Australian History

I Am What I Am: My life and curious times by John Marsden

If the world is divided between those who celebrate their birthday in a flamboyant manner and those who don’t, then John Marsden unquestionably belongs in the first camp. At least, he did before his much-publicised fall from public grace. Marsden begins his autobiography with a detailed account of his fiftieth birthday. A full year earlier, he began mailing monthly teaser invitations to his guests. The first read, in capitals: ‘An important invitation. You have been invited to one of the most important events of 1992.’ Each month, more information dribbled out, until the day itself, when a ‘rich smattering of state cabinet ministers; Liberal, Labor and Democrat politicians; lawyers, judges, civic leaders and business heavyweights all made the sunset pilgrimage to a hillside on the edge of town along a darkened stretch of the road.’ The reader gets the message: this birthday boy was one hell of a mover and shaker, a player, a friend of the rich and powerful, and, as the Grange Hermitage flowed freely, one damn fine host; a man at the height of his powers.

... (read more)Kisch in Australia: The untold story by Heidi Zogbaum

An unfamiliar character from a strange land is barred from setting foot on mainland Australia. Desperate to land, he leaps from ship to shore, breaking his right leg in the process. A conservative attorney-general desperate to protect our borders, pursues this man, now on crutches, through the courts. The charismatic stranger wins his court case and holds the government up to ridicule. Shadowed unrelentingly by Canberra’s spooks, he urges Australians to look past their government’s pronouncements and discover for themselves the real dangers to world peace. Whilst history, even in Marx’s cycles of tragedy and farce, never neatly repeats itself, these duels between Egon Kisch, Czech communist, and Robert Menzies, Anglophile attorney-general, do have contemporary import. No doubt this explains why Kisch’s adventures in 1930s Australia have been told several times through film, theatre and books. In this new and enjoyable recasting of the drama, Heidi Zogbaum reminds us of the bare bones of Kisch’s Australian sojourn, focusing for the most part on his successful courtroom battles and European background. These are interspersed with detailed summaries from spies such as ‘Snuffbox’, charged with dredging up the evidence on Kisch’s European activities that led to his eventual deportation.

... (read more)Painting Ghosts: Australian Women Artists in Wartime by Catherine Speck

Those attending art history conferences over the last few years have been beguiled by the papers given to Catherin Speck, based on her research into aspects of Australian women artists and war. Each paper has detailed newly uncovered artists, works and information, and whetted the appetite for Painting Ghosts: Australian Women Artists in Wartime: not a reproduction of Speck’s previous work but fresh information, artists and images (such as Adelaide painter Marjorie Gwynne) placed into better-known depictions of war by artists such as Hilda Rix Nicholas and Nora Heysen.

... (read more)Liz Conor’s accomplished history of the ‘modern appearing woman’ in 1920s Australia has much to recommend it. The archival work that it represents is fascinating and suggestive of a trove of female energy, sadness and invention. Hilarious and ambivalent stories emerge of Sydney ‘gals’ and Business Girls, of a New York flapper with traffic lights painted on her silk stockings, and of Amelia, an indigenous maidservant, who invented grunge without her mistress recognising style when it stepped up to her table in a red skirt, man’s striped shirt and big boots. These and other stories trace the vigour of young women’s determination to respond to the consumer possibilities of a spectacular new world of media images, electric light and postwar male uncertainties.

... (read more)Times & Tides: A Middle Harbour memoir by Gavin Souter

Near a little beach at Northbridge, in the heart of Sydney’s northern suburbs, the vertical rock face carries the image of a whale, about life-size, created by the original inhabitants at some indeterminate date. ‘[B]ecause of its precipitous location,’ says Gavin Souter, ‘one cannot stand far enough away to take it in all at once. Head, fins, flukes and flippers have to be viewed separately, then put together.’

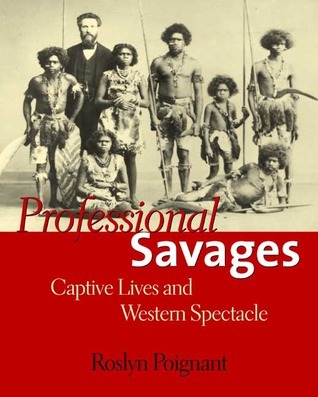

... (read more)Professional Savages: Captive lives and Western spectacle by Roslyn Poignant

One photograph in this beautifully produced book is indelible. It is Paris, 1885, and against a painted show backdrop, Billy, young Toby and his mother pose with their boomerangs and a miniature dog. The disoriented, troubled eyes of these north Queenslanders look you right in the face. The sharp-focus dog, a taxidermist’s creation, paradoxically strikes a more animated stance than the living humans. This macabre depiction of people as ‘types’ led Roslyn Poignant to investigate an historical epic of dynamic performers.

... (read more)Childhood is a fertile territory for writers. Almost all first-time authors hoe it, and some continue to do so for the rest of their careers. Given the chance, most people cannot resist the impulse to reminisce about the horrors and delights of being a child.

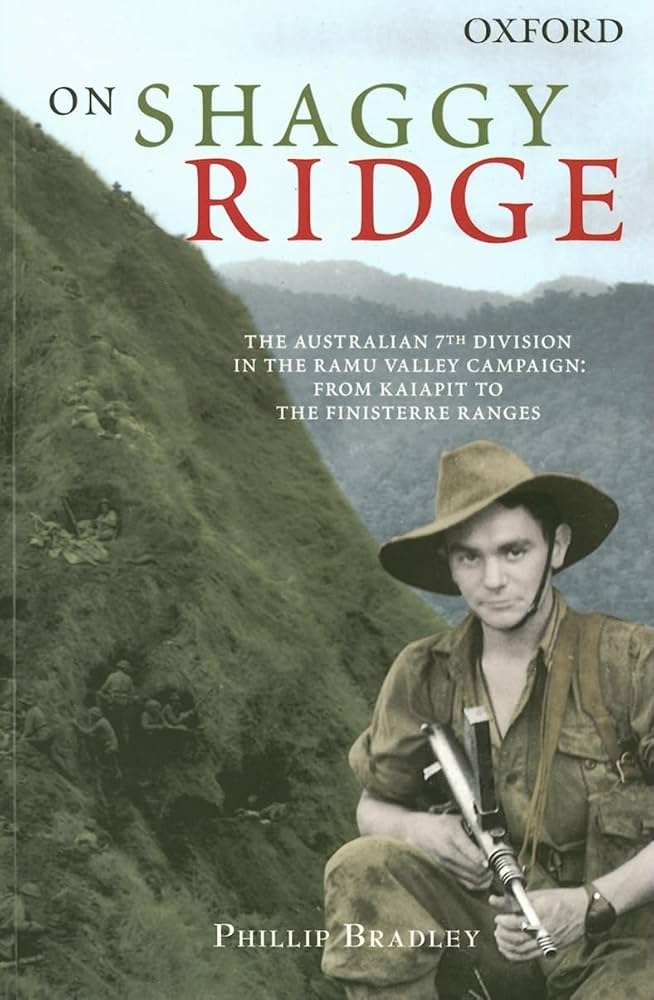

... (read more)On Shaggy Ridge by Phillip Bradley & Kokoda by Peter FitzSimons

Of all the campaigns that took place in the western half of Australian New Guinea during World War II, Shaggy Ridge is among the most neglected. It does not deserve this status. There used to be a graphic, brooding diorama depicting the massiveness of the ridge in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra; unfortunately, it has been removed and replaced by other exhibits.

... (read more)What the hell is Bob Ellis? Discuss. Ellis might put it like this himself. Chances are he’s asked the question of a street window once or twice in wonderment and mock self-mockery. He’s earned it. From the back-cover blurbs down the years, one has got, by way of label, ‘l’enfant terrible of Australian culture’ (The Inessential Ellis, 1992), ‘a kind of dusty national icon’ (Goodbye Babylon, 2002) and now, in a disappointing regression to understatement, ‘a political backroomer’. We can assume, I think, that these are self-descriptions. Another, from the text of Goodbye Babylon, puts it this way:

... (read more)More Than a Game: The real story of the Australian Rules Football edited by Rob Hess and Bob Stewart

In his spirited foreword, well-known football writer Martin Flanagan notes that ‘More Than a Game is in the best traditions of Australian football writing. It is unauthorised, a necessary virtue given the blurring of the Australian media with the corporate interests behind football.’ Flanagan also knows that writing about football in Australia has become a dignified and scholarly pursuit. Still, football as representing the verities of life is a powerful and relatively new symbol. As the editors and contributors amply demonstrate, Australian Rules history has been measured out in tribal rivalries and violence. These two themes, along with many contemporary evaluations, are explored in detail.

... (read more)