Patrick McCaughey

Strange Country: Why Australian painting matters by Patrick McCaughey

The Rijksmuseum used to be the dullest of the major European collections. It looked as though Ursula Hoff had painted all the pictures. An air of dowdiness hung over the massive building and crowded collections where the good and the great indiscriminately mixed in with the mediocre in warren-like galleries with an over-supply of the decorative arts.

...In mid-May the Barnes Foundation opened at its new location in the cultural corridor of downtown Philadelphia. A cloud of controversy followed it to the end. The new building, handsome if flawed, from the gifted New York studio of Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, has attracted its share of criticism. The entrance, initially hard to find, is at the back of the building facing towards the car park and away from the parklands. The passage from entrance to galleries is awkward and inauspicious.

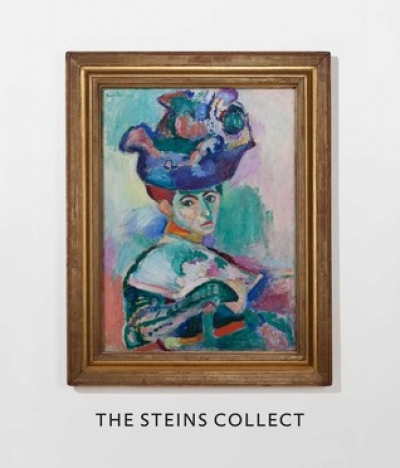

... (read more)The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde edited by Janet Bishop, Cécile Debray, and Rebecca Rabinow

The Donald Friend Diaries: Chronicles & Confessions of an Australian Artist edited by Ian Britain (foreword by Barry Humphries)

Paradoxical neglect

Dear Editor,

Patrick McCaughey’s article ‘NativeGrounds and Foreign Fields: The Paradoxical Neglect of Australian Art Abroad’ (June 2011) caught my attention because of its title, then its content. The ...