Fiction

If you are regretting the passage of another summer and feeling nostalgic about the lost freedoms of youth, Sonya Hartnett’s latest novel, Surrender, may serve as a useful tonic. In Hartnett’s world, children possess little and control less, dependent as they are on adults and on their own capacity to manipulate, or charm ...

... (read more)From the first paragraph, Terri Janke’s Butterfly Song makes its intentions clear: this is a novel about the love of the land and the palpable connection to the ancestral home. ‘They say if you live on an island for too long, you merge with it. Your bones become the sands, your blood the ocean. Your flesh is the fertile ground. Your heart becomes the stories, dances, songs. The island is part of your makeup …’ This is why Tarena Shaw feels an odd sense of belonging when she first steps foot on Thursday Island, her grandparents’ birthplace. Though she has never been there before, the memories and myths that have been passed down the family tree have guaranteed a spiritual bond between the black-suited city slicker and the tropical island with water like a ‘living gemstone’.

... (read more)These first novels by Joel Deane, the Victorian premier’s speechwriter, and Merle Thornton, a former academic who famously chained herself to a male-only bar in Brisbane, focus on radically different social groups. Deane’s Another is about two unemployed adolescents living in an outer Melbourne suburb bypassed by a freeway where the local McDonalds is the town’s nucleus. In After Moonlight, Thornton presents a bookstore-browsing, duck-eating, macchiato-sipping, Carltonish academic. (The novel is replete with such portmanteaux.) That both novels are set in the same city is a shock. Another commonality, more poignant, is a concern with the personal and the enduring effects of tragic pasts.

... (read more)Diane Armstrong should have stuck to the facts. The many surprising particulars that illuminated her two fine histories of the Jewish refugee experience (Mosaic: A Chronicle of Five Generations, 1998, and The Voyage of Their Life, 1999) have been replaced, in her first novel, by clichés and banalities that turn to soap opera her account of an Australian forensic scientist unearthing the secrets of her own past.

... (read more)In a recent feature article in the Guardian Review, William Boyd proposed a new system for the classification of short stories. He constructed seven stringently categorical descriptions and ended his article with a somewhat predictable – that is to say, canonical – list of ‘ten truly great stories’, among which were James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Spring at Fialta’ and Jorge Luis Borges’s ‘Funes the Memorious’. Most of the writers cited were male, and the classifications were confident demarcations in terms of genre and mode (‘modernist’, ‘biographical’). It is difficult to know, and no doubt presumptuous to speculate, what Boyd would make of Frank Moorhouse’s edited collection The Best Australian Stories 2004. Garnering them ‘at large’ by advertisement and word of mouth, Moorhouse received one thousand stories, from which he selected ‘intriguing and venturesome’ texts, many of which display ‘innovations’ of form. Of the twenty-seven included, six are by first-time published writers and twenty are by women. This is thus an open, heterodox and explorative volume, unlike its four predecessors in this series in reach and inclusiveness. It is also, perhaps, more uneven in quality: a few stories in this selection are rather slight; and the decision to include two stories by two of the writers may seem problematic, given the large number of submissions and the fact that the editor claims there were fifty works fine enough to warrant publication. A character in one of the stories favourably esteems the fiction of Frank Moorhouse over that of David Malouf: this too may be regarded as a partisan inclusion.

... (read more)Ugh: today I realised Colleen McCullough’s latest book (her fifteenth), Angel Puss, which ABR sent to me several weeks ago, needs to be read, reviewed and dispatched by January 3. The dust jacket précis reveals that this novel is ‘exhilarating’ and ‘takes us back to 1960 and Sydney’s Kings Cross – and the story of a young woman determined to defy convention’ ...

... (read more)What a phenomenon Bryce Courtenay is. In a world where we are constantly being told that books are on the way out, he sells them by the barrow-load. They’re big books, too. This one weighs 1.2 kilograms and is seven centimetres thick. It’s the kind of book that makes a reviewer wish she was paid ...

... (read more)‘It is in love that violent desires find the greatest satisfaction,’ wrote Stendhal in On Love (1842). Though distanced by land, sea and centuries, Sophie Cunningham’s début novel, Geography, gives contemporary testimony to the same enduring claim. Set for the most part among the suburbs and landmarks of Melbourne and Sydney during the 1990s, Geography travels back and forth in time and place between Los Angeles and Sri Lanka, establishing an expansive mise en scène for this explosive meditation on the complexities of love, sex and self-destruction.

... (read more)Day I – new suitors

The mountain thinks: Wilson, eh? Finally he comes. About time. The trucks stop on the north side where the Rongai route begins and Kilimanjaro’s powdered skirt tumbles out of Tanzania into Kenya. Her lower folds are less sensitive, but she still feels us among the thousands. In her stones she weighs our upward love and thinks: How much do you really want me? We start late and pad steadily from 1900 metres on the trail’s seamy musk with no perspective on the summit. Above us, only a shrug of fat hills and cloud. Kilimanjaro’s broad, high face (all ice-lashes and airless hauteur) is a vast four kilometres further up. Emmanuel tells us to walk polepole (slowly, gently). ‘Like walking your girlfriend home,’ he says.

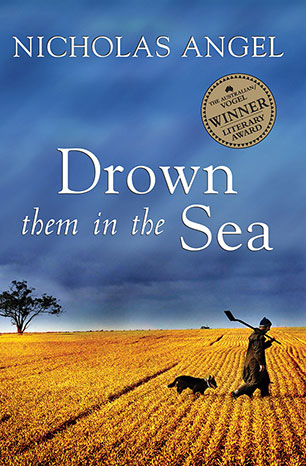

... (read more)Drown Them in the Sea by Nicholas Angel & The Hanging Tree by Jillian Watkinson

Aspiring Australian writers lament the fact that few publishers are accepting unsolicited fiction manuscripts. Those that do accept them lament the fact that they are inundated by around a thousand submissions each year. What’s the solution? Increasingly, it seems, awards for unpublished work with publication as the prize. Writers know their work will at least be looked at; publishers can outsource to judges the culling of what would otherwise be their slush pile. It is no longer just the 24-year-old Vogel Award, with its promise of publication by Allen & Unwin. State-based awards now guarantee publication by UQP, FACP and Wakefield Press.

... (read more)