States of Poetry South Australia - Series Two

Series Two of the South Australian States of Poetry anthology is edited by Peter Goldsworthy and features poems by Steve Brock, Cath Kenneally, Jules Leigh Koch, Louise Nicholas, Jan Owen, and Dominic Symes. Read Peter Goldsworthy's introduction to the anthology here.

the priests and the witchdoctors both

will bless your new vehicle; the Virgin

will keep you in mind if you fashion a model

of what you want, attach it to the front of the car

a second storey on your house

a house pure and simple

a swinging baby doll

attached to your grille

‘The Virgin won’t give them anything’

shrugs Father Abraham: it’ll be hard work

gets the second storey or the first

good luck or bad that delivers or

witholds babies

The medicine men pooh-pooh the minimal

offices of the Friars - they themselves offer

in addition to the basic plan, prayers to the earth gods

thrilling rituals and holy smoke

the camera pans round a wall of wax engravings

for the attention of the Virgin of Copacabana

here, our gurus advise visualising

what we desire:

a private welter of wants

I like the Bolivian way

heart on your sleeve, swinging dice

buffeting the rearvision mirror

a decade of the rosary, a burnt offering

hey! down here! we’ll take anything!

a shout-out to whoever’s online

Back at Cranfield Street by 5

Motorway horridness receding into fumey oblivion

We are just in time for Pointless – words ending in ‘air’

‘debonair’ ? – others, phoned at random, knew that one

Two pounds fifty left on my Oyster card once I’ve put it through the barrier at

the delicate, high-slung, white and black, wooden pedestrian bridge over the

Brockley line

all along the route is densely wooded with lanky elder saplings

dock and nettles, layers of green petticoats below the asphalt belt

Wendy’s raspberries are flourishing in her damp back garden

I only notice the hundreds of orb spiders strung on webs between the bushes

when I come eye to eye with one as I bend to gather fruit

Brockley Market turns two on Saturday: I’ll be there.

travel the best excuse to scavenge: any find might be a clue

to the answer you’ve been seeking

I’ve picked up a copy of Worzel Gummidge

‘Do tell us how you came alive?’

‘... so far as I can mind, it all started with a itching in the head,

when the turnip began to sprout.’

Three Oxford Children’s Modern Classic authors

ring bells, from the list inside Worzel’s cover

Rosemary Sutcliff, Philippa Pearce, Astrid Lindgren

I know the TV Gummidge, not the book

or its author, Barbara Euphan Todd

who ‘started writing when she was eight’, the little swot

the written story’s charm eludes me

a grim, mirthless tale of mud, muddle and mayhem

Why do I love England? And yet I do.

banded bumble bees already at work

by 6 am in the rosemary

slaters still hovercrafting over the bathroom floor

not realising the sun’s up

not a shrug of wind in the garden

the surface of the sea

taut-stretched grey marle

yesterday, the pair of sea eagles

flew above the car, keeping pace

for a bit as I drove

an escort of black-and-whites

on your way, ma’am

nothing to see here

Fed Wendy’s cat, walked to Broadway

Market through London Fields

a month from now these will be

once again names to conjure with

jump on a 236

Newington Green

lured by the memory

of Belle Epoque patisserie

glowing golden in a corner

always misremembered

as Raisin D’Etre

My fellow-travellers clearly

locals despite farflung origins

even on my ninth visit

I’m a day-lily among annuals

When I’m seated at my table

the escargot pastry is perfect

the coffee not

c’est la vie

From Wendy’s bookshelf

I’ve taken Death of a Ghost

Margery Allingham

best-loved Dame of Crime

died a year younger

than my present age

so many books!

beneath an unflattering

photo, her Green Penguin blurb

‘In my family, it would have

seemed strange not to write’

yet I know no other Allingham

my internal satnav (not the Epoque

vendeuse’s doubtful directions) tells me

Church Street is nearby

Abney Park cemetery therefore

in walking distance, a favorite for

the unchecked frivolity

of its riot of nameless

creepers and saplings

gobbling tumbled memorials

rampaging madly on

my lately-penned Will specifies

eco-burial, probably in a polite park

better this rampant decay under

thrusting, immodest new growth

the Victorian way

en route to last things, I detour

via penultimate ones

a light-filled ex-factory

scuffed wooden floors

raised platform at the back

sparse, select items dangling at intervals

and in the wide window

a light-as-air linen swingcoat

faintest oyster blue-grey

made for a small man my size

not too many pounds asked,

enthuse with the attendant

who seems as charmed as I

by the garment, as perhaps she is

leave empty-handed

In the cemetery I peer through a screen of oak leaves

squint at the flat Yuri had, with Teresa the mad landlady

a few years back, overlooking this tangle of rubble

deepest green shade

the passage of years

sickeningly vertiginous

when it’s your childrens’ years

you’re reckoning, let alone

amongst tombstones

outside Epoque earlier,

two girl cyclists hugged goodbye

stalwart in Birkenstocks,

tortoise-shelled by Freitag backpacks

full of calm and poise

grounded as I wasn’t

I thought of my reading at their age

how I longed for each new

Drabble, bound to be bursting

with important

tips for living my modern life

all forgotten

Margaret is coming

to Writers Week, I’m reading

her new books, elderly heroes

all passion spent

Margery’s spectral tale from 1934,

in my backpack, is a painter’s story

Lafcardio, RA

Royal Academician

my ghosts today are clamorous

not unfriendly

a tablescape

drooping roses near death in a jam jar

dull Ian Rankin in a yellow cover lying upside down

Mongolian phrasebook

sample tube of Sensodyne

Cinema ticket: The Great Beauty

opener for the Italian Film Festival

password to Smartygrants

for accessing two hundred applications

business card for Phnom Penh silver and gemstone jeweller

a blue and a black biro

invitation to popup arthouse fundraiser at Goodwood School

receipt for Geranium Leaf Aēsop cleanser

Yuri’s business card at the Apple Store

with the bitten silver apple on gloss white

white enamel teapot with red-rimmed lid

remote control for Smart TV

another Scottish crimemeister, Stuart McBride

Close to the Bone, his back to me

at the far end of the table

notebook

this pen

Cath Kenneally is an Adelaide poet and novelist whose book Around Here (Wakefield Press, 2002) won the John Bray National Poetry Prize. Of her six volumes of poetry, the latest is eaten cold (Walleah Press, 2013), in which each poem responds to one in the volume Cold Snack (AUP) by Auckland poet Janet Charman. Kenneally’s two novels are Room Temperature and Jetty Road (both Wakefield Press). She works as a print and broadcast arts journalist, being Arts Producer at Radio Adelaide for many years and responsible for Writers Radio, an award-winning national community radio books and writing program. She was the inaugural CAL/J.M. Coetzee Writing Fellow at the Coetzee Centre at Adelaide University in 2016. She holds an MA and PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Adelaide. Her work has appeared in many national and international journals and anthologies, and been translated into several languages.

Cath Kenneally is an Adelaide poet and novelist whose book Around Here (Wakefield Press, 2002) won the John Bray National Poetry Prize. Of her six volumes of poetry, the latest is eaten cold (Walleah Press, 2013), in which each poem responds to one in the volume Cold Snack (AUP) by Auckland poet Janet Charman. Kenneally’s two novels are Room Temperature and Jetty Road (both Wakefield Press). She works as a print and broadcast arts journalist, being Arts Producer at Radio Adelaide for many years and responsible for Writers Radio, an award-winning national community radio books and writing program. She was the inaugural CAL/J.M. Coetzee Writing Fellow at the Coetzee Centre at Adelaide University in 2016. She holds an MA and PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Adelaide. Her work has appeared in many national and international journals and anthologies, and been translated into several languages.

Poems

in my end is my beginning – just

a rat’s nest coiled in back-shed dust,

a tangle of demented knots

gothic as the Grimms’ dark plots,

a thrumming song of wreak and wreck

(whose satin bed, whose trusting neck?),

the tautened threat from fist to fist,

the carpe diem tug and twist.

My image haunts your DNA,

that tiny ruthless shadow play.

I’m hairshirt-hallowed, gallows shred,

bog-buried hair and voodoo thread,

discord from a black mass choir,

devil’s helix / heaven’s tripwire.

My dreams are rope, I nightly string

up rank despair, the summer swing

to grace the judas tree’s green spread.

Crumble up your holy bread

and feed the crows spaced out along

my cousin wire who codes this song.

This came out of a workshop exercise, a version of Kim’s game – translating objects on a tray: pebble, spoon, nut, string, thimble etc. JJO

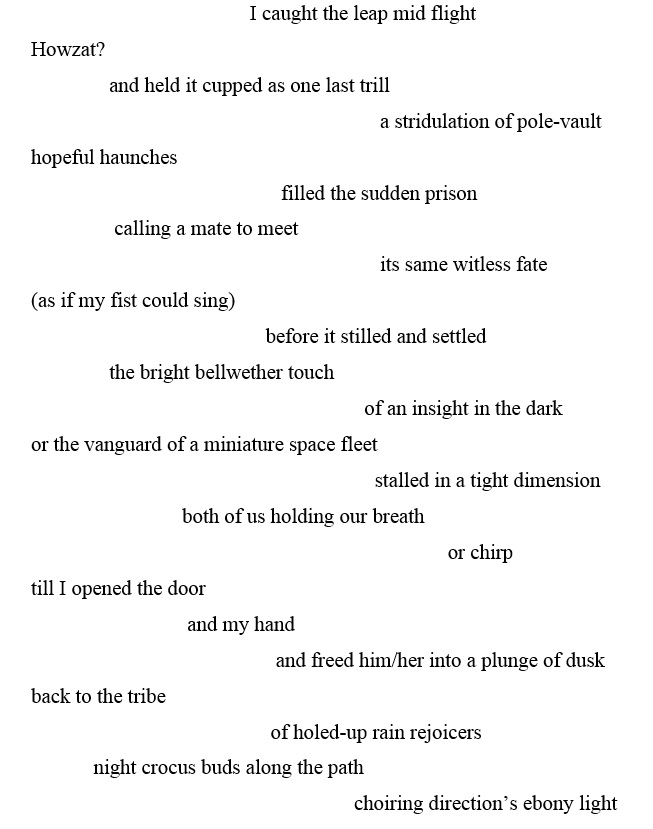

Insects are nature’s netsukes, and, by jiminy, crickets are such bright creatures. JJO

This ‘structural scandal’, tongue’s yen for kin

as family is a sort of chime, the thrift

of loaves and fishes unconsumed by scorn,

is natural as natural history

with all its modulations of again –

seed, crystal, comet, crocus, rain.

Even our code’s in rhyme – adenine,

cytosine, guanine and thymine – turn

and turn again (cynghanedd rules the cells).

Call cousin metaphor a silent rhyme,

flashy matchmaker signing What a catch,

this link and latch of things.

Say reason follows suit when politics spells peace.

Note In the beginning was the Word and it rhymed:

quark, antiquark, spin, counterspin.

Left and right are the first and best of gifts;

hand clap, bird flight. Born binary,

we lose and use our balance stepping out,

or, for embodiment of rhyme in tights on a roll,

ape Clem on his circus wire with music and meaning

weighting the opposite ends of the balancing pole.

Remember when first couplets of smile-frown

made enemy-friends with knee scabs for paired badges

as right played tag with wrong and gang was the full stanza?

And how sound conjures friend from stranger

– song belong song, half riff or exact pact,

sun moon one tune, a double cadenza,

with any word an aria centre stage

through (cymbals, please!) full frontal rhyme,

that glitzy tenor of derring-do. Soprano, too.

Irresistible, these prophets of philander,

intuition’s viceroys, double agents all:

Apollo tipsy, Dionysus in tails.

How they’ll subvert a poet and serve a clown!

Their Mercury conjunct Uranus warns

it’s no go the status quo, no go the Fall,

so if you want the moment’s CPR,

the breath and beat of second chance – yes no? –

rhyme’s team will clinch the deal.

The first line quote is from Roland Barthes’ ‘rhyme is a structural scandal’. I like rhyme’s tensile strength, its echo of the pattern of things, the way it can surprise and validate, and sometimes usefully influence a poem’s narrative. JJO.

after the painting by Jan Vermeer

Two strands of pearls, warm cream, cool blue,

are spilling over a coffer and onto

a crumple of ultramarine against a wall

below a yellow curtain shifting the muted light.

Four gold coins and a silver ducat

wait to be weighed along the table edge,

but the sidelong mirror’s narrow sliver can find

no avarice in its harvest, this calm face:

the soft mouth and downcast eyes are

tender for the scruples of the world.

Her raised right hand is testing the miniature scales,

her left hand’s at the vanishing point,

and on the wall behind, a sprawled Last Judgement

murkily segregates saved from damned.

This seems no cautionary vanitas –

there is nothing in the balance here

but the commerce of light and air;

emptiness equals emptiness in the level pans

the way our moment is aligned with hers:

the chaffer of maids, the scritch of a broom in the hall,

the downstairs tap and squabble and thud

of Klaus repairing a boot, Nienke haggling for cod,

and next-door’s boys at quoits in the lane.

This small room stood when a single spark

sent the Arsenal up ten years before,

along with the whole Second Quarter of Delft;

the immense shudder of sound hit Haarlem.

Death slips easily into a town, a poem.

Jan Vermeer has framed it out of a scene

where time keeps testing true.

One of a series of poems on the paintings of the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Jan Vermeer of Delft. JJO.

Heaved up or fountained down, the wooden slats breathe a shirr

and clattered repeat of the mill of their making, a satisfactory thud

like the outcome of a stock plot. Half hoist, they hang askew with a

pained smile, and bell pulls for self-service which pirouette

to a glut of knots. Tilt by tilt they’ll orchestrate your day, underlining gloom

and overruling light. Or clapped full shut on the heat, let laddered thread holes

shimmy the sun down beaded falls of bright. Late afternoons, the whole blank

bamboo book concertinas up to bare the view as the scooped weight

calligraphs its lines of cord – left, middle, right – to bunched boustrophedon loops.

And to lie beside the summer-tilted blinds in a sun-stripe shift of brown

and gold, with the scent of thyme from the hidden garden’s dog bark,

bee buzz, biplane snore, is to you dream you wake in the aqueous light

of green glass louvres, the sliced ice of your long-ago brother’s room,

a sleep-out with terrazzo floor, Buck Rogers comics under the bed,

night fears in a secret language, and morning’s, the first sun

totting up ingots: yesterday’s best feng shui rationing parallels out.

Mundane things can turn odd, explorable: Venetian blinds are particularly evocative with their hint of intrigue or nostalgia – from their name maybe: degrees of tilt as communication or secrecy. JJO

Jan Owen lives at Aldinga Beach, fifty kilometres south of Adelaide. Her translations from Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal were published in 2015 by Arc Publications. A New and Selected, The Offhand Angel, was published by Eyewear in 2015, and The Wicked Flowers of Charles Baudelaire came out with Shoestring Press in the United Kingdom in 2016. She was awarded the 2016 Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal.

Jan Owen lives at Aldinga Beach, fifty kilometres south of Adelaide. Her translations from Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal were published in 2015 by Arc Publications. A New and Selected, The Offhand Angel, was published by Eyewear in 2015, and The Wicked Flowers of Charles Baudelaire came out with Shoestring Press in the United Kingdom in 2016. She was awarded the 2016 Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal.

Poems

how strange and Viennese you are today Adelaide

like the skating rink in front of the Rathausplatz

here I am finding it hard to stay upright too

every step I take is cautious

ambulant

still moving

I wonder if it’s a frozen river

that I’m skating on the Blue Danube

or a smaller tributary

building to crescendo?

of course

after the rain last week the Torrens

is covered over with a layer of earth

silt

like sheets of brown ice shifting

glacially

patiently

it’s the Black Swans

traversing pontoons of leaf litter with

circumspect

spindly legs

it’s an abandoned bike I see

the same single speed

that I have walked past for weeks now

chained to the thin trunk

of a plane tree by the smokers’ tables

it’s these same barren trees that

deciduous

arthritic

creak and bend in the wind

but won’t uproot

walking between the Exeter and the hospital

past the Elephant and the Palace Nova

it’s the sun

low in the sky that warms my back

and it’s the light

that like a tourist bends down

and tries to pick out one of the dollar coins

embedded in the footpath

that makes me think this is all

positively Hapsburgian

Eating a burrito in the Festival Theatre foyer hair in a half-up half-down

Watching umbrellas & people blow through the door looking for E and her mother

Are they wearing furs? Where are they? E loves the theatre doesn’t come late

Two girls walk past in Year 12 jumpers & I never went to my five-year reunion

Hung up these portraits on the wall have no names on them are we supposed to care?

The play is Things I Know to be True & someone has a ticket for me I assume

To say thank-you I order three glasses of Sauvignon Blanc but forget to get one for myself

From the balcony I oversee a roomful of chairs inflate into a room full of eyes

Gin says that she just finished The Beginning of Spring translated from the Russian

Viv says the stage lighting is supposed to be fantastic & I want to agree but hesitate

Til never had any formal training as an actress but her father is the lighting designer

P points out that her last name is hyphenated in the program nonetheless

I cry in Til’s monologue & E passes me her glasses because she knows

I struggle in low-light looking far away into the distance

I sit with you and watch you smoke cigarettes in front of me

you take photographs but not here not of me

I didn’t ask for sugar in my coffee but I didn’t return it either

when the bus leaves you will be on it when the sky opens you will be beneath it

one day in the future we will agree on something

the first time we met the last time we will kiss

but these are kept safe between us

there is icing on the carrot cake and I let you finish it after you tell me

it is the only thing you have eaten so far today

the five words of overheard French you translate to me make me love you even more

though they are not beautiful words

your sketches remain upside down in my notebook your name

written across every page

after ‘Dug and Digging With’ – AEAF, July/August 2016

Looking forward to seeing you all day

& arriving at the crowded gallery steps

I say ‘this gallery is full of the same people

desperate to see something different’

but I don’t really believe this I mean I am

only here to see you & like this room

is lit just to accentuate your

best features the more I look at you

the more I find myself lost inside a mirrored

box the kind that disappears into itself

it’s called ‘smoke and mirrors’ I’ve played it

before a mis-en-abyme a play

within a play (‘played’

& ‘playing with’) it doesn’t

make any more sense this time around

yet the writing is on the wall

I have to squint to read it but it’s there

the writing is on the ceiling too & it says

‘BLENDED RUBBER TRUMPETS

UNDER A CAR SEAT’

during the performance piece I let you buy

me a beer it goes straight to my head

like black helium balloons I get high

on this darkened ellipsis ...

everyone is being silent/polite there is

a Foley track a throbbing? my own heart?

a pulsation like the pattern of light

from a lighthouse penetrating your porthole

should we run aground

it’s turtles all the way down

turns out it’s only three pedestal fans microphones

we see what we want to see I guess

‘it’s the bubbles’ you whisper & we all clap

very loudly at exactly the right time

for the first time there’s a line for

the bathrooms at the AEAF

the companion text says this is not a ‘problem’

but a ‘secret geometry’ an inside joke

& when I come back out you are talking to

someone you always seem to know

more people than I do regardless of

where we are together you are

looking over some featureless shoulder

kneeling beside a box of books (as art)

I say to whoever is listening ‘if galleries are

the new cathedrals I’m glad we’ve

worked out how to get people

genuflecting’ & upright by the exit sign

I am overcome by the fresh paint on the walls (not

paintings) this is new (nauseating?) over

powering yes the crowd spills out onto the steps

for cigarettes I open my stick of gum

that says: BEWARE THE ARTWORKS. SOME ARE

FRAGILE & you wave to me start walking over

when Aida grabs your arm & says:

‘I’m supposed to stop you running into it

see this sculpture is made

of glass’

Listening to my own listless heart beating & you

beside me I discover we are minor seconds apart

tragic-chromatic but if subtle harmony does exist

it’s a three-year-old playing fists palms & elbows

we manage to stay out of each other’s way mostly

save for collateral clashes/catastrophes: collisions

& rhythms? look at this ventricular wall I put up

meaning: I stay regularly irregular (always on time)

not jazz or syncopation but syncope synecdoche:

tickling the ivories ‘you are the music until the music

stops’ & with the train approaching the boom-gates’

chiasmus suggests crossed purposes my piano

teacher’s arm reaching across me she played the

C# and I the C our fingers almost touching when

she said ‘that’s it there, you’ll never forget it now’

Dominic Symes has had poetry published in Voiceworks, Award Winning Australian Writing (2016), Coldnoon (India), and Broadsheet (New Zealand). His reviews and criticism have appeared in Cordite Poetry Review. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide and curator of ‘NO WAVE’, a reading series commencing in mid-2018.

Dominic Symes has had poetry published in Voiceworks, Award Winning Australian Writing (2016), Coldnoon (India), and Broadsheet (New Zealand). His reviews and criticism have appeared in Cordite Poetry Review. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide and curator of ‘NO WAVE’, a reading series commencing in mid-2018.

Poems

I walk through an industrial landscape

in the painful adolescent hours

before sunrise

above the sky has sobered up

but the high tensions wires

are still dripping

with conversations

long after rain has fallen

traffic lights turn

green

orange

red

city streets are wind blown

with electric light

underfoot

leaves have formed

the first rough draft

of autumn

the early morning sky

has bled out all over

the snug tiled roofs

and tranquillised gardens

of a Buddhist monastery

the air is a medley

with yellow and orange

shavings of sunlight

in the dormitory’s courtyard

well-bred leaves

are falling like penances

stone buildings stand mute

with only a monologue of prayer bells

sounding out each hour

in the commune kitchen

a group of young backpackers

eat their rice and fruit in silence

before their travels will take them

to Thailand Paris Brazil

while outside a monk walks along

the path

chanting a mantra

journeying form one end of his world

to the other

1.

the barbed-wire sounds

of crows

has fetched out the sun

from behind

the ridge

daybreak

has saddles up

the sky

2.

along the river

the mist is chain

smoking

otherwise the only

bright moments

are the small hoof prints

of sunlight

treading

over paddocks

3.

a river

untethered

at one end

its muscular frame

is narrowing out

and browning

as it stretches across

the plain

a rubber band

4.

a herd of caravans

are grazing

waterside

from a camp site

a fishing line

has been cast out

holding the river

in place

like an anchor

Friesian cows are leaning

over the fence

their eyes are an intense study

of nothing

a bus load of Japanese tourists

stop

the cows take black and white

snap shots of them

When a

child

dies

A cross

is made

in woodwork

Angels

are drawn

in the art room

The school flag

is hoisted

to half mast

In the assembly hall

vases of lilies

are placed

At recess

the children sit together

a little tighter

The playground

swing has

a minute’s silence

Jules Leigh Koch was born in Sydney and raised in Adelaide. He is the author of five poetry collections and has been a recipient of two South Australian Literature grants in 2008 and 2011. He has conducted poetry workshops in schools and colleges and at the South Australian Writers Centre. He has also worked as a mentor for emerging poets from Friendly Street Poets and the Richard Llewellyn Arts and Disability Trust. His professional life is spent working with children with special needs in educational settings.

Jules Leigh Koch was born in Sydney and raised in Adelaide. He is the author of five poetry collections and has been a recipient of two South Australian Literature grants in 2008 and 2011. He has conducted poetry workshops in schools and colleges and at the South Australian Writers Centre. He has also worked as a mentor for emerging poets from Friendly Street Poets and the Richard Llewellyn Arts and Disability Trust. His professional life is spent working with children with special needs in educational settings.

Poems

T.S. Eliot's couch

There was once a couch in the Grolier Poetry Bookshop

in Cambridge where T.S. Eliot snoozed.

Send out scouts to track it down and when they do,

stand two strong men, one at each end.

Let them count and on the shout of three

lift it from the place where it has lain

all these years and, with a small boy

to clear its course, carry it to the truck.

Let them secure it with silken cords and waving

like rock stars, escort it down Massachusetts Avenue,

the boy in the cabin come along for the ride.

When they reach the shop where once it nursed

the injured egos and lost lexicons of poets past,

(both the full-of-form and the sadly slight)

let there be a park directly in front, shopkeeper Carol

smiling beside the door flung wide and, behind her,

if you care to climb the stacks, poets A–Z –

among them, propped up by Eberhardt

on one side and Emerson on the other,

Eliot, catching a cat-nap between browsers.

With the reverence due a hallowed relic,

let the two strong men return it to its corner alcove

and with a cold beer apiece, watch

as the small boy, staking first claim on new life,

leaps about on its cushions,

sends dust motes to write on the air like smoke.

One minute the bird is cutting a curve – blue

in two, the swift repair of air – the next,

it’s glottal-stopped in the throat of a dog.

Beyond lies the dog’s muscled tongue-hug

forcing the bird in a slavered-leather

slide past the pharynx, down the gullet

into the gunge and gore of a slaughterhouse floor.

From their front row seats in the corporate box,

the Fates look up from cotton, cloth, and shears,

bite their juridical lips and then decree

that, just this once, one little bird need not

a swallow make. Instantly the dog,

acceding to their thumbs up, sputters a cough,

and from his yawning gawp there flies the bird.

Peter Roget suffered from depression, disconsolation,

gloom, melancholia, pessimism ...

He lived a life of bitterness, desolation, grief, irritation,

lamentation, misery, pain ...

Not that there weren’t periods of bliss, exuberance,

happiness, joy, light-heartedness ...

Not that he wasn’t awake to the wonders of the world,

to its beauty, brilliance, grace, loveliness, magnificence ...

After a visit to the village of Inverkeithing in the Scottish Highlands,

he recorded in his diary that it was beautiful.

When he first set eyes on the meandering water of the Tay,

he wrote that it, too, was beautiful.

And as for the riverbanks near the village of Dunkeld,

his diary asserts that they were remarkably beautiful.

That his thesaurus was still fifty years away

is perhaps worth mentioning.

After Karin Gottshall

Sometimes I say I’m going to meet my mother just because

I like saying it. I like it for its mouth feel and pleasure:

... meet my mother.

It was a phone call at 3 am drove those words away.

Three years later, with no conscious effort on my part,

they followed an overgrown but still navigable path

all the way to my mouth that they might line up

and spill from it just as they used to:

I’m going to meet my mother.

Some days, I go to the Broadway Cafe and sit at a table

for two, one with a view of the sea. She loved the sea.

Mothers come and go, some with daughters, some not.

Each time the door opens, I look up and imagine her

standing there in the Chanel suit she made herself;

a smile crinkling her eyes, her hair blown about a bit.

Then, the sea suitably gazed upon in her stead,

I check my phone and pretend to read a message

that could well be from her in which she says,

‘Sorry, the cake’s taking an age to cook,

can’t think why, what about tomorrow?’

London 2016

At the National Gallery I pay sixteen outraged pounds

to view the Beyond Caravaggio exhibition. No chiaro

to speak of, only scuro, each canvas caked in mud-brown

and bad-blood red on a background of black black black.

I dodge the ladies of the U3A religious art class, decline

the complimentary depressive illness, and in a quick scan,

meet the resentful eyes of a carping King of the Jews.

He parts the flesh around a deep gash in his side. ‘Look!’

he cries. ‘As if crucifying weren't enough!’ I’m defensive

as a guilt-edged politician who can’t say Sorry.

The flight into Egypt fills the opposite wall: Joseph,

the sleep-deprived stepfather, flat-backed, out cold; Mary,

her frock undone, nipple dripping milk, martyring herself

to the earthly demands of a smug and smiling Jesus,

his know-all tell-nothing gaze double-daring disbelief.

I make a dash for chiaro, albeit in the grey day

that leans on the railings overlooking Trafalgar Square.

Its spouting fountains, puffed-up pigeons,

and 23-foot bronze thumbs-up on the rent-a-plinth,

are all I need of heaven and a welcome relief.

Louise Nicholas is a semi-retired teacher and long-term member of the Adelaide poetry community. WomanSpeak, co-written with Jude Aquilina, was published by Wakefield Press in 2009, and a chapbook, Large, by Garron Press in 2013. Her collection, The List of Last Remaining, was shortlisted for the Adelaide Festival Unpublished Manuscript award and was subsequently published by Five Islands Press in 2016. A collection that incorporates her own and her mother’s writing is due for publication in April 2018.

Louise Nicholas is a semi-retired teacher and long-term member of the Adelaide poetry community. WomanSpeak, co-written with Jude Aquilina, was published by Wakefield Press in 2009, and a chapbook, Large, by Garron Press in 2013. Her collection, The List of Last Remaining, was shortlisted for the Adelaide Festival Unpublished Manuscript award and was subsequently published by Five Islands Press in 2016. A collection that incorporates her own and her mother’s writing is due for publication in April 2018.

Poems

standing on the Puente Romano

in Cordoba

watching the rio Guadalquivir

run beneath

like time itself

I do the math

2,000 divided by 44=45

history is nothing more than this

45 times a life of error and uncertainty

the main lesson of monuments in Europe

for which you only queue twice

unless you want the audio guide too

but mostly we take the negative capability option

in the face of poor signage or poor French

and let our consciousness run freely

against the object

sounding it out

although sometimes I feel a need

for an audio-guide to life

an authoritative-sounding voice

with a haughty accent

telling us how magnificent it all is

and not to expect too much

from the vaguely unsatisfactory present

I guess that’s what literature is

one never-ending guidebook

with tips from those

who’ve done it all before

and our own collisions

with objects and texts

which give us something to say uniquely

and one might call poetry

while I won’t be leaving

any monuments

and have conquered little

beyond a 700 square metre block

in an outer suburb

I hope these notes

help the next person.

I wake up

in the middle of the night

in a panic

about my dead-end job

the credit card

the housing market

until poetry appears

like a window

I go through

& compose

a couple of works

of genius

by day light

they won’t be much

of course

but it’s enough

to get me

through the night.

Wednesday 28 November 2016, Adelaide

the day of the storm

I had a poetry reading

with Nathan Curnow

overland from Ballarat

to launch his collection

The Apocalypse Awards

an hour into the unprecedented

statewide blackout

I took his call

you bastard

you brought the apocalypse with you

the reading cancelled

I waited around in the darkness

still in the office

with a swag of poetry books

and no way to get home

on the electric train

the city outside in gridlock

the rain stopped

I ventured into the half light

people wandered the streets

with fear on their faces

and nervous laughter

cars bumper to bumper

I decided I’d walk to my father’s

he lives about an hour’s walk north of the city

I passed a huddle of Ministers

scheming down the steps of Parliament House

toward the intersection

of King William Street and North Terrace

where bystanders stood transfixed

watching a fire truck

stuck in the middle of the intersection

sirens wailing

a man in high viz gear

consulted with the driver

and eventually the truck

negotiated a way through

the politicians stood there

with blank faces

some partially shielded by their advisers’ umbrellas

guys I’d written dozens of speeches for

powerless now

like the rest of us

I walked towards North Adelaide

most of the shops were closed

I realised I had no cash

the Oxford had a hand written sign

on the door of the front bar

in blue pen

open ‘til 6 pm

inside a few punters

nursed beers in candle light

I walked on past the banked up traffic

feeling the weight of poetry books

on my back

their ink would outlast

the electronic readers

though even libraries burn

I felt hungry

and wondered if my father

had food in his house

he’d have long-life milk

tinned food and cash

I was a teenager again

lobbing at his door

broke and hungry

tired from the walk

how much longer

will I have this refuge?

six months ago

I held his hand

while he lay sedated

for four days

following a triple bypass

when they finally roused him

he asked me if he was married

and I had to break the news

not once but twice

and twice divorced

our roles reversed

as he pieced together his life

and I answered the big questions

like how we came to be here

as the days passed the fog cleared

and here I was now at his door

the dog barking

that’ll teach the stupid bastards

to close Port Augusta Power Station

we’d driven by it the year before

observed the stream of smoke

rising from the stack

and he’d posed the question then

how that thin trail of emissions

in so much space

could impact on the atmosphere

and now I see his carbon-based world view

vindicated as the batteries on my phone

run down and before long

the device is useless

while on my wrist

the LED lights of my smart watch

flash wastefully in the candle light

as my father discourses

on candle power

and how they used to have

six candles at each end of the table

he tells me

the smell of burning wax

brings back memories of the block

on Maize Island in the Riverland

while for me the blue kerosene lantern

brings back memories of my own childhood

camping on the block

amidst the ruins

of his ancestral home

and I guess all the old timers

will be thinking of the ‘56 flood

I remember him telling me

as a child

it would happen again

but I couldn’t imagine the Torrens River

ever bursting its banks

and now the dams and reservoirs

are full and the Torrens gushes past the weir

I’m in the right place to survive the apocalypse

my father’s world of hand tools

his brace and bit with assorted augers

rip saws and other tools

he’s never owned a power tool

we haven’t had a blackout this good

in a long time

he exclaims happily

and for once isn’t alone with the TV

we suck on cask wine

I pull out my new chapbook

and finally get to show him the poems

he takes his time reading the book

and I wonder why I haven’t found time

to share some of the poems

over two years old now

we hold our own slow reading

in the candle light

my swag of books not wasted

and after a few hours

I borrow his VS Commodore

to drive home

through the windswept darkness

negotiating intersections

without fear of breathos

when I hit the southern suburbs

order is restored

the lights are back on

as the grid is built up

suburb by suburb

I’m reunited with my family

impressed by their resourcefulness

and by morning

I’m awake to both sides of politics

working the airwaves

renewables vs energy security

Turnbull stoking the coalfires

Weatherill weathering the storm.

a flock of starlings

rises like applause

from the roof

of her Majesty’s Theatre

I met Ted Berrigan

in a dream

wearing a T-shirt

standing in a sparsely

furnished room

the early Berrigan

not yet bed ridden

but distinctly

pot bellied

& the beard

of course

it was a vivid dream

I can’t remember

if he said anything

literary

but he seemed pleased

to be there.

Steve Brock published his first collection of poetry The Night is a Dying Dog (Wakefield Press) in 2007, and received a grant from Arts South Australia for the completion of Double Glaze, published by Five Islands Press in 2013. He is the co-translator with Sergio Holas and Juan Garrido-Salgado of Poetry of the Earth: Mapuche trilingual anthology (Interactive Press, 2014). Steve completed a PhD in Australian literature at Flinders University in 2003. His work has featured in the Best Australian Poems (Black Inc.) and has been published in journals in Australia and overseas. His most recent collection is the chapbook Jardin du Luxembourg (Garron Publishing, 2016).

Steve Brock published his first collection of poetry The Night is a Dying Dog (Wakefield Press) in 2007, and received a grant from Arts South Australia for the completion of Double Glaze, published by Five Islands Press in 2013. He is the co-translator with Sergio Holas and Juan Garrido-Salgado of Poetry of the Earth: Mapuche trilingual anthology (Interactive Press, 2014). Steve completed a PhD in Australian literature at Flinders University in 2003. His work has featured in the Best Australian Poems (Black Inc.) and has been published in journals in Australia and overseas. His most recent collection is the chapbook Jardin du Luxembourg (Garron Publishing, 2016).

Poems

Steve Brock began writing in the shadow of the New York school, but in ‘dreaming with Ted Berrigan’ – ‘I can’t remember if he said anything’ – might be saying goodbye to those earlier cool dudes and already anticipating the more variable temperature of South American poetry. He has spent a lot of time in Chile especially, and has translated extensively from the Spanish. Of course, Latin American models are a pretty broad canvas. Just to take the temperature of Chilean poetry – Nicanor Parra is drop-dead cool, Neruda is hot. What seems to be emerging on Steve’s recent work is a relaxed, often laconic style which is heading back home across the Pacific to be its own influence. It is deceptively unrhetorical, but it contains multitudes.

Coleridge said we are given the Beautiful – but we must ‘seek out, or give, contribute or rather attribute’ the Sublime. Cath Kenneally is a poet of the everyday sublime in her predominantly, but by no means exclusively, small seekings-out, small celebrations, small attributions. Often these take place indoors, as in the word sketch ‘A Rich Full Life’,k which is a still life on a table. Well, a poem is also a kind of drawing or painting: graphite on paper/jet-ink on paper. Kenneally wears her learning lightly, often ironically: she is finally more interested in the infinitely fine texture of the world than generalisations about it. I can see her sitting at that lightly sketched table, drawing – but just as easily I can see her driving a bus through Paterson, New Jersey, jotting her perceptions and ideas in a notebook, the going home to where Ken Bolton has been cooking some zanily decorated cupcakes. If that’s too obscure a reference; check out Jim Jarmusch’s movie (Paterson, 2016).

I don't know if Jules Leigh Koch has read the postwar East European minimalists, and their tight, poetic compressions in which no word is wasted, in which the silences – the whitenesses – between the lines are as important as the words. Is it the metaphors Leigh Koch rejects that makes his poems so fine? Or are the whitenesses the witnesses? Another fine Adelaide poet, Rachel Mead, puts it better than me: ‘Koch makes an art of distilling urban environments down to a series of spare, potent images, reminding us that each day we never walk out into the same world.’

Louise Nicholas has published widely for some years, but I still feel she one of the undiscovered treasures of this poetic town – and this poetic country. She is an alumna to some extent of the Jan Owen’s Aldinga poetry workshops, but brings her own particular brand of often sardonic humour. Sharon Olds is a favourite, and I can see why – less because of influence, perhaps, than because they map similar terrains. ‘I choose laughter,’ Louise writes in the last poem in her latest book, ‘because it joins the dots, / allows us to find the sense in senseless, / connects us all to the last’. Her carefully thought-through, closely focused autobiographical poems do all of that and more, whether they choose laughter, sadness, wonder, love, or joy.

Jan Owen is one of Australia’s most distinguished poets. Her work has been of the highest standard for some decades, but who’s counting? Her recent translations of Baudelaire have received high praise here and overseas.

There is a terrific poem in ABR: ‘String Says’. It is also terrifically strange, belonging to the category that Les Murray like to call Strange poems, in which are different or unusual poems. Jan told me twenty years ago that I should try writing to write some poems with my left non-dominant, hand – to access strange regions of the brain. I don’t know whether Jan wrote that with her left, or right, or both, stereo – but her Muse comes multi-armed, like a Hindu goddess.

Dominic Symes is an emerging voice on the Adelaide Poetry scene. I first heard him in Ken Bolton’s legendary in their-own-lifetime Lee Marvin readings (now legendary beyond their lifetime, sadly) and to some extent he is another alumnus of the New York school through Ken’s tutelage – but there is a personal, particularly subjective strain emerging. And maybe my ear is pre-programmed by my own predilections, and maybe I’m straining to hear it, but more recently there is also East European strain which may be genetic – he has a Slovakian grandfather.