Miegunyah Press

With Love and Fury edited by Patricia Clarke and Meredith McKinney & Portrait of a Friendship edited by Bryony Cosgrove

by Lisa Gorton •

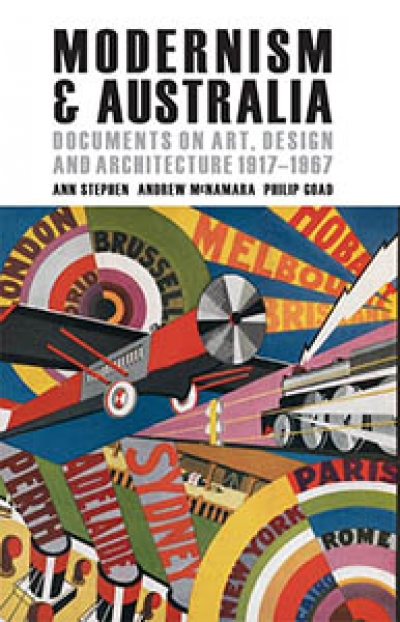

Modernism & Australia: Documents on art, design and architecture 1917–1967 edited by Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, and Philip Goad

by Anthony White •

B.A. Santamaria: Your most obedient servant: Selected Letters 1938–1996 edited by Patrick Morgan

by Brenda Niall •

Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land by Donald Thomson, edited by Nicolas Peterson

by John Mulvaney •

The Global Reach of Empire: Britain’s maritime expansion in the Indian and Pacific oceans, 1764–1815 by Alan Frost

by Donna Merwick •

Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines by David Unaipon, edited and introduced by Stephen Muecke and Adam Shoemaker

by Susan Hosking •

Colonial Consorts: The wives of Victoria’s governors, 1839–1900 by Marguerite Hancock

by Paul de Serville •

The Solitary Watcher: Rick Amor and his art by Gary Catalano

by Bernard Smith •