Daniel Thomas

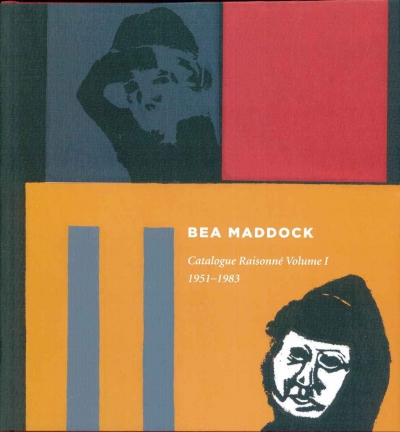

Bea Maddock: Catalogue Raisonné Volume I 1951–1983 edited by Daniel Thomas

David Walsh is a tease; he enjoys wordplay. The founder and owner of the Museum of Old and New Art (he prefers Mona, not MONA) concedes that his private playground is entirely a matter of self-gratification, like ‘the sin of Onan’. Hence the cheeky titles ‘Monanism’ for his inaugural exhibition of some 460 works, and Monanisms for the beautifully pr ...

DIAMETRIC OPPOSITES

Dear Editor,

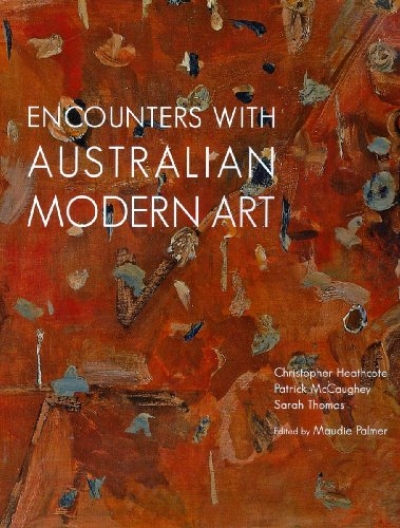

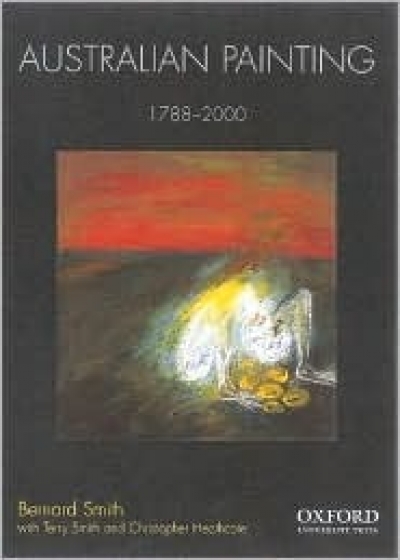

I concur with Daniel Thomas’s high opinion of the collection of Eva and Marc Besen and of their TarraWarra Museum, and share his admiration of the essays by Christopher Heathcote and Sarah Thomas in his review of Encounters with Australian Modern Art (February 2009).

...Encounters with Australian Modern Art by Christopher Heathcote, Patrick McCaughey and Sarah Thomas

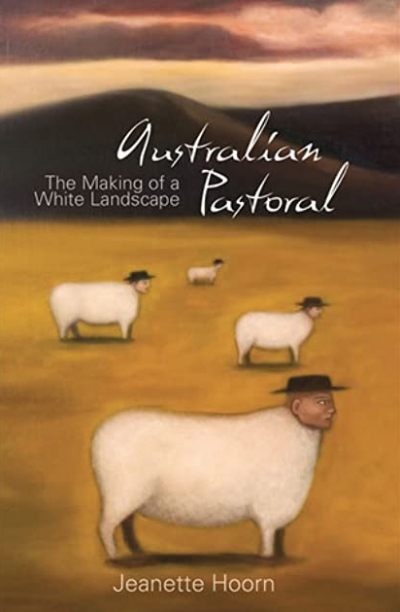

Australian Pastoral: The making of a white landscape by Jeannette Hoorn

The art collections are the main thing in an art museum, not the special exhibitions or other programs necessary for present-day credibility and fundraising. Special exhibitions can be easy fast-food showbiz, or else they can be too authoritarian, over-theorised, and bullying. Collections, the bigger the better, are where you can drop in, any day of the year, for a bit of reinvention. It’s good to choose your own pace when you want to get out of yourself .

... (read more)