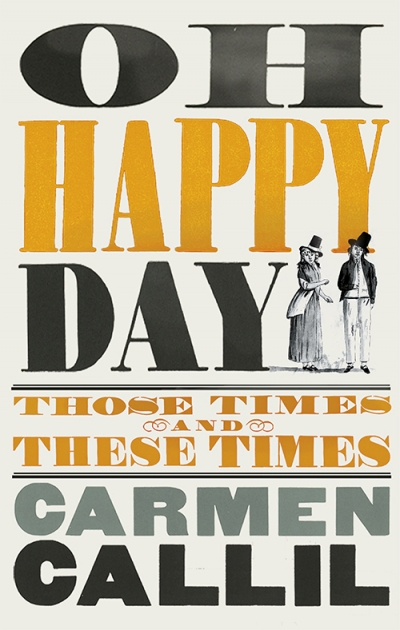

Jonathan Cape

A Life of Picasso: The minotaur years, 1933–1943 by John Richardson

More Than I Love My Life by David Grossman, translated by Jessica Cohen

What distinguishes graphic novels (aka ‘big fat comic books’) from other books is how completely the page registers movements of the maker’s hand. Before we begin the business of reading, we look, and what we see is not margin-to-margin Helvetica or Times New Roman: it’s the mark of the makers, be it Alison Bechdel or Kristen Radtke or Mandy Ord. We might even think of the making of comic books as being closer to letter writing than novel writing. Accustoming ourselves to the style of a particular graphic novelist (‘Aha! That’s how Bechdel depicts euphoria!’) is a large part of the pleasure of reading comics – the business of aligning one’s own visual point of view with the maker’s. Perhaps this is why autobiographical works have been such a vital force behind the rebirth of comic books as ‘graphic novels’.

... (read more)