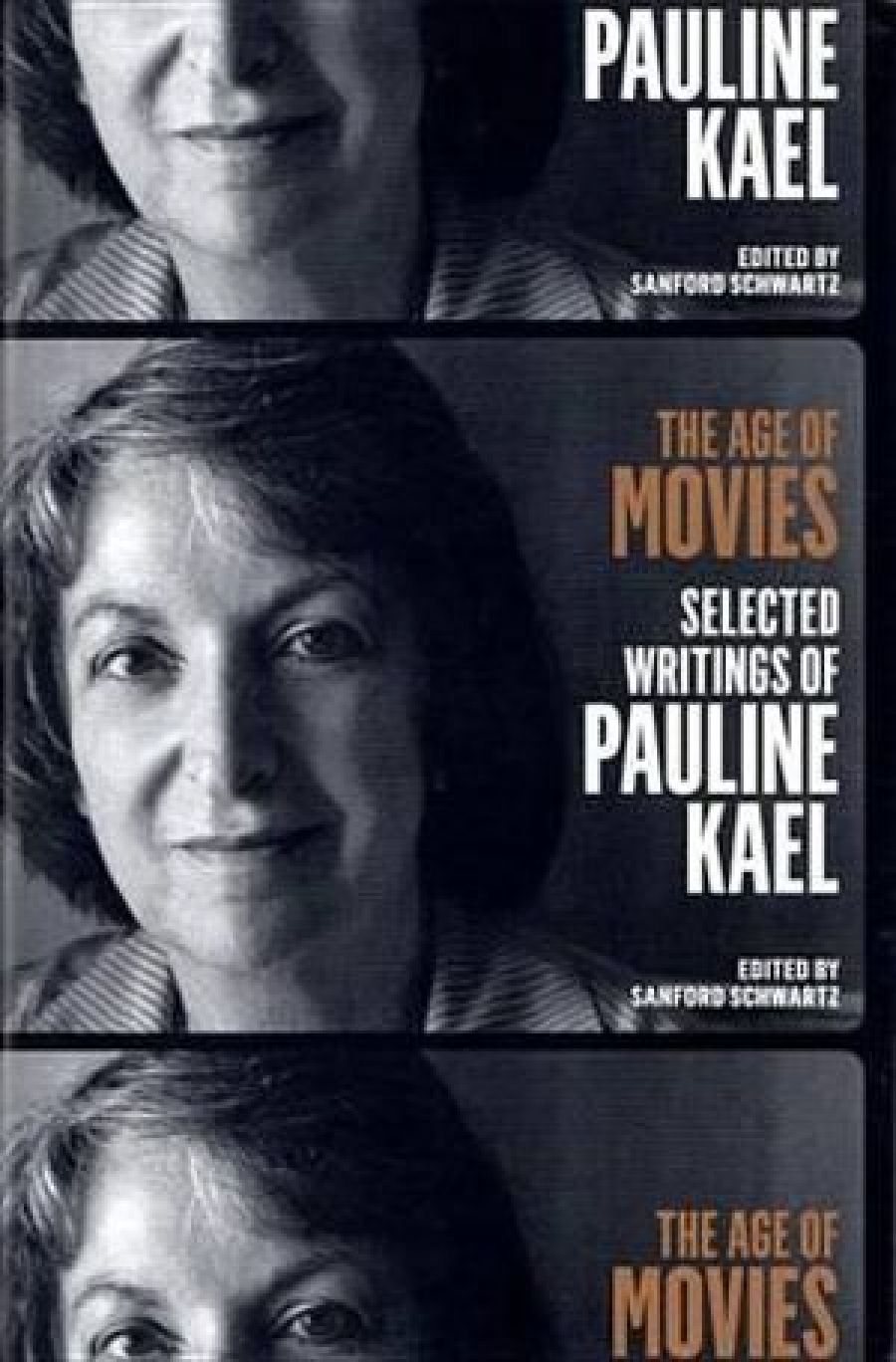

- Book 1 Title: The Age of Movies

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected writings of Pauline Kael

- Book 1 Biblio: The Library of America, US$40 hb, 852 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-age-of-movies-selected-writings-of-pauline-kael-pauline-kael/book/9781598535082.html

The Age of Movies, edited by Sanford Schwartz, consists of almost one hundred reviews and articles that appeared between 1959 and 1990. Kael wrote for many magazines and had a five-year stint on public radio before she was appointed to the New Yorker in her late forties. She already had a public profile, with a bestselling book of reviews, I Lost It At The Movies, which came out in 1965. But the New Yorker gave her status and a long-term institutional base. And it gave her space, which now seems like a remarkable luxury; these days the long-form film review feels like a distant memory.

One of Kael’s best-known early pieces is called ‘Trash, Art and the Movies’ (1969), and the relationship between those three terms is one of the eternal themes of her work. She explored this in an idiosyncratic way. Readers had to be alert to the fact that when she called a film ‘shallow’ she generally meant it in a positive sense, and when she described a movie as ‘serious’ it was almost always a putdown. When she said that director Stanley Kramer ‘strove to make films about important ideas’, it is clear that this was a damning assessment.

Kael saw herself in combative terms, setting herself against the assumptions of others. She wrote in the essay that opens The Age of Movies: ‘[I]n Hollywood, one must often be a snob; while in avant garde circles one must often be a Philistine.’ That dissenting imperative, that apparent delight in being the contrarian at the party, is evident throughout her work.

Kael wrote at a time when there were rich new voices in American cinema; she championed many of them and skewered others. She also issued regular jeremiads about the dire moral and creative state of Hollywood. She had a talent to amuse, and to abuse; she seemed to relish feuds with other reviewers. Although she became one of the magazine’s stars, she thought of herself as an outsider within the New Yorker, at odds with its perceived image of patrician, East Coast intellectual superiority.

‘My worst flaw as a writer,’ Kael said, looking back on her career, ‘was reckless excess, in both praise and damnation.’ Reviewing her massive 1994 ‘best of’ collection, For Keeps, in the New York Review of Books, Louis Menand added a twist, suggesting that ‘her habit of overpraising and overdamning was itself overpraised and overdamned’. When Kael died in 2001, the tone of many obituaries implied that her significance had waned abruptly; that she was barely known to the current generations of film-goers and readers who came after her. Yet she is often cited as a mentor to many of the next generation of American reviewers.

Kael is generally thought of as a director’s champion, a cheerleader for new boys in town: Robert Altman, Sam Peckinpah, and Brian De Palma, in particular. Yet, as Schwartz points out, her imagination is more intensely compelled by actors, from the figures of current cinema to the stars of old Hollywood. In The Age of Movies, a series of reviews vividly evoke the performances of Marlon Brando, but there is also an extended, graceful celebration of Cary Grant, and a review of Gillian Armstrong’s High Tide (1987), in which she is passionately appreciative of the work of Judy Davis and Jan Adele. She had her whipping boys; she was hard on Meryl Streep (although you can’t really tell from this selection), and Clint Eastwood was another who felt her scorn (Eastwood, she writes, ‘isn’t an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor’).

Kael built her criticism, Schwartz says, ‘on her most spontaneous and sensory reactions’; she granted primacy to her immediate, visceral response to a film, and put all her energies into conveying this. One of her trademarks is the frequent use of the second person, in a manner that comes across as both inclusive and coercive – those extended, heightened descriptions of how ‘you’ feel as an audience member. And she is constantly reaching for the superlative, no matter how absurd or pointless it might seem, for example, to pronounce the finale of De Palma’s 1978 thriller The Fury as ‘the greatest finish for any villain ever’.

The Age of Movies is published by Library of America, a non-profit organisation set up to produce ‘authoritative texts of America’s best and most significant writing’. Kael is not the first film reviewer to appear in the series. The complete works of the influential, less widely known critic Manny Farber have already been published, and the film reviews of James Agee and James Baldwin are included in their Library of America volumes. There is also an anthology called American Movie Critics: From The Silents Until Now (2006), edited by Phillip Lopate, which includes four Kael pieces.

Kael’s work was regularly collected during her reviewing years. The Age of Movies draws, apart from its opening article, from ten of her books, thick volumes with titles such as Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (1968), Going Steady (1969), and Deeper into Movies (1973), which consciously suggested an eroticised relationship with the subject. It could also be regarded as an abbreviated version of For Keeps; nine-tenths of its reviews are in that book.

Reading The Age of Movies, I was reminded of why I bought several of Kael’s books many years ago, and why I have rarely returned to them since. The tone of certainty can be seductive, but it is also reductive; it is hard to read her without wanting to respond, to argue back, yet the cumulative effect is exhausting. After a while, too, there is a sense of repetition, of her revisiting the same provocations and obsessions.

Sanford Schwartz, who has also written about art and artists, was a long-time friend of Kael. He provides some interesting background about her early life, but his introduction is dutiful rather than illuminating, particularly when it comes to giving a context to readers new to Kael. He addresses his choices only fleetingly, apart from a reference to omitting her lengthy two-part essay ‘Raising Kane’ for reasons of space. At the same time, he gives a somewhat misleading representation of its controversial account of Orson Welles and his role in the creation of Citizen Kane. The essay has its admirers, but it has been criticised for inaccuracies and, more recently, for unacknowledged use of sources.

All in all, Schwartz presents us with a slightly sanitised version of Kael – he plays down the anger and strong reactions her work often inspired. He could be excused for not mentioning that George Lucas named a villain ‘Kael’ in his 1988 film Willow, and forgiven for omitting to mention Renata Adler’s snooty 1980 takedown of Kael’s work in the New York Review of Books – an intriguing example of a New Yorker writer turning on one of her own. But could he not have referred to or discussed Kael’s differences with critic Andrew Sarris, who introduced the auteur theory to the United States, thereby incurring Kael’s lifelong scorn?

Should Schwartz have included Kael’s 1985 review of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, one of her most controversial pieces? She fought the New Yorker editor William Shawn for some weeks to get it into print, yet she omitted it from For Keeps. I would argue for its inclusion in The Age of Movies – but there is not even an acknowledgment of it. It is not her ‘best’ writing, but its faults tell us something about her significance and her style, her self-conscious contrarianism and her exaltation of the personal response. She felt that the critics who praised Shoah were responding to the film’s subject, the Holocaust, and not to the film itself. But the review is an impatient piece of prose, almost ostentatiously dismissive.

Schwartz chose the title of this collection, he says, because he believes that ‘perhaps more deeply than any other writer Kael gave shape to the idea of an “age of movies”’. Elsewhere, he gets closer to what he has compiled. Her body of work, he suggests, could be seen as ‘a single, long, indirect and utterly original kind of autobiography’. And that’s what this volume projects; not the sense of an era, but the sound of a writer’s voice – rich and intense at times, but also strident, smart, ebullient, overbearing.

Comments powered by CComment