States of Poetry Victoria - Series Two

Series two of States of Poetry Victoria is edited by David McCooey and features poetry from Bella Li, Gig Ryan, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Brendan Ryan, and Lisa Gorton.

There’s plenty to crack onto, he says, a laundered Valkyrie stomps the DIY:

I reconstitute in the shed, my notes can hit the rafters,

no-one’s selfing over it, like upstairs

on their asbestos balustrade,

a tick-off at the slightest, though their kid

chatters and bounces on the planks.

At last summer rises on a blue cactus.

Without, it’s crumpled outside of time and dead.

I’m not the stonkered students, the pilled dancer,

the hail whomever, the arraigned owner,

not otherwise entitled, just the louvered kitchenette

or that and bin patrol that keeps you.

His in-law’s detrimental, or forgotten,

to home’s lathe and tack, a jail for your thoughts, and schemozzle.

Gig Ryan

Published in Have Your Chill (2017), edited by Pete Spence.

As her to you, unhurried,

pair formations addle a skyline,

extrovert welcoming traffic, selfless despot on the inner.

Even so, his pin-cushioned face glues to the backdrop’s nest of wombats.

The city changes from one skyscraper and slate

to the creek’s bag-junked ripple,

decisive formaldehyde splitting a cloud’s anagram of discontent,

replacing slouched velodrome with mouse-topped stove.

The introduced species pursue a spalling bridge.

No purpose other than as butter pat,

styled nuptials pick a branch.

Gig Ryan

Published in Have Your Chill (2017), edited by Pete Spence.

(Idyll II, Theocritus)

Where are my bay leaves and charms, my bowl with crimson flowers

while him inexorable

has gone from my bed like a dress

Distance: spells of fire wreathe you

Shine on this spin or grave

As sight stunned me

leaves burn

Wheel of brass turning from my door

Now wave is still and wind is still

My heart stopped in its foundry

As horses run, so we to it

Starts love’s knife

whose hair shone like dunes

whose body greased with labour

He had brought apples and his hair sprigged

unasked love into the oak and elm

and words went and came

Now from my lintels

Day drags from me and tells his flowers elsewhere

Farewell, ocean and its team,

whose white arms wrap

Silver flute who sang, and bright-faced moon

who knocks on a door of shadows

A rose for you, to match the wound

but tomorrow’s like now

Gig Ryan

You long for night to push away injunctions and sodalities,

sky’s hexagon clouds,

as veins lined with velvet straighten the road and undone casket

and morning’s birds click through dream.

Rest your eyes on the road like an inn,

bundled rubbish a corpse on the nature-strip.

You take the waters.

You embrace a door.

Snaked fields welter through molecules

as you burrow a dynamic exit.

Day tells you to circulate.

Royal blue flowers greet the neighbourhood’s ducks

and the palms-out front-yard grottoes,

but in the shells of Hades

or the mirrored corridors of Elysium

Castor and Pollux sing

Gig Ryan

have their own special nook nearby,

under that blackwood.

Why just there,

I ask myself: no particular foliage

has given a verbal meaning to the spot.

appears to murmur clan or family. Yes,

I know that sounds kind of patronizing,

but when these animals go through their routines

we can see a social order clear as day.

the milkwhite mother with joey in pouch,

moth-brown in hue, as are all

the rest of this little clan, one of them plainly

a mum too, with her teenager.

sleep beside Blanche under the darksome tree,

loitering there – if we don’t jerk into view. Then

suddenness sends them bounding off downhill,

except for the white one.

Yes, she’s at home.

a calming mother, white as vanilla snow.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

In memory of Graham Little

The forms in which I’m able:

Although invited, I‘ve declined

A pizza at that table

On the inert terrazzo.

I sit across the room, turning

Perhaps a little pazzo,

To a further funeral

In a verdure suburb; yet

I hardly knew at all

Whether they’re all alive.

Well, back I stay, to write in some

Benignly urban dive.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

hangs an off-grey trunk – odd word –

more than the puny dangling tail

marking this leatherjacket.

So much overcoat in our tropics, then?

But why is any creature as it is?

shipping creatures from those Turkish hills

before due discipline on deck. Sailing,

the very devil: not a Tasmanian one,

since that’s not in the book, those

bitter creatures dying in their south.

in some departed species upside-down

we are told. It’s not a fairy story.

Lumbering, munching, these can also gallop

and then the planet shakes like a dish of jelly.

Threatened jumbo touches all our lives.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

scratching their heads and hairy armpits.

So like them it was,

well, sort of

but ever so puny, while more or less rosepink.

Maybe the rich grasses and coconuts

had a kind of blessing to grant him;

nightshade and garlic somehow able

to shield him from the big cats’

ravenous prowling.

grow into, from this pipsqueak. But something

or other was in the balmy air.

not the merest monosyllable,

but alien shaggy spines

were kind of tingling there, like electricity.

didn’t want to attack this new thing

of unattractive flesh.

Perhaps you could feel

it was filled with

what they would come to call a magic spell,

harsh millennia later on.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

stared into from a cabin up above:

snowy cloud-sonata which then

recedes into softness

with its airy iceberg flocks

counterpoint, say, but can’t

feed serious fiction for

the yarnspinner has to eat

the heavy middle of our sandwich

Baghdad Prepares for Attack

to an ashtray smell or

puckered brocade on a chair.

Novels know everything

good, solid. While that white

cumulo-nimbus plays here

an almost sturdy part in

unpeeling our transience,

My sweetly musical

short fuse recedes again

into the shuffled stuff of dream,

no matter what rough beast

and blow the very legs

off our indolence.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe

Chris Wallace-Crabbe AM is the author of more than twenty collections of poetry. His most recent books of verse include The Universe Looks Down (2005), and Telling a Hawk from a Handsaw (2008). He is Professor Emeritus in Culture and Communication at Melbourne University. Also a public speaker and commentator on the visual arts, he specialises in ‘artists’ books’. Read It Again, a volume of critical essays, was published in 2005. Among other awards he has won the Dublin Prize for Arts and Sciences and the Christopher Brennan Award for Literature. His latest book is Rondo (2018).

Poems

'Demurely'

'At Table'

'Heidi-Ho'

'Creature'

'Nuages'

Were you with a girl at the footy?

my father asks while weighing down

on a milker. His large, freckled hand

like a stone on the claw of the machines

draining a back quarter of an old Jersey

reluctant to give. I lean against a post

darkened and polished by our shoulders.

No, I was just going for a walk. He looks

at me, adds, I saw you behind the trees.

My mouth begins to dry and my heart

picks up its beat. No, I was just going

for a walk, I repeat. He shakes his head,

turns back to the cow’s flank. I escape

into the holding yard, round up a flighty

heifer for the bail. When our eyes meet

I’m the first to look away.

One afternoon he drove me to Terang

to catch the Melbourne train. Early

and waiting, I was struggling to find

things to say. I looked to the red brick station,

the car park, the dashboard, the radio controls,

the heater, the automatic gear shift lever,

found myself muttering about the weather

while my father looked ahead and sighed.

A familiar, rising dread was catching in my breath.

I’ve got to go, I blurted, unbuckled my belt.

There was five minutes to spare. My father,

looking away, said, no, stay. We faltered

with our talk until a whistle could be heard.

I watched him drive away, slow

as any country father who has dutifully

waited for the train, waited for words

to come between the silences I am learning

to cultivate driving my daughters around

with their friends, accepting my role,

keeping quiet to avoid eye rolls, cutting looks.

Listening to their pauses and laughter

I think of my father – his silences

were paddocks that hadn’t been ploughed before

paddocks I’ve learnt to relax in.

Brendan Ryan

‘The things they carried were largely determined by necessity.’

Tim O’Brien

The beeping of horns, the relentless waves of scooters –

a whine that spirals to a high-pitched roar

scooting down alleys and footpaths

flowing like oil around taxis, through roundabouts

across bridges. Nobody has time for burnouts.

The sound of the streets is the growl of purpose

the 6 am momentum of fathers and sons

running errands through the veins of a city,

threading gaps between pedestrians

gliding over a history of patched roads.

The things a scooter carries – families,

teenagers texting, sacks of grain, a wardrobe,

two goats in a basket, a dead cow,

whatever’s necessary.

The things I carry – Tim Winton’s ideas of place,

my ignorance, my father’s need to be walking

out front, my Australian assumptions.

In a country with a history of invasions

there is no road rage, just polite chaos at roundabouts.

Rivers of scooters revving and scrambling round

our taxi until the momentum pauses

as if the roundabout was clearing its throat.

I’m cast adrift with a sticky shirt surrounded

by face masks, puffer jackets, and impassive faces

because white skin is pure, desirable as an iPhone

yet the fall-out from the American War lingers

with genetic disorders. A man with deformed limbs

drags himself across a busy road. Fathers

who fought with the Viet Cong pass their stories

onto sons who lead tours to jungle temples

while veterans wake up screaming at dawn

drink rice wine, beat their wives until

their granddaughters break the cycle

talking of abortions and teenagers

suiciding with unborn babies.

The elderly who survive sell lottery tickets from a gutter

while the faces of those who disappeared

we pay our admission price to at the War Remnants Museum.

The land is mined with stories, like the massacre

near Bến Tre nobody talks about

except those who are willed to keep returning

like choppers for the body bags. Each holiday

means facing up to spooky, the jungle smells

of things burning. Each morning a rooster crows.

A radio station broadcasts by loud speaker to the streets

what the government is doing.

Who is listening? Like heavy surf,

traffic pulsates below my window. I look down

to women sorting through hessian sacks

at a rubbish-sorting depot.

Other women fold their histories

into rice paper rolls, sit at markets

with a meat cleaver and a tray of raw chicken.

The men sit on low plastic stools watching

or laze in hammocks, scrolling.

The things a driver carries smoking on a river barge

as he steers a path between histories,

between the intimacy a woman creates washing

her hair in a Mekong tributary

and the weights a country asks its people to bear.

A baby’s face squashed against her mother’s chest.

The father driving without a helmet.

Their four year old son holding on.

His eyes stray to mine as the lights change.

I step out before the motorbikes.

Brendan Ryan

Cracks in the clay, locusts flittering over bleached stalks

old couches in the herringbone, ribbons of bird shit down the walls.

She married into the district, thin as a whisper

a woman who was summoned to the front rows at Mass.

Each day the wind passes, paddocks of rye grass sway.

She smiled through luncheons, gatherings

made the small talk that fertilised a district.

This year’s heifers watching from the shade of a sugar gum.

Like a rumour she slipped round her kitchen

school forms for children, his phone calls after tea.

Hoof prints shadowing a cattle trough

green algae choking the creek.

A hard doer, priests warmed to him talking a district,

a footy club, the cranky bugger who got things done.

Cypress tree shadows, muddy corner cut by the tanker

rusted car bonnets I rode down the mountain with her sons.

Nerves in her family, shadows beneath her eyes.

He bought up land, kept his neighbours at a distance.

Cow shit splattered driveway, sheets of corrugated iron

curling from a pigsty, capeweed encircling a dead calf.

A wife who dressed for his municipal heights, who toasted

his occasions, who stood on the edge of his name in the paper.

A man who couldn’t stop clearing his throat. Their children scattered

like birds that don’t know where to return.

They found her in the shower. The parting statement

of a farmer’s wife echoing round a district.

Brendan Ryan

In memory of Max Richards

Somehow you found the articles and poems

I needed to read.

Your key word searches driven by connection,

of passing it on.

Whether it be through the nodes of ADSL2

or the poetry of Heaney, Murray, or MacFarlane’s

nature writing,

whether you be in Doncaster or Seattle

or your shelves of books and manilla folders

at La Trobe,

you were always passing it on. Whatever

you found for me on the internet read as personal,

yet it was only after your death that I learned

I was one of the many, scattered across the globe,

who received the news and poems you set before us.

I sent you all I had written, for you were a first reader –

forgiving, close, a grammar stickler. Mostly

your feedback confirmed the work I had to do.

Sometimes poems were returned and broken up

into stanzas or quatrains giving form to my ramblings.

Your own poems arrived almost daily-

light, diary entries of dogs, trees, squirrels,

dream poems of other poets, the last outing

with your mother, the words of a father,

your tendency to be sombre yet playful about dying.

Your poems grew into a life from ‘an inarticulate

and non-self examining culture’. The moments

you left us, the urge for the next poem

may be all that a life writing poems can teach us.

There is no absence like the days following

an email of poems sent.

Trying not to wait for a reply

to see if a poem breathes or dies.

Your replies were never late, sometimes within hours.

The warm, confiding voice is still in my head.

Tall, gentle, Max who would rather exclaim

in wonderment than complain in negativity.

I was on holiday when I heard

you had been knocked down by a car,

your dog refusing to leave your side.

Some hours after my last email

some hours after I last thought of you,

the absence of its reply I am continually adjusting to.

Brendan Ryan

Lights over the rail yards are sparklers

that never die down. Every day

is a drug test day. All that’s left at Ford

is the security lights, shadows on the pedestrian overpass.

George Pell is refusing to leave Roma

where girls were once named after their fathers

who could, if so desired, sell them at fourteen

into slavery. George is cantankerous

as the music I listen to is old, out of date,

timeless. George is of a time that haunts

like a rash, of looking the other way,

of a justice that dare not be spoken of.

The brake lights of cars have become

pulses within my thoughts. Tim Buckley

launches into ‘Sweet Surrender’ – the epic

confession to bruised love I never tire of.

The shuttered weatherboards of Norlane

give way to the spindly trees of Corio

as empathy hardens like a row of bollards.

George pauses to compose before a camera,

to restate his innocence while families in Ballarat

attend funerals, not Mass. Flash of the golden arches,

lurid glare of a Caltex, George is immovable as The Sphinx

on Thompson Road, unforgiving as a red arrow.

I turn right into the darkness of School Road.

Brendan Ryan

Brendan Ryan grew up on a dairy farm at Panmure in Victoria. His poetry, reviews, and essays have been published in literary journals and newspapers. He has had poems published in The Best Australian Poems series (Black Inc). His second collection of poetry, A Paddock in his Head, was shortlisted for the 2008 ACT Poetry Prize. His most recent collection of poetry, Travelling Through the Family (Hunter Publishers), was published in 2012 and was shortlisted for the 2014 Victorian Premier’s Awards. He lives in Geelong, where he teaches English at a secondary college.

Poems

I remember you as you were, polished and dismissive

now sawdust and spangles lie on cedar.

‘Insufficient funds’ responds to my favoured transaction

at the checkout’s dystopia, a green-haired maenad slices the machine.

You saw in the eyes the future going away.

It carouses in the shadows

a watery silhouette of vengeance.

Mouth in ashes, words lie in air.

They trot off to a knobbly paradigm

while you manoeuvre the street,

another dickhead on a slab punishing childhood.

Grey object of consternation who could’ve etc., blither,

as past’s sorrowed turquoise eyes cream distance.

Melodrama thickens in a showroom and a cap of tin.

Outside, cars parley and stars replace attrition.

Embrace the true world shoved in a treetop

and the particulate rainbow mugging the horizon.

There lies the repentant wafer

or the two-timing retreads of yesteryear.

Gig Ryan

Published in Read On (2018) edited by Pete Spence.

Gig Ryan’s last book was New and Selected Poems (Giramondo, 2011), published in the United Kingdom as Selected Poems (Bloodaxe, 2012). Manners of an Astronaut (Hale & Iremonger, 1984) was re-issued by Shearsman Books, UK, in 2018. She was Poetry Editor of The Age from 1998 to 2016. Her work first appeared in ABR in 2001 when it began publishing new poetry. She lives in Melbourne.

Poems:

'Simaetha'

'Grotto'

'Principle of Insufficient Reason' (Read On, ed. Pete Spence, 2018)

'Know Your Product' (Have Your Chill, ed. Pete Spence, 2017)

'Rented Features' (Have Your Chill, ed.Pete Spence, 2017)

First

That I have written, of places I have not been. To Carthage I came, where there sang around me in my ears a cauldron of unholy loves. And in the vast courts of memory, the caverns of the mind. I have heard great waves upon the shore, I have remembered what it is. In other ears: the scaling of heights. These circuits of stars, compass and pass by.

Second

That what I have seen I have seen from houses. That in my father’s house was a strange unhappiness. That I had searched for it, in my life, in the hollows of doors, that I had found it, that it had found in my home. And in my home I had neither rest nor counsel. The days, the soul of man riveted upon sorrows; now and then the shadow of a woman, in the far corners of the house.

Third

That I walked, under the trees on the boulevards, in a mysterious darkness. Through the stone city, these streets I have seen only from houses. Towards darkness I have dared. In the provinces, under the fall of leaves, and the dream moved me more than the dream itself.

Fourth

That I have been foolish. That I have loved, and Thou in me, Thou also. That I have loved not yet, having loved those that must die. Forgetting the friendship of perishable things. So in acts of violence – iniquity. As if she had appeared in the room; this place to which she would never come. While the days darkened and an ill wind stirred. I walked the streets, my heart, as if seized. I could not. I could no longer think of anything else.

Fifth

That when the time came – remembering distinctly the afternoon: I was then some six or seven and twenty years old, reading those volumes, revolving within me corporeal fictions. I had broken this view often, into its corporeal fictions. That day, in the afternoon, I had sat beneath the frame of the door, with the view, with those volumes, six or seven or twenty. I had wept, against the frame, I had read – I had in the afternoon asked: heal Thou all my bones.

Sixth

There are sounds I do not hear. Sometimes, at the edge of water and surrounded by trees.

Seventh

That I would grow old. At the entrance to the avenue of oaks, in those meadows, before the ponds. Foretelling, in great detail and with gravity, transits of the luminaries. And out of them, my hope from my youth: in what year and month of the year, and what day of the month, and what hour of the day, and what part of its light.

Eighth

That the entire forest was plunged as though under a sea. As at the beginning of the world, as if there were only the two. So was I speaking, when – with a more premeditated return, with more precision, as though upon a crystal glass – I asked my soul, why she was so. Over the forest did my heart then range. I shut the book. And I cannot say from which country, which time, I cannot say from which it came.

Ninth

That at the end I do not recollect if I am what I say. That I was grieved. And whatever I beheld was death.

Tenth

Eleventh

Twelfth

Thirteenth

Bella Li

Notes

Phrases were sourced from the following texts: Marcel Proust, The Way by Swann’s, translated by Lydia Davis (London: Penguin Books, 2002); The Confessions of Saint Augustine, translated by Edward Bouverie Pusey (London: John Henry Parker, 1838).

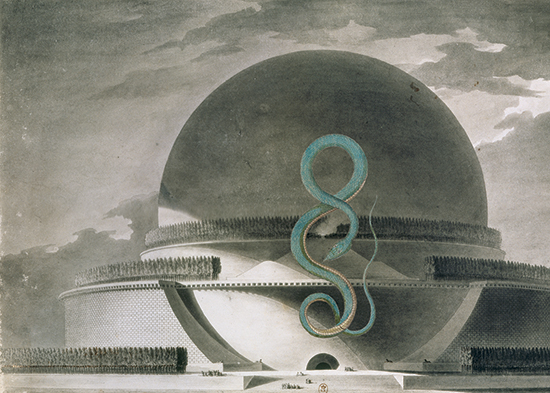

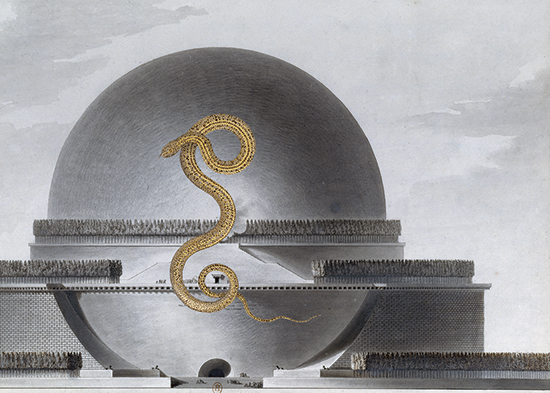

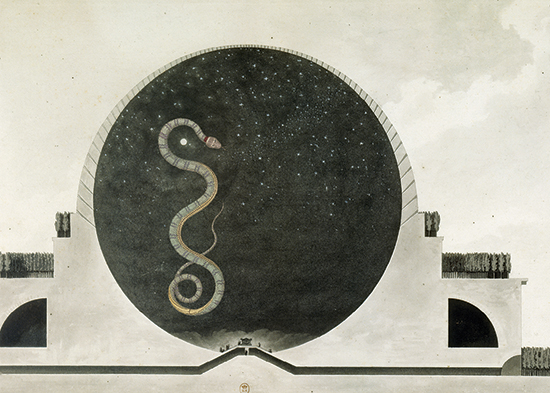

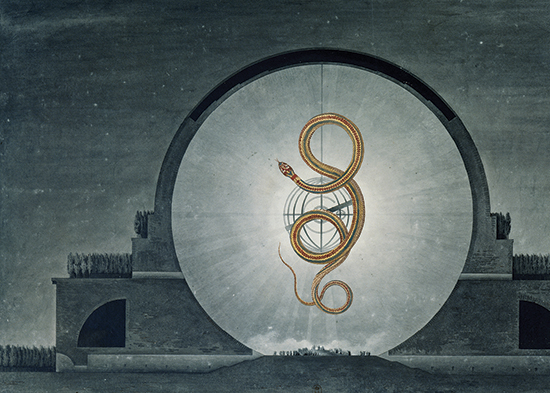

Images for collages were sourced from the following texts: Albertus Seba, Cabinet of Natural Curiosities (1734–1765; Den Haag, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Shelf 394 B 26-29); Étienne-Louis Boullée, Cénotaphe de Newton (1785; National Library of France).

Bella Li is the author of Argosy (Vagabond Press, 2017), which was commended in the 2017 Wesley Michel Wright Prize, highly commended in the 2017 Anne Elder Award, and won the 2018 Victorian Premier's Literary Award for Poetry and the 2018 Kenneth Slessor Prize. Her work has been published in a range of journals and anthologies, including Best Australian Poems and The Kenyon Review, and displayed at the National Gallery of Victoria's Triennial . Her latest book is Lost Lake (Vagabond Press, 2018).

Poem

– if that indeed can be called composition –

wrote Coleridge –

in which the images rose up before him as things –

‘In the summer of the year – the Author, then in ill health, had

retired to a lonely farmhouse – ’

where, seated in his illeism by a window, the Author passed

into the background of his imagery –

woods, clouds hanging over the sea

in deeps of glass – ‘sole eye of all that world’, or

vanishing point it

floods back through – ‘huge fragments vaulted’ –

‘You must know that it is the greatest palace that ever was’ –

its rooms like clouds

following one another in an order hard to memorise – ‘all gilt & painted

with figures of men & beasts & birds’ – its hall of statues –

stopped machines –

leading away and back into that first astonishment – its green smell

like the cry of a bird

A city at first light, long-shadowed streets –

An open plain of rubbish behind rails –

A sky afloat inside its landscape – clouds in the river,

wind in the dry mouths of the grass –

beating images

from their dark wings

quick shadows brightening –

‘So twice five miles’ – ‘So twice six miles of fertile ground

with Walls and Towers were compass’d round’ – ‘were girdled’ –

‘In Xamdu did Cublai Can’

ride out on his white horse

with a jaguar on its pommel, loosed

to hunt the animals stored

in the wide cage of his pleasure –

‘a stag, or goat, or fallow deer’ –

carcasses for his gyrfalcons in their mews –

A is for Alph – sacred river of

converging perspectival lines –

Momently it rises – momently

sinks back – into that lifeless ocean

the letter’s two struts stand

afloat on, raising its tower again –

– A woman crying in her wilderness

– A woman singing

– A ‘palace so devised that it can be taken down

and put up again

wheresoever the Emperor may command – ’

From far off, the Emperor hears his dead

in panoply of ice

speaking war through their long smiles –

‘And now once more / The pool becomes a mirror’ –

His poem is a mirror made of metal –

its one face the engraving of a landscape –

the other, polished to brightness,

keeps taking things into itself

and letting them go – A palace of images

that the Emperor walks about in –

its dome of air, its caves of ice,

in the flashing eye of a mirror, his floating hair –

‘The author continued about three hours in his chair’ –

The Author walked in

through the iron gate of its palace – Only

his shadow moved among the shadows –

He was in its hall of statues

when a sound of rain

opened like a door into that room where he slept as a child

and all night it rained, all night dark

poured onto its glass like rain –

‘Irrecoverable – ’ meaning, it couldn’t be finished –

Circumstantial as a preface, things rising up

out of their images before him –

or ‘sunless sea’ –

Midway, the shadow floats – long-dead Emperor

with a voice of water, looking out

from mirrors with a face of false calm –

The Author watched his Person of Business

walking in from Porlock

among deep fields of grass – His hat like a stone

skimmed the tips of the seedheads, late-

summer pale, scattering

from the wind like light on water – and

elderflowers, poppies, speedwell, hyacinths –

‘I have annexed a fragment – ’

Lisa Gorton

– is made of windows

side by side and repeating the way two mirrors

face to face cut halls of light

back through their emptiness – Its façade,

like that version of desire which

feeds on absence, endlessly draws in sky –

Clouds sunk in glass advance

across its fret of cast-iron columns, incorporating it

in pale brightness till at its edge

they pour off vanishing – An hallucination

industry caught up with – plate-glass set

facet by facet into its vault of light –

‘It is, above everything, the science

of beauty’, wrote Mr Paxton, copying out in

upright iron the radiating rib and

cross-rib growth-pattern of veins

underpinning the leaf of that astonishing water lily

original to the bays and still waters

of the Amazon and its tributaries –

a leaf and flower of which, preserved in spirits,

John Company’s unworldly botanist Mr Spruce,

under contract to steal the means

of producing quinine – six-hundred plants,

a hundred-thousand seeds of the Chincona forests

of Western Chimborazo – sent back, remarking

how its leaf, ‘turned up, suggests some strange

fabric of cast iron’ – brought to flower at last

in an alien season inside a glass-house

replicating in large the infrastructure of its veins –

They named it Victoria Regia, whose ‘dearly beloved consort’

commanded this inventory of an Empire

or hoard of wreckage closed in glass –

Uncovered ground, bare-iron pillars,

a confused pile of scaffoldings – At its centre

the skeleton of its great transept arch –

then columns, then girders spanned across

its naked distances and hanging bays of glass

inventing aisles with staircases

to second-storey galleries inclosing even

its elms, as still as reproductions,

and sparrows nesting in their leaves –

Its crystal fountain is glass and elaborates itself

up through complications of fluted column

and lily-flower-shaped cup to where water

pours back from the idea of water –

Mr Paxton thought to set the floorboards

an half-inch apart so the women’s skirts

could sweep the floor clean as they passed –

Overhead clouds, like images

in the mind of a reader, replace themselves

time and again against its glass –

A steam engine dragged in by sixteen horses,

a column of coal from Newcastle,

sixteen-tonne weight, the crane that raised

the suspension bridge at Bangor, the iron ore

and the Sheffield blades, the elephant’s tusk

and Indian carvings in ivory, classic marbles of Paros

and Hiram Power’s Greek Slave, the cotton mills

and cloths of finest texture, tail of a wolf

and soft fine fur of the badger, plumes

of the ostrich and raiments of the camel’s hair,

antique silks as heavy as armour, armour

of close-worked chain, a battle-axe finely

inlaid with silver, Winchester’s patented revolving

turret rifles, an ormolu clock that runs for a year,

the Koh-i-noor or ‘mountain of light’

inside an iron cage, and Bontem’s prize-winning

automaton humming-birds that in their glass-

shades flit from branch to branch, opening

their wings and beaks of gold, and sing –

The Iron Duke had his answer to the question of the nesting sparrows.

‘Sparrow-hawks, Ma’am.’

Lisa Gorton

This poems ‘The Crystal Palace’ and ‘Mirror, Palace’ include phrases and descriptions from John Tallis, Tallis’s History and Description of the Crystal Palace and the Exhibition of the World’s Industry in 1851 illustrated with beautiful Steel Engravings from Original Drawings and Daguerreotypes by Beard, Myall, etc. etc. (John Tallis and Co., New York and London); from John Fisk Allen, Victoria Regia, or the Great Water Lily of America with a Brief Account of its Discovery and Introduction into Cultivation: with Illustrations by William Sharp from Specimens Grown at Salem, Massachusetts, U.S.A (Dutton and Wentworth, 1854); from Leigh Hunt’s Journal: A Miscellany for the Cultivation of the Memorable, the Progressive and the Beautiful, No 1. December 7, 1850 (no 17, March 29, 1851); from the Book of Ser Marco Polo: The Venetian Concerning Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, translated and edited by Col. Sir Henry Yule (London: John Murray, 1903); and phrases adapted from the Ivory Tablets of the Crow in the Art of the Ninzuwu (online); as well as from Coleridge’s Kubla Khan; Or, A Vision in a Dream, A Fragment.

Stone eidolon at the end of a walled-in colonnade –

She was born from the sea, light

off the foam of the sea –

[Alex]andros son of [M]enides

citizen of [Ant]ioch at Meander

made [this] –

Her body rises over the crowd – She looks aside

as though at something about to happen –

Stone in the flesh, her blank eyes

invent distances – Stone comb marks in her hair –

Her hair, unloosed,

enters into the heraldry of women’s gestures –

Under her right breast a hole

where the metal strut held up her arm –

In her left hand she held an apple –

Light sinks an inch deep into Parian marble –

The sculptor of marble is a sculptor of shadows –

Nude upper body and base of drapery –

two blocks of Parian marble joined under its first fold –

Drapery falls from her thighs

like folds in water –

like dense-packed snow

the quarry on Paros where slaves cut blocks out of the mountain,

dragged them on a road lined with marble down to the ships –

A farmer found the torso buried in a wall –

A wall of cut stone

floored with rubble,

the torso lying on its side half-sunk in dirt –

The robes she dressed in to seduce Anchises

outshone fire – shining necklaces on her soft throat,

golden earrings in the shape of flowers –

Her arms are buried under the landslide –

Where her arms are broken the surface is like torn paper –

A path steep downhill clutching at branches, grey-green olive trees,

grey leaves whitening from the whipped-back branch –

A soldier paid the man to keep on digging –

They stood her in a field –

Stone heaps and broken columns, salt-pale grass –

They broke her arms off when they dragged her out –

In her left hand she held a mirror –

They smashed her earlobes to get the earrings off –

The ambassador arrived to find men loading her onto a ship –

The marble is scratched

where they dragged her over the rocks –

They have searched the sea there for her broken arms –

The dragoman had the men whipped

who sold her to the ambassador – After the war broke out

the dragoman’s body hanging three days in the street –

The ambassador gave the statue to his king –

Her arms lie in a heap of broken marble in a warehouse,

hands holding out the things that tell her name –

The mirror she holds is a polished shield –

On the side she turns towards us, painted gold,

a warrior runs from the burning city,

his father clinging to his back, son crying behind –

the sky, though made of gold, looks dark with smoke –

The statue looks into its other side

in which there is not one thing more real than another –

rank after rank of light between the mirror and its eyes –

Lisa Gorton

Storm water piped under the cutting comes out here,

unfolding down under the surface of itself, bluish oil-haze

clotted with seeds and insects – where down the gully

dank onion weed tracks the secret paths of water – Late winter,

black cockatoos scrap and cry in the Monterey pines

which bank the gully’s side – The water flows to a standing pool

out the back of the CSL where a metal trap stops leaf-litter and bottles

and the massed reeds are that washed-out grey

which shines at dusk – From the wetlands water is pumped

up to the golf course or sometimes floods the creek, now a concrete drain

beside the motorway into the city – Across the gully

the factory generator begins itself repeatedly – Behind the cyclone fencing

its rooves stack the horizon – Smoke from its furnaces, widening out

through shadow like scratching on a lens glass, is suddenly there,

lit coils across the brick wall of the factory, blank updraft swarming

in and out of light that whitening shiver out the back

of magic lantern slides, invented depths giving its close scenes place –

The rain is first a screen that folds in on itself its

infinity of repetitions, nerve-end flares, and then the leafless furze,

its each thorn strung with unrefracted rain, is the infrastructure of a cloud

stopped on the gully’s side and at each step vacancy

scatters out of the pale tops of the grasses, untellable, singular, immune –

Lisa Gorton

A single cloud now climbing the hill towards me

and the blue-grey shadows in it are in the shape of a fire

and all about it brightness where the light pours through –

Uninterrupted its shadow moves over the craving grasses –

pale seedheads now shaking out light – as with a sound of wings

the scrubwrens scatter out of head-high rubble

overrun with weeds – tussock, milk-thistle, dry stalks of fennel

in its wind storm ratcheting – instant and abyss – how all this

pours through the front of now into that self-lit scene persisting

out the back of all description – Here where the cloud

rebuilds itself like a room in a mirror – silent, foreshortened, safe –

and loses nothing, being composed of gestures – A cloud

which even now is flooding in one unbroken wave

back through the gulfs of light – This room in which the artist sits

making a cloud of ink and charcoal, smearing the page with shadows

to liberate the absence that is there – Like light through cloud

it feeds itself through her, the skin of her hand, white ink of the page

and newspapers spread out across the table, battening over the hospital

and the children’s prison – Numb, ignorant rain falling from it

without sound now the way it falls through mirrors in

light-like lines closing a room in glass – She cuts the page in strips,

pins them to a wall, would have them stained with hands –

Lisa Gorton

Now on its stone heaps the tussock is dry

stalks the colour of a scratch in glass and rattling fennel

tendrils from the root – Along the cutting’s side

speargrass with a rain wind in it moves through the shape

of a catching fire – At the level of my eye, its

close horizon, grasses moving many ways

like shivers, incandescent, each force forwards

through itself into the front of light, its

single instant the field falls through perpetually –

This grey light before rain in which years

I have forgotten invent a landscape still

in what I have named landscape – ruinable,

see-through, piece by piece drawn into that blank

in thought which sets the names in their array –

tussock, speargrass, wild fennel – bright charges

hung upon abyss – Do you remember?

In head-high grass, its pale seedheads, the wind is

massing light, lights moving in place and scattering down –

the grass untidy, touchable, steeply its slant

stalks narrowing back into their likeness –

where I am going in through leaf-clatter, corner branches

out to where, between the privet and the green palings,

a space is opening the way a fire is loosed

out of the dry branch into its own existence

and does not know me, walled in itself, its

dazzling blank – The road will come through here –

Lisa Gorton

Lisa Gorton, who lives in Melbourne, is a poet, novelist, and critic, and a former Poetry Editor of ABR. She studied at the Universities of Melbourne and Oxford. A Rhodes Scholar, she completed a Masters in Renaissance Literature and a Doctorate on John Donne at Oxford University, and was awarded the John Donne Society Award for Distinguished Publication in Donne Studies. Her first poetry collection, Press Release (2007), won the Victorian Premier’s Prize for Poetry. She has also been awarded the Vincent Buckley Poetry Prize. A second poetry collection followed in 2013: Hotel Hyperion (also Giramondo). Lisa has also written a children’s novel, Cloudland (2008). Her novel The Life of Houses (2015) shared the 2016 Prime Minister’s Award for fiction. She is the editor of The Best Australian Poems 2013 (Black Inc.).

Poems

In an age when the news is relentlessly bad, it is tempting to think that we can turn to poetry as either a flight from the pathological politics of our time, or a higher commentary on it. As the poets in this year’s Victorian States of Poetry Anthology show, poetry’s relationship with the news of the day is more complex than that.

Chris Wallace-Crabbe, now in his mid eighties, continues his (thankfully long) ‘late period’, with work that takes in both the long view and the intensity of the here and now. This work is concerned with a form of lyricism, but one in which dreams are prey to some harsher reality, some ‘rough beast’ that will arrive ‘to trash our ghosts / and blow the very legs / off our indolence’. Poems such as ‘Creature’ and ‘Heidi-Ho’ show Wallace-Crabbe’s tragi-comic vision is especially important for the troubled times in which we live. Now that ageism is finally becoming as unacceptable as the other isms, Wallace-Crabbe’s poems powerfully show us the importance of attending to elder voices.

Gig Ryan, in her different way, is also concerned with collapsing the historical and the contemporary. Ryan’s poems are more obviously elliptical in their expression, but they are no less powerful for that. By bringing together the abstracted world of Greek myth with the suburban imaginary (‘bundled rubbish a corpse on the nature-strip’), Ryan makes our world all the stranger. If the uncanny is the disquieting interplay between the familiar and the unfamiliar, Ryan is master of an uncanny poetics, one in which the ‘melodrama’ of psychology and sociology is played out in an inimitable idiolect.

Brendan Ryan is deeply concerned with the contemporary world, especially the bucolic setting in which he grew up, but he too makes the apparently familiar impressively strange. But as ‘Driving to Debating’ shows, Ryan’s imagistic aesthetic can also both deal with the bad news of the day, and see its long perspective:

George Pell is refusing to leave Roma

where girls were once named after their fathers

who could, if so desired, sell them at fourteen

into slavery.

Ryan’s poetry commands our attention because it is often affecting, but also because it works the real into our most important abstractions, such as ‘a justice that dare not be spoken of’.

In the three poems by Lisa Gorton, we see an extraordinary attention to detail, to the weight of the real, and to language as an act of style. When Gorton quotes a Victorian – in the temporal rather than geographical sense – definition of botany as ‘the science of beauty’, she could be talking about her own work, which is both considered and mysterious, exacting and playful. What makes Gorton’s recent work all the more commanding is the way it uses the historical record itself as a source of the uncanny, and a source of understanding ourselves.

Bella Li’s sequence, ‘Confessions’, with its profound use of the visual, also shows how the historical record can be refashioned. ‘Confessions’, another project concerned with uncanny effects, remixes the highly stylised language of confession (from Augustine to Proust) with the visual language of the eighteenth-century natural historian Albertus Seba and Étienne-Louis Boullée’s monumental designs for his proposed cenotaph to honour Sir Isaac Newton. In doing so, she seems to seek a wholly new language for what we recognise as poetry.

In the previous States of Poetry anthology that I edited, I wrote in my introduction that I focused on work ‘attracted to openness, energy, catholic interest, and wit.’ I stand by that description for this year’s anthology, but this year I am also struck by how each of the poets demands attention because of his or her style. Such stylisation is evidence of an act of intense attention, and to seeing the poem as something intensely wrought. In the age of fake – as well as bad – news, this too can be a political act. Paradoxically, the very factitiousness of the poem makes it the genuine article.