- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The remarkable translator of Erich Maria Remarque

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Arthur Wheen, a nineteen-year-old signaller in the Australian Imperial Force, sailed from Egypt to France in June 1916. A month later he wrote to one of his younger sisters in Australia recounting, in highly fanciful language, his first experience of battle. After describing his difficulties with mud and barbed wire, he told her, ‘I got out in the end though and cantered across to the German trenches where I had much better luck with their barbed wire.’ Agnes Wheen would have had no inkling that her brother had just taken part in a disastrous battle in which more than five thousand Australian soldiers were killed or wounded.

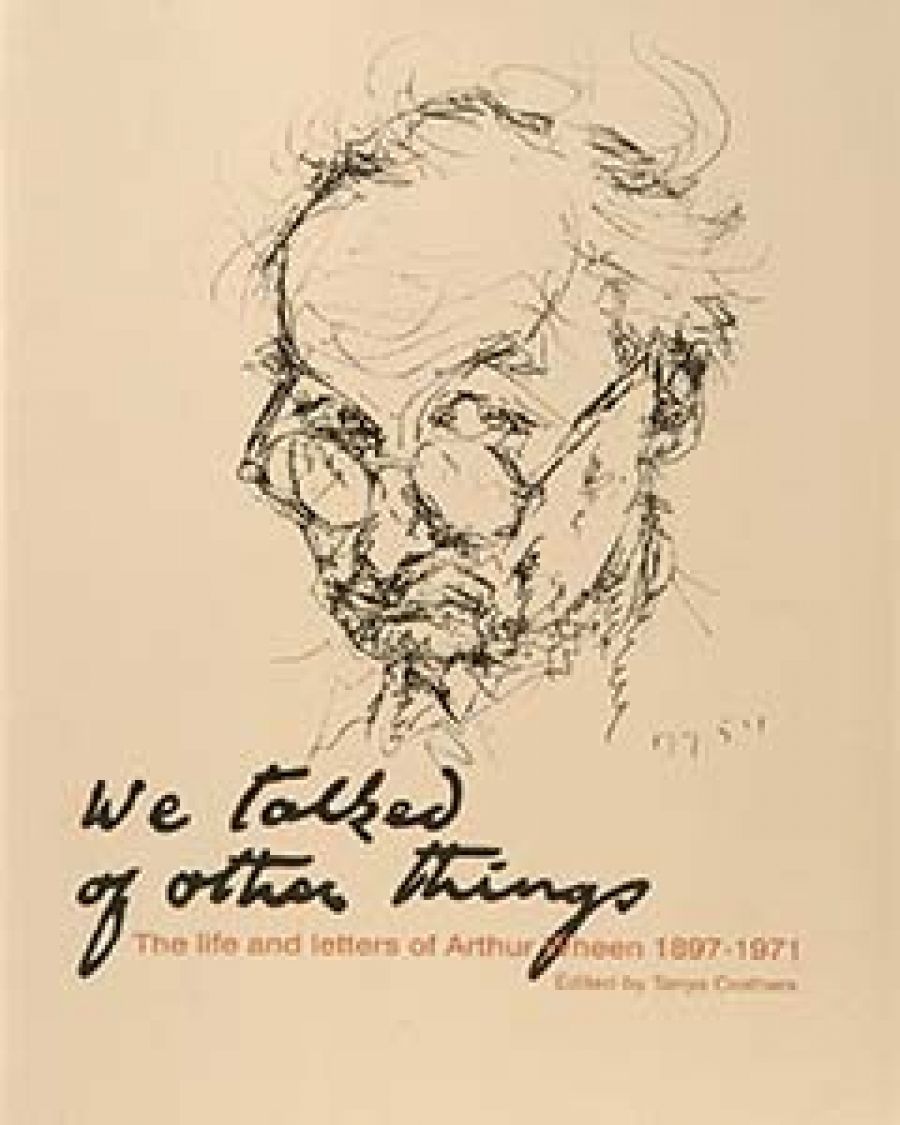

- Book 1 Title: We Talked of Other Things

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and letters of Arthur Wheen 1897–1971

- Book 1 Biblio: Longueville Media, $55 hb, 448 pp

Wheen remained in France for two years. In letters to his father, he occasionally wrote about fear and dismissed the idea that there was anything glorious about the lives of front-line soldiers: ‘they swear and curse and ache and shiver – not heroes, but most miserable creatures.’ He seldom mentioned his own exploits, yet others spoke of his extraordinary bravery. Like Siegfried Sassoon, whose poems he read, Wheen would spend hours on his own in no man’s land, repairing telephone lines and rescuing wounded soldiers. Nominated for the Victoria Cross, he was awarded the Military Medal three times. He was twice wounded, the second time seriously, and was lying in a London hospital when the war ended in November 1918. He never regained full use of his left arm or hand.

Tanya Crothers describes Wheen as ‘a private man shrouded in memories of World War I that are rarely revealed’. The memories returned to him forcefully in 1929 when, on the recommendation of Herbert Read, he began to translate Erich Maria Remarque’s war novel Im Westen nichts Neues (1929). It is not known how Wheen acquired his knowledge of German, although he always had a flair for languages, including Arabic and Chinese. He later wrote to Charles Bean that he understood Remarque’s manuscript ‘less by reason of my knowledge of German, which I have but imperfectly, than by virtue of having made the experience recorded in it ... On the other side of No Man’s Land was, as near as, damn it, our very selves.’ It was Wheen who coined the evocative title All Quiet on the Western Front. As Remarque acknowledged, his translation contributed greatly to the success of the novel. Within a few months, the English and American editions had sold more than half a million copies.

By this time Wheen had settled in England as a permanent expatriate. After leaving Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar, he mixed in literary circles and was encouraged by friends to write a book. A short story was published, but his high literary standards and a tendency to procrastinate (in 1918 he had told his father that he was ‘a living Hamlet’) resulted in a bad case of writer’s block. Instead, he became a librarian at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The job suited him, for he had a strong interest in art as well as literature. He married a fellow Australian, Aldwyth Lewers, the sister of the sculptor Gerald Lewers. She was a passionate gardener and they acquired a small farm on the edge of a Quaker village in Buckinghamshire. They lived there for the rest of their lives.

We Talked of Other Things mostly comprises letters and quotations from letters, interspersed with fairly brief commentaries and background information by Crothers. The letters extend from 1915, when Wheen enlisted in the AIF, until 1970, a few months before his death. The World War I letters take up the first third of the book and will probably be of most interest to Australian readers. The context and the names are familiar: Fromelles, the Somme, Beaulencourt, Polygon Wood, Villers-Bretonneux. Letters written from those battlefields exist in vast numbers, but while they are often poignant they generally lack literary qualities. Paul Fussell, in The Great War and Modern Memory (1975), has written about the formulaic understatement in which the letters of Other Ranks were written: ‘the trick was to fill the page by saying nothing and to offer the maximum number of clichés.’ There was, however, nothing formulaic about Wheen’s letters. They were often very lengthy and revealed his great descriptive powers, his eye for detail, his humour, and his anger, and his sympathy for ordinary soldiers on both sides. Sensitive to the fears of his family, he seldom referred to actual fighting. Instead, he wrote about Egyptian deserts and snow-covered battlefields, the rats and the lice, the mud and slush, forced marches, the bravery of comrades, and the mayhem that existed behind the front lines.

Wheen wrote to individuals, rather than to his family as a whole, and the content, tone, and length of his wartime letters varied, depending on whether the recipients were his parents, younger siblings, his older brother, who was also serving in France, or old schoolfriends. When writing to his mother, for instance, he often recalled happy or amusing times in Australia, avoiding subjects likely to upset her. The postwar selections do not have the same variety. Friends and even most of his siblings soon disappear from the scene. From 1950 onwards, almost all the letters were written to his daughter Gretchen, who had settled in Australia.

The later letters are mostly a record of Wheen’s private life. It was, in many respects, a sad life, as he dealt with financial worries, a difficult marriage, the death of his younger daughter, and worsening health. Wheen did not indulge in self-pity, but he could be self-deprecatory. In 1953 he told Gretchen, ‘I am become conscious that my coat cuffs are frayed; my underpants are full of holes. My bladder is too small. My memory is not good. My hair is growing thin. My name in short is Alfred J. Prufrock.’ Yet the letters were seldom dull and he had the ability to write about simple things – farm work, the daily train journey to London, books, art classes – with imagination, humour, and whimsy. He said, however, very little about his work as a translator or as Keeper of the Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum. His colleagues at the Museum held him in high esteem and, when he retired in 1962, Aldwyth wrote that he had ‘spent his life in wonderful conditions’. But the challenges of his professional work, and the satisfactions that they brought him, are largely missing from the book.

Family letters have their limitations. It is a pity that Crothers did not widen her selection to include correspondence in public collections. There are, for instance, many letters from Wheen in the archives of Marcel Aurousseau and Herbert Read, and it is likely there are others in the large Remarque archive and elsewhere. The letters to Aurousseau, held in the National Library, give the impression that Wheen enjoyed London literary life, regularly lunching with Read, T.S. Eliot, and other writers, attending lectures, passing judgement on new poems and old poets, and continuing his translations of German novels. The inclusion of letters of this kind, combined with the family letters, might have created a fuller portrait of a complex man.

Wheen lived at a time when international phone calls were rare events and when letters were the main form of long-distance communication. It is fortunate that his family admired his writing and kept so many of his letters. Tanya Crothers, who is a niece of Aldwyth Wheen, has based her selection on this family archive and, in filling in some of the background, has drawn on the memories of Gretchen Wheen. She has produced a handsome volume, beautifully illustrated with photographs and drawings. It should ensure that Arthur Wheen is remembered in his native land as an outstanding letter-writer, and not simply as the translator of All Quiet on the Western Front.

Comments powered by CComment