Obituary

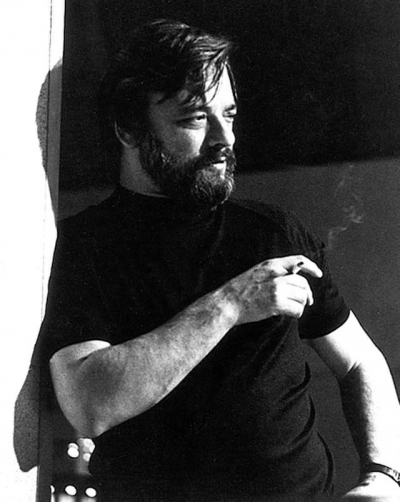

I’ve often wondered what it would be like to witness the extinguishing of a genius who not only defined an era or a movement but also ruptured an art form. Virtually nothing of Shakespeare’s death is recorded, so we are left to invent the dying of that light. Mozart’s funeral was infamously desultory, and Tolstoy’s swamped by paparazzi as much as by the peasantry. Stephen Sondheim, the single greatest composer and lyricist the musical theatre has ever known, died at his home in Connecticut on 26 November, and we who loved him feel the loss like a thunderbolt from the gods. Not because we’re shocked – he was ninety-one after all – but simply because we shall not see his like again.

... (read more)An occasion like this teaches us that we each have our own Helen Daniel. I met my Helen nearly ten years ago, appropriately through writing. I had written a book on the Aztecs of Mexico. It was primarily an academic book, but because it was published by a university press with a branch here, and because Aztecs are Aztecs, it was widely reviewed in this country. The material was esoteric and its interpretation involved some complicated talk about theoretical issues in anthropology and history, so I was relieved when the local reviews were kind. Nevertheless, I read them with mixed feelings: how was it possible for people to understand the same printed pages so variously?

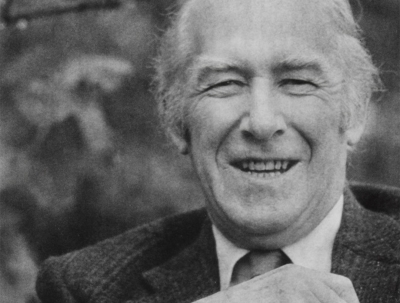

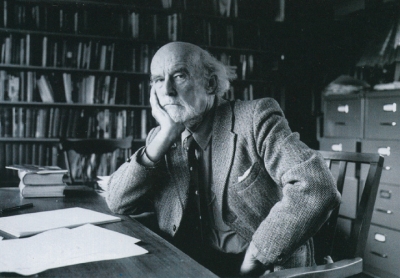

... (read more)As physical as he was metaphysical, his playful courtesy equal to his reflectiveness, Alec Hope has mortally gone from us now. In his time, which was far from short, he was like nobody else in our literary landscape. Coming from an age in which subject matter mattered, Hope became a poet of astonishingly wide range, as of remarkable intensity. His burning star has been clouded a little in recent decades because of his investment in masculine sexuality, but he survives powerfully: sometimes hilariously. We won’t forget his Red Riding Hood devouring the wolf. Among his recent forebears, he rejoiced in Baudelaire, Yeats, and early Auden, the latter an overpowering figure when the young Australian sailed to Oxford.

T.S. Eliot’s brand of juxta-positional modernism meant little to Alec, who found it all a bit shifty, but he did share the St Louis master‘s ideas about poetic impersonality: a poem was the Ding an sich, not the shadow of its writer within it. Once, indeed, he poked mullock at Eliot by citing his putative play, Merd, or In the Cathedral.

... (read more)Dear Elizabeth,

Well, it seems our long correspondence is over. Actually it ended some years ago, didn’t it? Your last letter to me is dated Christmas Eve 2001. I continued writing to you into the following year, not immediately realising you were unable to reply, even though your later letters spoke of confusion and of unaccountably getting lost in familiar streets.

... (read more)Helen Daniel, the editor of Australian Book Review since 1995, died suddenly on Monday, 16 October 2000. Her death has sent waves of shock and sorrow throughout the Australian literary world. According to Andrew Riemer, at the Writers’ Week in Brisbane, held on the weekend after Helen’s death, session after session paid homage to this woman who, without vanity or arrogation, had made her name synonymous with the profession and apprehension of Australian literature.

Her death diminishes all of us. It’s strange to reflect that Helen, who occupied her position so quietly (at times so stoically) was in fact far and away the greatest champion for Australian writing in her generation and that her time as a critic and editor coincided with the great efflorescence of Australian publishing that we now wonder at and ponder.

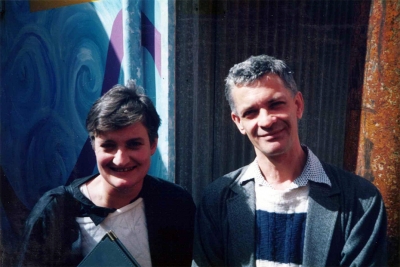

... (read more)Frank Graham Little was born in Belfast 1 November 1939 and died Melbourne 24 February 2000. He spoke quietly and literally made a profession of observation, of seeing through and beneath human behaviour, so could appear passive. He was not. He was a man who took hold of his life, and was absolutely in the middle of yet another intellectual adventure when he died suddenly last month.

... (read more)Geoff Dutton was a man-of-letters who for many years made (with Max Harris) Adelaide seem one of the lively centres of Australian literary culture. One thinks of him in association with the magazines Angry Penguins, Australian Letters, and the original Australian Book Review, not to mention the inauguration of an Australian publication list for Penguin Books, and then, when that soured, the setting up of Sun Books, one of the most innovative of Australian publishing ventures at that time – which was in the difficult slough period of the 1950s and 1960s and into the 1970s.

... (read more)Despite the importance of her poetry and prose, Oodgeroo’s experiences were much more than a catalogue of achievements in European terms. Her life, often hard fought, was one of enjoyment as well as pain, of laughter as well as sorrow. Oodgeroo had a wonderful sense of humour; it was, like the title of Ruby Langford’s latest book, ‘real deadly’. She was always able to use this to advantage, to embarrass stuffy politicos, to get action, to explode stereotypes of Aboriginal people. At the same time, she related to young people better than anyone else I have ever met. She told stories, she entertained, she challenged and always threw down the gauntlet. I’ll never forget the day she was involved in a radio hook-up with children from all over Queensland and was coaching aspiring young poets over the phone: ‘That’s a great piece – now you keep writing! Never forget; you do what your teachers say, because knowledge is power. Now, go out and get some!’

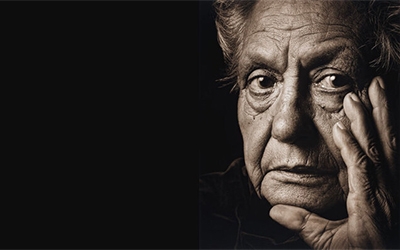

... (read more)On 27 May, 1991, Manning Clark, Australian historian extraordinary, was buried from Canberra’s Roman Catholic cathedral by his friend the Jesuit Dr John Eddy, assisted by Professor Clark’s brother, an Anglican canon, and with the participation of his sons. After his death on 23 May, ABC national television had broadcast an interview of 1989 in which Clark had responded to the question of whether he believed in an afterlife with a firm no – to which he added that he saw merit in the response of a Mexican academic encountered twenty years before. On that matter, he harboured ‘a shy hope’. It is a smiling happy phrase, contrasting with the dark fear of future judgement that bedevils so many of the Protestant characters with which he populates his histories. And it was a qualification in harmony, not only with his occasional visits to the church that farewelled him, and earlier St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney and a multitude of European churches, but also with the ambivalence and perplexity at the heart of the man and his work. Some would call it contradiction or even evasion, but the native Australian sense of having a bob each way is sound policy, and Manning was not one for some pointless cremated affirmation of the kingdom of nothingness when he could have a touch of Catholic ritual and grandeur.

... (read more)Arthur Phillips, who died last month at the age of eighty-five, was one of the major figures of the democratic nationalist tradition in modern Australian literary criticism; and his collection of essays, The Australian Tradition (1958; second edition 1966) epitomises the strength of this school. These essays are marked by the perception of the reading behind them, the clarity of the writing in them, and, the enthusiasm for his subject which shows throughout them.

... (read more)