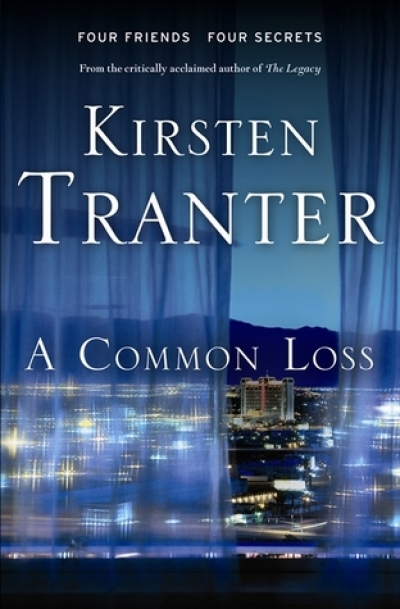

Australian Fiction

Let us take a look at this place. Marshlands. All the way to the horizon. The land drained, but nevertheless sinking. Sinking into nothing, nothing but itself. Frogs volleying noise in the grass unseen. The hazy movement of mosquitoes low to the ground. On a blade of swamp grass a sleek cricket. Blacker than night and – look closely – its antennae twitching. Just think: there must be more of those creatures, in their thousands, perhaps millions, hiding in the swamp grass as far as your eye can see.

... (read more)