Archive

A Distant Grief: Australians, war graves and the Great War by Bart Ziino

by Ken Inglis •

Modernism & Australia: Documents on art, design and architecture 1917–1967 edited by Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, and Philip Goad

by Anthony White •

The Politics Of War: Race, Class, And Conflict In Revolutionary Virginia by Michael A. McDonnell

by Donna Merwick •

Dear Editor,

Brian Matthews makes an eloquent defence of Manning Clark’s Kristallnacht fantasy, but I was surprised to find myself being drafted as a witness simply because I once said that autobiography is ‘a lying art’ (May 2007). Actually, I can’t remember ever having used quite those words, but, as Brian Matthews well argues, memory plays tricks.

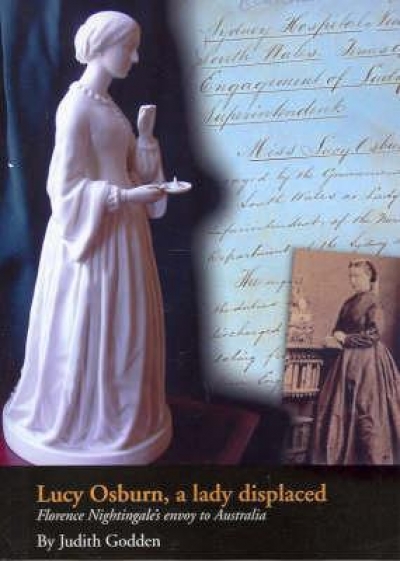

... (read more)Lucy Osburn, A Lady Displaced: Florence Nightingale's envoy to Australia by Judith Godden

by Beverley Kingston •