Scribe

The Bird Way: A new look at how birds talk, work, play, parent, and think by Jennifer Ackerman

by Simon Caterson •

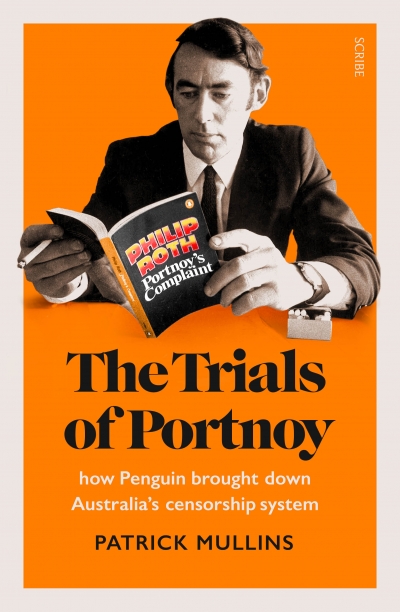

The Trials of Portnoy: How Penguin brought down Australia’s censorship system by Patrick Mullins

by James Ley •

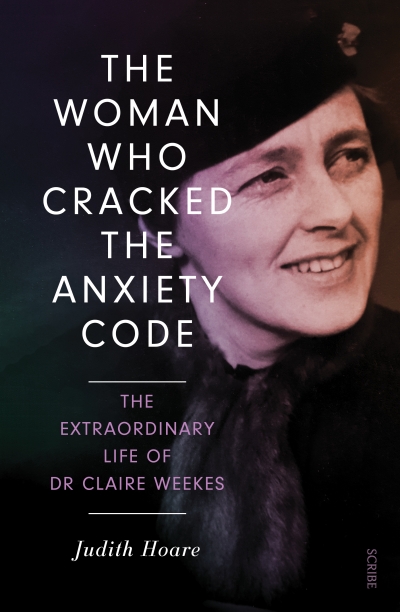

The Woman Who Cracked the Anxiety Code: The extraordinary life of Dr Claire Weekes by Judith Hoare

by Carol Middleton •

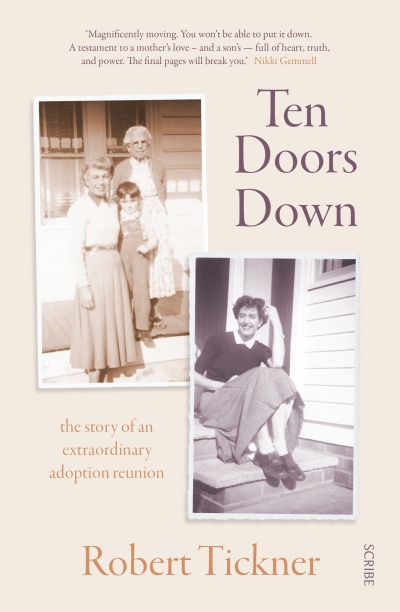

Ten Doors Down: The story of an extraordinary adoption reunion by Robert Tickner

by Joshua Black •

Waters of the World: The story of the scientists who unraveled the mysteries of our oceans, atmosphere, and ice sheets and made the planet whole by Sarah Dry

by Michael Adams •

Bank bashing is an old sport in Australia, older than Federation. In 1910, when Labor became the first party to form a majority government in the new Commonwealth Parliament, they took the Money Power – banks, insurers, financiers – as their arch nemesis. With memories of the 1890s crisis of banking collapses, great strikes, and class conflict still raw, the following year the Fisher government established the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, ‘The People’s Bank’, as a state-owned trading bank offering cheap loans and government-guaranteed deposits to provide stiff competition to the greedy commercial banks gouging its customers.

... (read more)