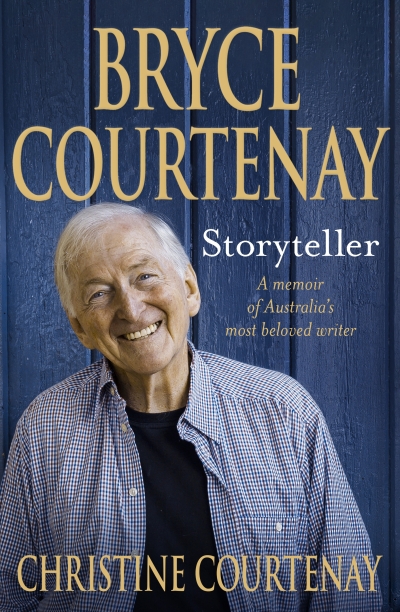

Jacqueline Kent

Yarn Spinners: A story in letters edited by Marilla North

by Jacqueline Kent •

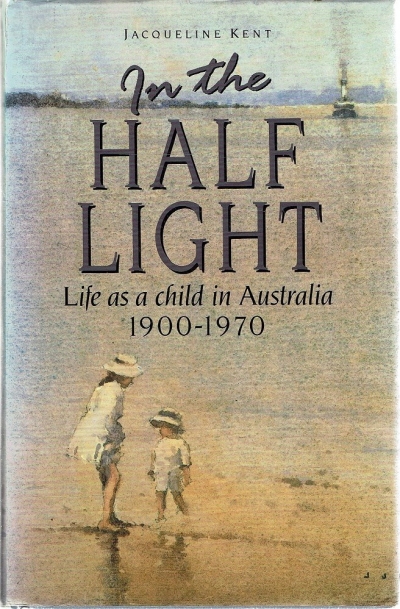

In the Half-Light: Life as a child in Australia 1900-1970 edited by Jacqueline Kent

by Brenda Niall •

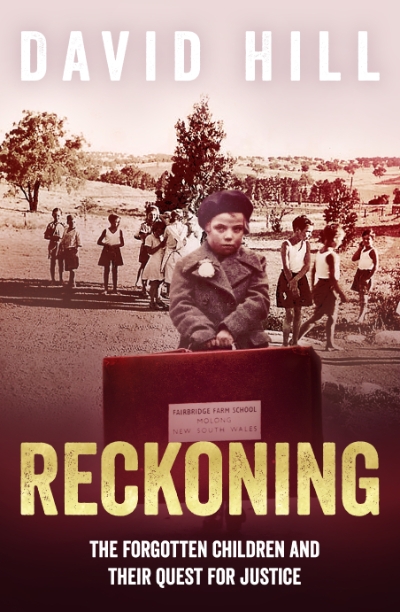

Reckoning: The forgotten children and their quest for justice by David Hill

by Jacqueline Kent •

Killing Sydney by Elizabeth Farrelly & Sydney (Second Edition) by Delia Falconer

by Jacqueline Kent •

It would be good if editors and publishers took smarty-socks reviewers to task occasionally – probably not in public – if said reviewers go on about falling standards in proofreading or editing. Reviewers should, I think, be aware that the course of publishing never did run smooth – maybe with a difficult author, editing disasters, or horrible scheduling problems – and cut a bit of slack accordingly. I’d also like to see readers engage with reviewers, especially if they have read the book and feel the critic’s comments have been unfair.

... (read more)Mary’s Last Dance: The untold story of the wife of Mao’s Last Dancer by Mary Li

by Jacqueline Kent •