Politics

Into the Woods: The Battle for Tasmania’s Forests by Anna Krien

On the day that I finished reading Into the Woods, I opened the newspaper to a report that Gunns was withdrawing from native forest logging to base its future business entirely on plantation-grown timber. Given that Gunns controls almost eighty-five per cent of the wood products traded in Tasmania, this has raised hopes of an end to the decades-old forest w ...

The Politics of Prisoner Abuse: The United States and Enemy Prisoners after 9/11 by David P. Forsythe

Many of us would find it as hard as Shaw’s Ladvenu does to think of any good reason for torture. It seems medieval, it is abhorrent, it is internationally illegal, and it doesn’t work. Statements made under torture are legally useless, and their value as intelligence is not much better ...

... (read more)A Different Inequality: The politics of debate about remote Aboriginal Australia by Diane Austin-Broos

Many Australians are hungry for answers to Indigenous disadvantage. In recent years, anthropologists have been among those who have proposed solutions. This latest offering is from Diane Austin-Broos, professor emerita at the University of Sydney and long-time ethnographer of the ...

... (read more)David Karoly reviews 'The Garnaut Review 2011: Australia in the Global Response to Climate Change' by Ross Garnaut

Climate change is often framed as a number of battles: between science and opinion, sustainable development and economic growth, government control and individual freedom, or environmentalists and business leaders. All of these are simplifications of the complexity involved in our modern world’s developing adequate responses to human-caused climate change.

... (read more)Liberty: A History of Civil Liberties in Australia by James Waghorne and Stuart Macintyre

In 1988 the Hawke government put a constitutional amendment to a referendum. On the recommendation of the government’s Constitution Commission, we were invited to vote to enshrine guarantees of trial by jury, property rights, and freedom of religion. The proposition was rejected by all states. There is nothing surprising in that. We almost always do vote against constitutional amendment because the politicians of the right have always succeeded in persuading us that the original document (a free trade agreement between the federating colonies) is perfect and, in any case, any proposal for change is a left-wing plot to deprive her majesty’s loyal subjects of their common law freedoms.

... (read more)Labour and the Politics of Empire: Britain and Australia 1900 to the Present by Neville Kirk

In 1902 the New Zealander William Pember Reeves published a pioneering study of social innovations in Australia and New Zealand. He wrote it, he said, for the ‘increasing number of students in England, on the Continent, and in America who are sincerely interested in them’ ...

... (read more)In 1963, ASIO opened a file on a disreputable fellow named Laurie Oakes, who was then living with Alex Mitchell, another Daily Mirror reporter. The two men came to the spooks’ attention when Mitchell suggested hiding unionist Pat Mackie from the police ...

... (read more)The Obama Syndrome: Surrender at Home, War Abroad by Tariq Ali

Tariq Ali, proclaims the Guardian, ‘has been a leading figure of the international left since the 60s’. If his latest book is the best the left can muster, I fear that its chances of influencing political debate are minimal – and, even worse, undesirable.

... (read more)Henry Kissinger has never seemed at home in the United States, although he has served in its highest councils and received its richest rewards. When I was one of his students at Harvard, we called him Henry, to distinguish him from professorial luminaries such as Galbraith, Riesman, and Schlesinger. He did not fit the insistent reasonableness of the Harvard faculty. His guttural voice, anxiety to please, mischievous, self-deprecating humour, and fearsome views on nuclear warfare made him an almost unbelievable figure of playful profundity.

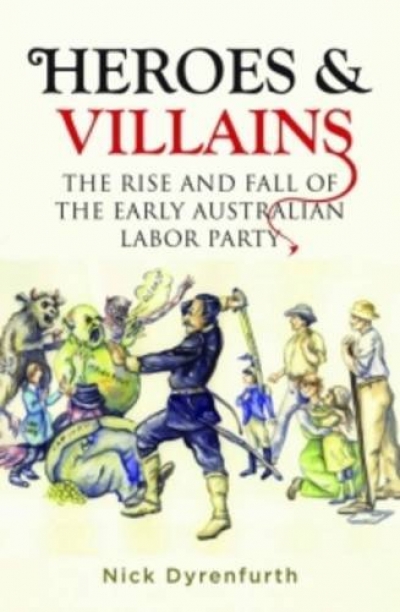

... (read more)Heroes & Villains by Nick Dyrenfurth & A Little History of the Australian Labor Party by Nick Dyrenfurth and Frank Bongiorno

The heroes and villains in Nick Dyrenfurth’s account of the early Labor Party are the cartoon figures in the labour press that he uses to explore its political rhetoric. The heroes are sturdy working men, sometimes in bush garb, sometimes industrial labourers. The villains take various forms: serpents, harpies, bloodsucking insects, menacing aliens, but above all the Fat Man, the swollen, grotesque embodiment of capitalist greed. Dyrenfurth observes that Mr Fat is a far more ubiquitous device in Australian radical iconography than its counterparts elsewhere. British cartoons used a variety of villains: aristocratic loafers, rapacious landlords, ruthless sweaters, mendacious press barons. Those in the United States were less likely to personify capitalism with a generic capitalist villain than to depict combines and trusts.

... (read more)