Michael Halliwell

Understandably, the focal point of musical interest in Sydney in recent months has been Bennelong Point, more specifically the newly revamped Concert Hall at the Opera House. Central here has been the Sydney Symphony Orchestra under the new leadership of Simone Young, offering a series of wide-ranging and exhilarating concerts. But there has been other music making. Sydney’s indefatigable Sydney Chamber Opera has not been idle, and Friday saw the première of Awakening Shadow, an intriguing new/old work by Australian expatriate composer, Luke Styles, It comprises a melding of original music by Styles that enfolds the five Canticles of Benjamin Britten (1913–76).

... (read more)Over the years, the demise of the solo art song recital has often been predicted, yet the format lives on, sometimes reflecting new approaches and variations on tried and tested practices, but generally remaining within the parameters of a singer and pianist in evening wear on an empty stage. It evolved from informal house concerts in Europe in the late eighteenth century, probably reaching its ‘standard’ setting in the mid to late nineteenth century in the German-speaking lands in a form known as the Liederabend (song evening) ...

... (read more)In the program for the première of Voss in Adelaide in 1986, David Malouf observed:

... (read more)No libretto can reproduce the novel from which it is drawn. A novel, especially a great one, is itself: unique, irreplaceable. The best a libretto can do is reproduce the experience of the book in a new and radically different form, allowing the form itself to determine what the experience will be.

To say that Fromental Halévy’s opera La Juive (The Jewess) is a problematic work is a gross understatement. From the time of its successful première at the Paris Opéra in 1835 – it is one of the finest examples of French Grand Opera – it has been surrounded by controversy, periods of neglect, particularly during the 1930s, and even outright banning; its subject matter has been found confronting and frequently highly polarising. Although considered blatantly anti-Semitic by some, it was the finest opera of a successful Jewish composer.

... (read more)Devotees of Giuseppe Verdi often suggest that the composer’s version of Shakespeare’s Othello is ‘greater’ than the original; a fruitless assertion, but indicative of the esteem in which Verdi’s penultimate opera is held. After Aida (1871), Verdi was enjoying the life of a gentleman farmer. Italian opera of the 1870s and 1880s, however, was facing something of a crisis, threatened by the relentless tide of ‘Wagnerism’, whose theories on opera were embraced by many Italians. Verdi, when asked about his own theory of theatre, drily replied: ‘My theory is that the theatre should be full’.

... (read more)George Bernard Shaw tartly suggested that ‘the chief glory of Victor Hugo as a stage poet was to have provided libretti for Verdi’. Hugo’s fifteen dramas are not well known in the English-speaking world and live on mainly through the many operatic reincarnations of the plays. Most prominent in popular culture, though, is the adaptation of Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, the blockbuster musical. The first successful operatic adaptation of a play was Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia of 1833, which introduced a strong strain of realism into Italian opera. Undoubtedly the most successful of all the Hugo operas is Rigoletto (1851), Verdi’s version of Le roi s’amuse, still one of the most performed operas in the repertoire. Hugo later admitted that the opera was ‘better’ than the play.

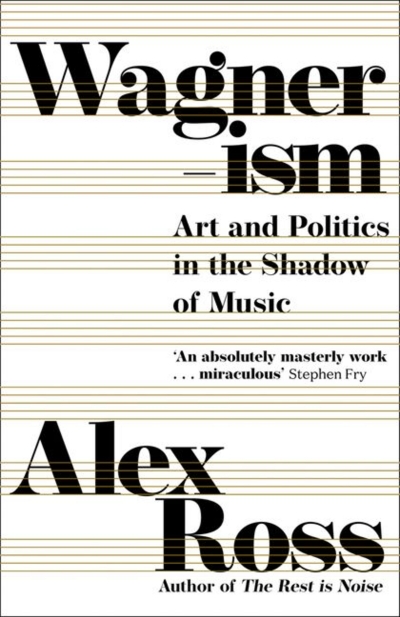

... (read more)Wagnerism: Art and politics in the shadow of music by Alex Ross

Hooray, operatic activity in Sydney is back! Well, perhaps not quite, but performances by one of Australia’s most vibrant companies, Pinchgut Opera, occurred over the weekend. Worldwide operatic activity abruptly ceased in March when Covid-19 struck, and has only recently tentatively emerged from this enforced hibernation. Opera Australia is slated to reopen early in 2021, sooner than many other companies, while others such as the Vienna State Opera endured the frustration of resuming performances as the first wave of the pandemic subsided, only to be forced to close their doors as a second wave surged.

... (read more)The fearsome figure of Attila the Hun (406–53 CE) has always had a bad press, yet in Verdi’s opera of 1846 he emerges as the most sympathetic and nuanced character of a group of three other rather unlikeable, two-dimensional principals, all of whom plot his final demise. During the course of the opera, Attila emerges as a somewhat naïve, trusting character, and shows great respect for his avowed enemy, the Roman general Ezio. Yet it does not end happily for Attila, ultimately done in by the three of them; almost certainly not a historically accurate depiction.

... (read more)