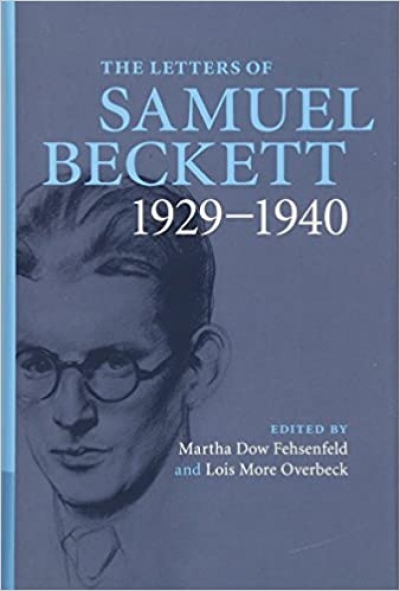

Samuel Beckett

Parisian Lives: Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir and me by Deirdre Bair

The fact that two of Australia’s major theatre companies are performing Endgame concurrently is, one hopes, merely a coincidence and not a reflection on the national Zeitgeist, for the play is one of the bleakest works in Samuel Beckett’s not exactly sunny canon. If Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot cling desperately to some hope, their co ...

Endgame. The title evokes that moment in chess when few pieces are left on the board, when the end is nigh but neither player can be confident of victory; the sense of an ending looms, but any hope of catharsis or resolution feels indulgent and premature – futile even. When the first w ...

With aching feet, bursting bladders, and the odd carrot for sustenance, Samuel Beckett’s famous pair of tramps have shuffled on to the stage of the Sydney Theatre for an extended run, though run is hardly the apposite word for this stationary duo. Perhaps one could call it an extended slump.

... (read more)