World War I

Hell-Bent: Australia’s leap into the Great War by Douglas Newton

by Carolyn Holbrook •

Crucible: An Australian First World War novel by J.P. McKinney

by Rodney Hall •

From the Trenches: The Best Anzac Writing of World War One edited by Mark Dapin

by Geoff Page •

Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War by Joan Beaumont

by Marilyn Lake •

Australian War Memorial: Treasures from a Century of Collecting by Nola Anderson

by Geoffrey Blainey •

Boredom is the Enemy: The Intellectual and Imaginative Lives of Australian Soldiers in the Great War and Beyond by Amanda Laugesen

by Craig Wilcox •

Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History edited by Craig Stockings

by Robin Prior •

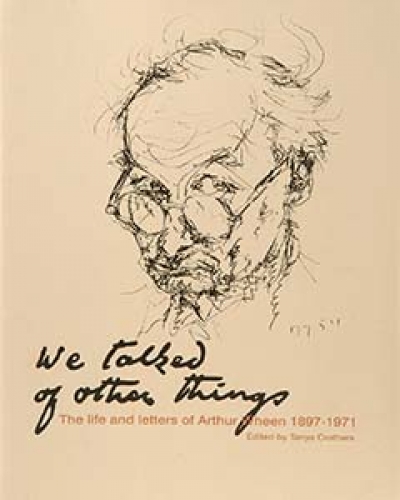

We Talked of Other Things: The life and letters of Arthur Wheen 1897–1971 edited by Tanya Crothers

by Graeme Powell •