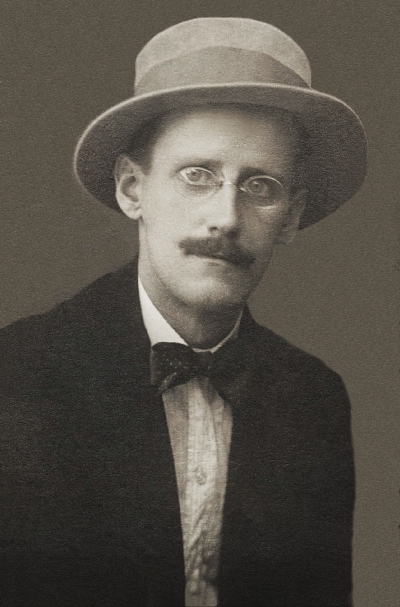

James Joyce

In this week’s ABR podcast, listen to Ronan McDonald discuss one hundred years of James Joyce’s Ulysses, among the most famous books of the twentieth century.

... (read more)The Cambridge Centenary Ulysses: The 1922 text with essays and notes by James Joyce, edited by Catherine Flynn

Consuming Joyce by John McCourt & One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses edited by Colm Tóibín

The Most Dangerous Book: The battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses by Kevin Birmingham

It’s usually said that Australians are uninterested in the metaphysical. Where in America the lines between the secular and religious are notoriously blurred, not least in their politicians or sporting heroes invoking God on almost every conceivable occasion, Australians by contrast are held to be a godless lot, their mythologies entirely secular in form and meaning. God is rarely publicly invoked, except by ministers of religion whose particular business it is duly to do so.

... (read more)If James Joyce had ever visited Australia it is unlikely that he would have come up with anything like D.H. Lawrence’s Kangaroo. For one thing, as with most Irishmen, his interest in landscape was negligible; for another, his sense of play and his myopia would not have allowed him to romanticise the great Australian bush, much Jess the suburban sprawl. He might have felt somewhat at ease in the ‘Loo or the Rocks area, in Gertrude Street, Fitzroy or Little Dorritt Street in Carlton, or perhaps by the Yarra at Burnley. But why fantasise?

... (read more)