Anthropology

Kin: Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose edited by Thom van Dooren and Matthew Chrulew

by Prithvi Varatharajan •

From Another Place: Migration and the politics of culture by Gillian Bottomley

by David Walker •

More Than Mere Words edited by Paul Monaghan and Michael Walsh & Ethnographer and Contrarian edited by Julie D. Finlayson and Frances Morphy

by Stephen Bennetts •

Truth’s Fool: Derek Freeman and the war over cultural anthropology by Peter Hempenstall

by Simon Caterson •

Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering ancient Australia by Billy Griffiths

by Kim Mahood •

Claude Lévi-Strauss: The Poet in the Laboratory by Patrick Wilcken

by Grant Evans •

Mothers and Others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding by Sarah Blaffer Hrdy

by Michael Gilding •

Law in a Lawless Land: Diary of a limpieza in Colombia by Michael T. Taussig

by Stephen Muecke •

The Culture Cult: Designer tribalism and other essays by Roger Sandall

by Patrick Wolfe •

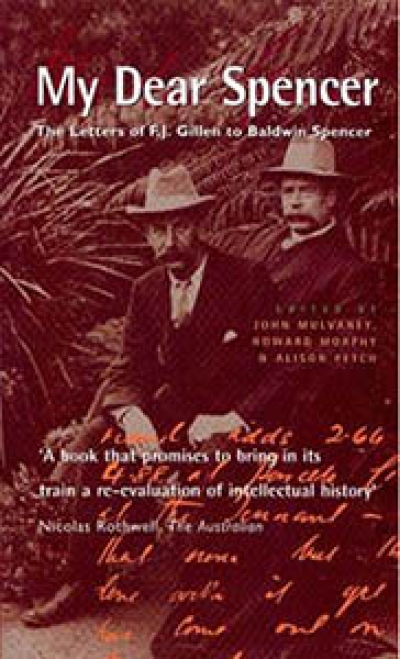

My Dear Spencer: The letters of F. J. Gillen to Baldwin Spencer edited by John Mulvaney, Howard Morphy, and Alison Petch

by Barry Hill •