- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Israel

- Custom Article Title: Danielle Celermajer reviews 'Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, leader, statesman' by Itamar Rabinovich

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, leader, statesman

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $37.99 hb, 272 pp, 9780300212297

There are intimations of a humanist universalism from the outset. When Rabin wrote in his autobiography about the psychological difficulties that his soldiers experienced expelling Palestinian civilians from Lod and Ramla during the 1948 War, he explains their suffering as the moral conflict such actions provoked for young Jewish men ‘inculcated with values such as international fraternity and humaneness’. Interestingly, like the censors who edited Rabin’s autobiography, when Rabinovich recounts the reflection, he omits these last words. And then there was Rabin’s radical mother – ‘red’ Rosa Cohen – who broke with both her wealthy orthodox Jewish family and the Communist Party in Russia, and moved to Jerusalem, not because she was a Zionist (on the contrary), but because she thought it might offer her the space to create a life. Amidst a story dominated by forceful and frequently egoistic men, one senses the imprint of Rosa’s independence of mind on her son’s, especially when he reached an age beyond her forty-seven years.

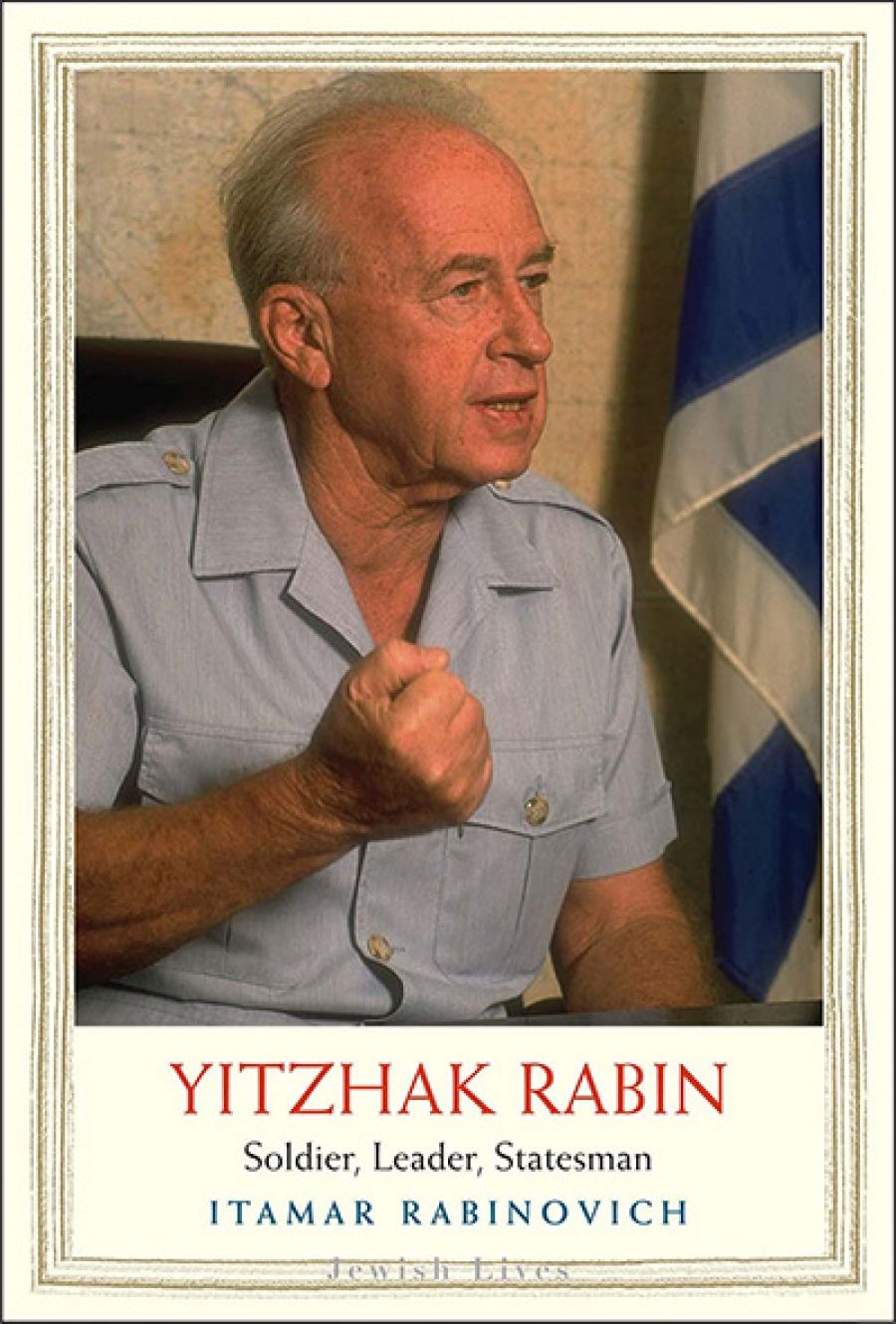

Yitzhak Rabin in 1957 (IDF Archives, Wikimedia Commons)Unlike the other ‘great men’ in the history of Israel alongside whom Rabin migrated from military to political leadership, Rabin did not lead his life teleologically, set from the outset on the march towards a pinnacle. Each identity – commander, general, chief of staff, ambassador to the United States, member of parliament, prime minister (1974–77, 1992–95) – grew incrementally from the one preceeding it, and he occupied each in a similarly organic (and thus often imperfect) way. Perhaps it was this quality of presentism that allowed him to act responsively in each role; to understand that principled action is not action obedient to a set of transcendent laws or metaphysical forms, but responsiveness to context, informed by a well set moral compass. This would certainly make sense of the answer that Bill Clinton recalls Rabin gave when he asked him, privately, after the signing of Oslo II, why he had done it. First, he said, his country was his life, and unless the State of Israel found a way of sharing the future – including the land – with the Palestinians, very soon Israel would either cease to be a democracy, or cease to be a Jewish State. Either, he said, would violate their solemn obligations. Second, he said, Palestinian children are also humans and they too deserve to grow up with a sense of home.

Yitzhak Rabin in 1957 (IDF Archives, Wikimedia Commons)Unlike the other ‘great men’ in the history of Israel alongside whom Rabin migrated from military to political leadership, Rabin did not lead his life teleologically, set from the outset on the march towards a pinnacle. Each identity – commander, general, chief of staff, ambassador to the United States, member of parliament, prime minister (1974–77, 1992–95) – grew incrementally from the one preceeding it, and he occupied each in a similarly organic (and thus often imperfect) way. Perhaps it was this quality of presentism that allowed him to act responsively in each role; to understand that principled action is not action obedient to a set of transcendent laws or metaphysical forms, but responsiveness to context, informed by a well set moral compass. This would certainly make sense of the answer that Bill Clinton recalls Rabin gave when he asked him, privately, after the signing of Oslo II, why he had done it. First, he said, his country was his life, and unless the State of Israel found a way of sharing the future – including the land – with the Palestinians, very soon Israel would either cease to be a democracy, or cease to be a Jewish State. Either, he said, would violate their solemn obligations. Second, he said, Palestinian children are also humans and they too deserve to grow up with a sense of home.

What I am calling responsive principle though, others deemed treachery deserving death. The circumstances of Rabin’s assassination are etched in history, but many may not know about the rabbis who lent religious sanction to the murder, the extreme right-wing political groups who incited it, and the Likud members who created a permissive environment for hatred to flourish. In 1994, as the incitement campaign was gaining strength, Benjamin Netanyahu, then the new leader of the Likud party, attended an anti-government march in a town north of Tel Aviv, organised by the ultra-nationalist Kahane Hai. He was seen marching between a coffin inscribed ‘Zionism’s murder’ and a person carrying a gallows.

Yitzhak Rabin, Bill Clinton, Yasser Arafat, 13 September 1993

Yitzhak Rabin, Bill Clinton, Yasser Arafat, 13 September 1993

(photograph by Vince Musi, The White House)

As history alone, this makes for a deeply sobering image. In a contemporary political scene where democracy is increasingly giving way to incitement against those whose vision departs from one’s own, it ought to call each of us to be more than an image of our native landscape; or to imagine that landscape more capaciously.

Comments powered by CComment