Theatre

Views From The Balcony: A Biography of Catherine Duncan by Michael Keane

by Desley Deacon •

John Gielgud: Matinee Idol to Movie Star by Jonathan Croall

by Brian McFarlane •

Finishing the Hat by Stephen Sondheim & Sondheim on Music by Mark Eden Horowitz

by Michael Morley •

Talking Theatre: Interviews with Theatre People by Richard Eyre

by Michael Morley •

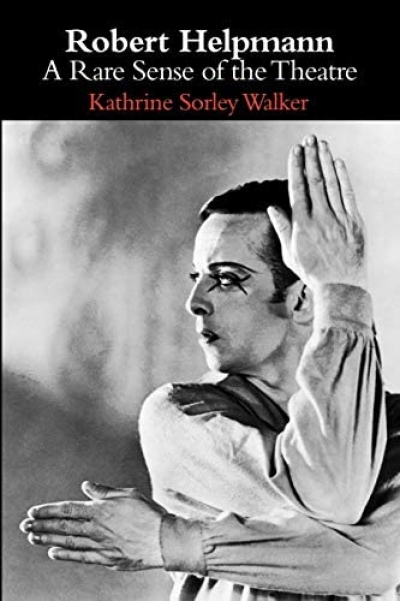

Robert Helpmann: A rare sense of the theatre by Kathrine Sorley Walker

by Lee Christofis •