War

From the Trenches: The Best Anzac Writing of World War One edited by Mark Dapin

by Geoff Page •

Christine Piper is the winner of the 2014 Calibre Prize for an Outstanding Essay, worth $5,000. In this powerful essay, she writes about Japanese biological weapons and wartime experiments on living human beings.

... (read more)Hanoi's War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam by Lien-Hang T. Nguyen

by Robert O'Neill •

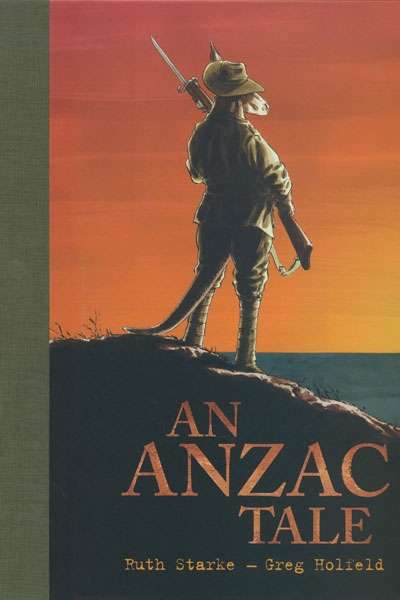

Depicting war in a picture book requires a deft hand. Historical imperatives need to be considered, while also avoiding glorifying war for a young and impressionable audience. Ideally, such books should promote informed discussion rather than mindless militarism.

... (read more)Loving This Planet by Helen Caldicott & Waging Peace by Anne Deveson

by Gillian Terzis •

Australian War Memorial: Treasures from a Century of Collecting by Nola Anderson

by Geoffrey Blainey •

Exit Wounds: One Australian’s War on Terror by John Cantwell with Greg Bearup

by Nicholas Hordern •