Anwen Crawford

Anwen Crawford is the author of No Document (Giramondo, 2021), shortlisted for the 2022 Stella Prize, and Live Through This (Bloomsbury, 2015). Her work has appeared in publications including The Monthly, The New Yorker, The White Review and Sydney Review of Books, and in 2021 she won the Pascall Prize for Arts Criticism. She is a long-time zine maker and collaborative visual artist. She lives in Sydney.

BlacKkKlansman begins with Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939), picking her way through a mire of injured Confederate soldiers. Then it cuts to Alec Baldwin as a fictional mid-twentieth-century eugenicist spewing racist pejoratives and bilge about ‘the International Jewish Conspiracy’. Footage from D.W. Griffith’s profoundly racist and egregiously influential film ... (read more)

The sky is a wintry grey when Ronit (Rachel Weisz), a photographer, arrives in London, recalled to her hometown from New York by the death of her father, a local rabbi. The Orthodox Jewish community to which she returns dresses sombrely, in shades of black, and comports itself strictly. Dovid (Alessandro Nivola), a childhood friend and her father’s protégé, steps away from Ronit when, impulsiv ... (read more)

BPM, or 120 battements par minute, to give its more expansive French title, is not the first film to be made about the charismatic activist group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP, but it is the most lyrical piece of cinema so far to have emerged from ACT UP’s history. ACT UP, founded in New York, in 1987, has long been recognised for its direct actions – occupying the Ne ... (read more)

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless is a cold, despairing film, befitting its title. It opens and closes in the depths of winter, with wide, lingering shots of an ice-bound river; in between, it delivers a portrait of a marriage that has hardened into estrangement, with a child lost to the void that exists between his parents. No character is improved by their trials, much less redeemed. No thaw ever ... (read more)

Madnesses pile up in The Death of Stalin, too fast and too numerous to itemise. Victims of tyranny are snatched away in the dead of night, locked in basements, or pushed down staircases at Chaplinesque speed. The terms of engagement change halfway through a conversation: forbidden thoughts are now doctrine; the condemned rise again. ‘I’ve had nightmares that make more sense than this,’ lamen ... (read more)

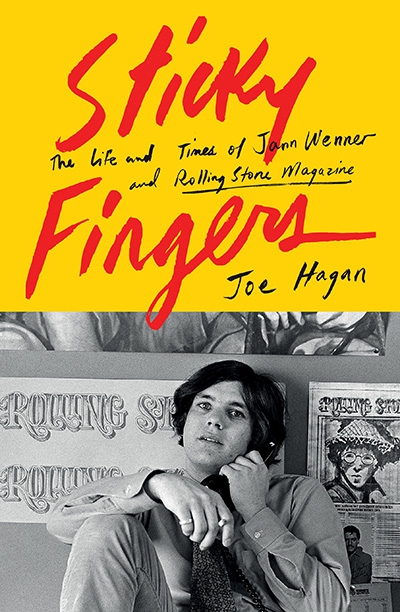

Sometime in 1970, an unidentified person – perhaps a disgruntled journalist or aggrieved interviewee – scrawled the words ‘Smash “Hip” Capitalism’ onto an office wall at Rolling Stone magazine. It was an incisive piece of graffiti. Rolling Stone had begun publishing in 1967, in San Francisco, at the epicentre of the counterculture, but it had already proved less than radical. As the re ... (read more)

Too often the suburbia on show in American movies feels like a suburbia that only exists in the movies; a fantasy land stocked with preposterously large, catalogue-neat houses populated by families that boast perfect complexions and expensive teeth. Not so in Lady Bird, set in Sacramento, California, where the glitz of Los Angeles and the fashionability of San Francisco feel very far away. Christi ... (read more)

One can pinpoint the moment at which The Killing of a Sacred Deer gets stuck, like a train between stations. It happens midway through the film, during a scene set in a hospital cafeteria, somewhere in Cincinnati. A greying, bearded cardiologist (Colin Farrell) sits opposite a teenage boy (Barry Keoghan) whose gormless, sweaty countenance conveys an undertone of menace. The boy, whose name is Mart ... (read more)

It’s springtime in Yorkshire, but you’d only know it by the lambs. The earth is stony and the wind is biting. Even the wildflowers struggle to bloom, let alone the romance that forms the central plot of God’s Own Country, an accomplished début feature from British writer–director Francis Lee, who was raised, like his film’s protagonist, on a farm in the Pennine Hills.

Johnny Saxby (Jos ... (read more)