Art

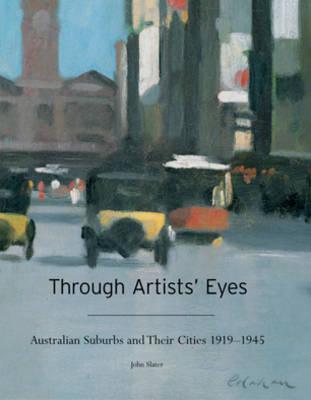

Through Artists’ Eyes: Australian Suburbs and their Cities, 1919-1945 by John Slater

The tempting cover leads to a feast of 164 colour pictures, which you will fall upon with delight. Despite the title, almost all are of Melbourne and Sydney, places most Australians know well enough to enjoy pleased shocks of recognition. There are two highly specific Perth roofscapes, but a futurist speeding tram in Adelaide could be anywhere, and so could the industry at Yallourn, or sexual and racial tension at Townsville in 1942. Even if you come from the bush, you will know the city markets, cathedrals, law courts, showgrounds, Circular Quay and Harbour Bridge, Flinders Street Station and Collins Street trams, Town Hall concerts, Tivoli showgirls, Manly, St Kilda, racy Kings Cross lats, a frisson of ‘slums’. The author says he chose the works of art solely for their subject matter, yet he certainly appreciates aesthetic force. It’s a lively anthology of transport and other social nodes, parklands, beaches, building construction, shopping, entertainment. It makes the familiar look unexpectedly interesting.

... (read more)Peter Timms is ‘dismayed’ by the state of contemporary art and by the hype that surrounds it and the reality of the experience. He has written a book mired in exasperation and frustration. It is not hard to share Timms’s sentiments. Visit any sizeable biennale-type exhibition and you are engulfed in flickering videos in shrouded rooms, installations of more or less hermetic appeal, large-scale photographs – these often prove to be the most interesting – scratchy ‘anti-drawings’ and a handful of desultory paintings. Noise is ‘in’, too. ‘Biennale art’ is the term frequently used to describe the phenomenon.

Quite who is to blame for this occupies much of the first half of Timms’s book. Artists hell-bent on having careers rather than seeking vocations are part of the problem, and so are curators of contemporary art who nourish the artist’s every need. Art schools are next, where cultural theory has replaced the teaching of art history. The superficialities and the susceptibility to trendiness in the Australia Council are further contributors.

... (read more)The exhibition murmured, with Baudelaire, of Correspondences. Wesfarmers’ collection has a high proportion of major paintings, each warranting close attention. What elated me, however, was the unusual rightness of the play between works of art. It was years since I had seen a non-thematic display (the Sublime is limitless, so hardly a theme) that reached into works of art obliquely and exercised the art of comparison with true inspiration.

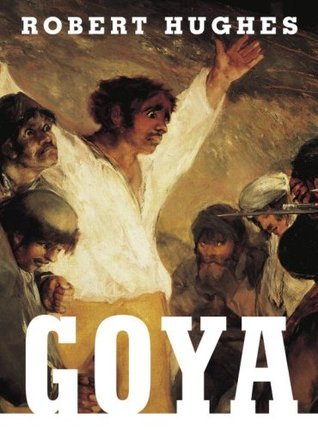

... (read more)An appreciation of Goya, contends Robert Hughes, has become essential for Europeans wishing to make themselves literate in their own culture. Goya’s significance is heightened because his works are arguments for humanity, to be balanced against the horrors he depicted. Goya (1746–1828) indeed remains our contemporary. His life, his imagery and his dilemmas resonate at a time when countries are being invaded for their own good, as Europe was by Napoleon, provoking the first guerillas.

... (read more)Robert Hughes, bemoaning the contents of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1959, cast an eye over its sandstone façade decorated in bronze letters with such august names as Rubens, Titian and Raphael, and quipped: ‘Never has so large a nut housed so inadequate a kernel.’ The National Gallery of Australia was in every respect the opposite story: its collection was a fat kernel in search of a shell. Until 1968 this collection, thought to comprise some 3000 works, was strung around Canberra offices and Australian embassies like so much washing on a line. The Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, which would soon be dismantled, had been buying energetically, if conservatively, for years. However, there was no catalogue, no conservator to care for them and no established policy for the collection.

... (read more)Art and Australia by Margaret Preston: Selected writings 1920–1950 edited by Elizabeth Butel

One of Australia’s most significant Modernist artists, Margaret Preston (1875–1963) is often remembered for her relentless self-promotion and her forthright opinions: in particular, for her call to develop an art for Australia, untainted by past and irrelevant foreign art. Although frequently quoted (the wonderfully titled autobiographical article ‘From Eggs to Electrolux’ being one of her best-known pieces), her writings have not previously been gathered together. Selected and introduced by Elizabeth Butel, who has written before on Preston, this book presents twenty-nine articles and one extract. These appeared in a number of publications – art journals, women’s magazines, exhibition catalogues and the like – between 1923 and 1949.

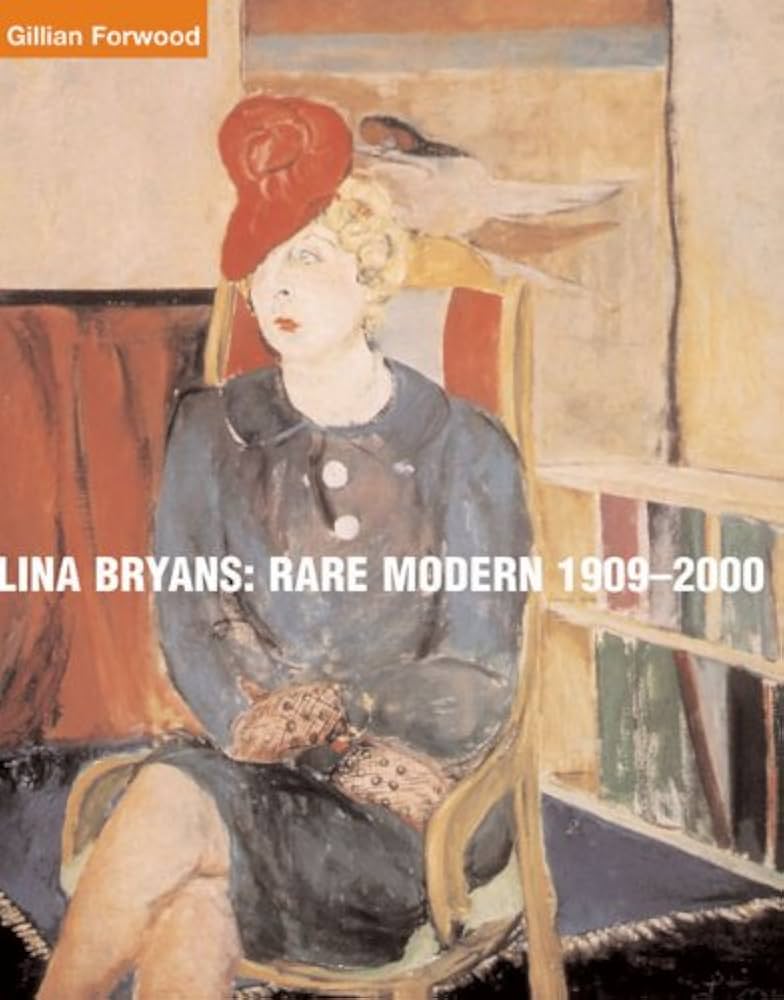

... (read more)Lina Bryans’s painting The Babe is Wise captures the ‘insouciant chic’ of the New Woman in 1940: independent and self-assured, the subject stares at the viewer from beneath a sharply angled hat. A portrait of the artist’s close friend, author Jean Campbell (whose novel inspired the painting’s title), The Babe is Wise became Bryans’s most famous painting, and its subject captures the artist’s own attitude to life.

Gillian Forwood’s handsome new book, Lina Bryans: Rare Modern 1909–2000, recalls the life and work of a brave, unconventional and generous woman who single-mindedly pursued a career as an artist from the late 1930s until her death three years ago. This lavish Miegunyah Press publication serves both author and artist well, reproducing numerous images in colour, many for the first time.

... (read more)Art Deco: 1910-1939 edited by Charlotte Benton, Tim Benton and Ghislaine Wood

A thirty-ish Peter O’Toole becoming an aged schoolmaster with powdered apple cheeks. I was a child when I saw the remake of Goodbye Mr Chips in 1970, but even then I could see that wrinkly make-up will never wash. More fascinating than the film was watching it in Walter Burley Griffin’s Capitol Theatre in Melbourne. The ceiling’s cunningly layered pleats of multi-faceted fittings were a million triangles softened in an illuminated cloud of pink and rose and yellow hues. It was my first knockout encounter with the style known as Art Deco.

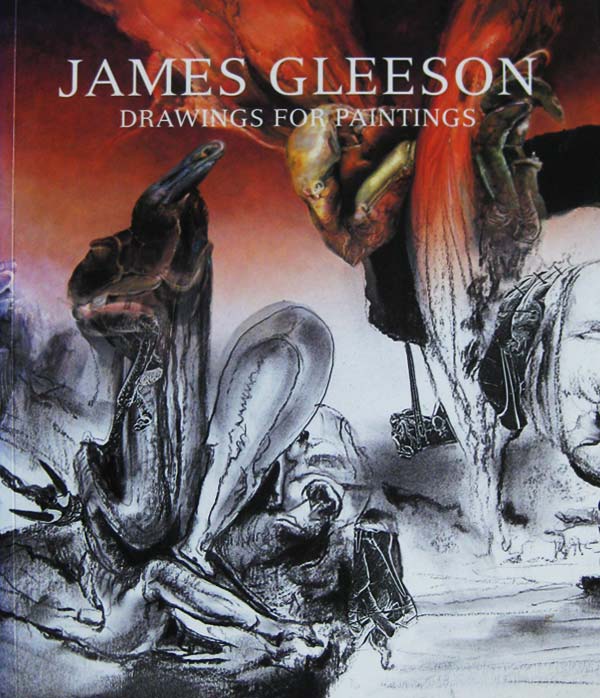

... (read more)James Gleeson: Drawings for paintings by Hendrik Kolenberg and Anne Ryan

Art is divided into three parts – at least for amateur painters who ask, when they begin acquaintance, ‘Do you do abstract, impressionist or surrealist art?’ Of these, surrealism has the strongest interest for a mass audience, and the deepest penetration into popular culture. When it was new, surrealism was quickly appropriated into commercial and advertising art. Today, commercial cinema is awash with some of surrealism’s youthful political idealism, but more with its fantasies of shock-horror and sex.

Surrealist literature never came to much. The artists took over. If Picasso was the greatest twentieth-century artist, his surrealist paintings from the 1920s onwards might be his own best work. Remember how the best exhibition ever produced in Australia, Surrealism: Revolution by Night (National Gallery of Australia 1993, by Michael Lloyd, Ted Gott and Christopher Chapman), showcased Picasso ahead of Miró, Dalí, Magritte and Ernst. And the star of the Australian component of the exhibition was James Gleeson.

... (read more)Occasionally, we bring you thematic issues. The April issue is a good example, the first half being devoted to art and art history. This seemed timely, because of the abundance of major publishing in this area and the energy and controversy generated by current debates about the genre.

... (read more)