Culture

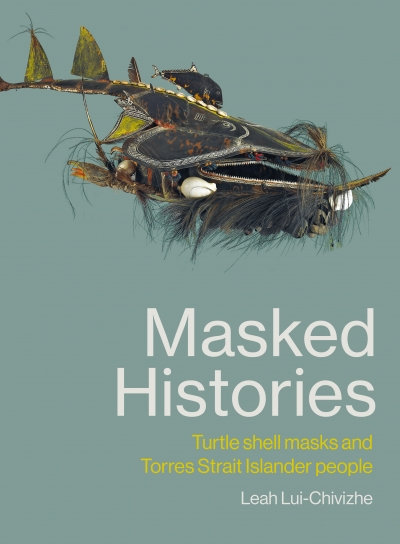

Masked Histories: Turtle Shell Masks and Torres Strait Islander People by Leah Lui-Chivizhe

by Ben Silverstein •

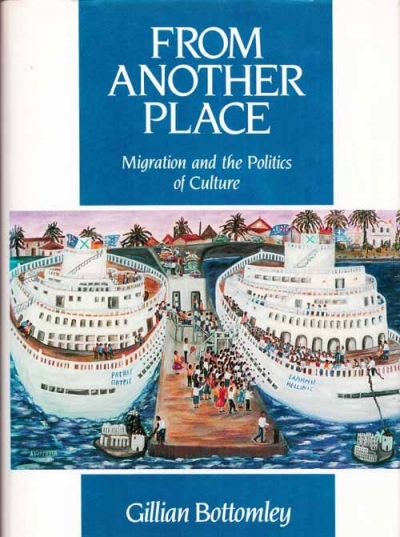

From Another Place: Migration and the politics of culture by Gillian Bottomley

by David Walker •

In the Vernacular: A generation of Australian culture and controversy by Stuart Cunningham

by Jake Wilson •

Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge by Jean-Noël Jeanneney (trans. Teresa Lavender Fagan)

by Colin Nettelbeck •

Imagining Australia: Literature and culture in the new new world edited by Judith Ryan and Chris Wallace-Crabbe

by Lisa Gorton •

The Virtual Republic: Australia’s culture wars of the 1990s by McKenzie Wark

by Gerard Windsor •

The Abundant Culture, Meaning and Significance in Everyday Australia edited by David Headon, Joy Hooton, and Donald Horne

by Humphrey McQueen •