University of Chicago Press

Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge by Jean-Noël Jeanneney (trans. Teresa Lavender Fagan)

by Colin Nettelbeck •

J.M. Coetzee And The Ethics Of Reading: Literature in the event by Derek Attridge

by Sue Thomas •

Threads of Life: Autobiography and the will by Richard Freadman

by David McCooey •

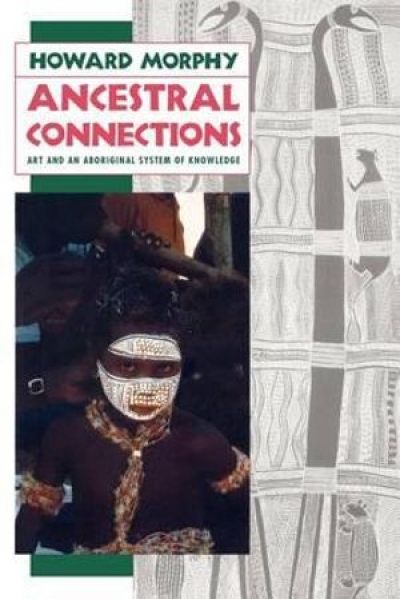

Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge by Howard Morphy

by Tim Rowse •