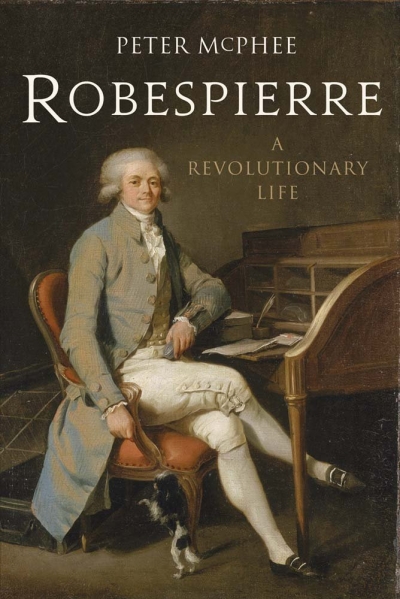

The ‘good’ biographer always opts for a nuanced portrait, and this is what Peter McPhee has given us in his well-written, reflective, sympathetic account of one of the most enigmatic, complex leaders of the French Revolution, Maximilien Robespierre (1758–94). McPhee had his work cut out for him. Those familiar with the period may come to this book, as I did, with somewhat preconceived ideas. Robespierre conjures up a rather distasteful character, a revolutionary with all the negative connotations that word can conjure: a zealot, cold, calculating, idealistic, paranoid, the prototype of the totalitarian bureaucrat capable of sending friends and colleagues to the guillotine for the ‘cause’. So I was curious as to what McPhee, a leading historian of the French Revolution, made of the man, and how he accounted for Robespierre’s condemnation to death of so many people.

...

(read more)