Allen & Unwin

In the wake of other recent compelling débuts – Paige Clark’s meticulously crafted and imagined She is Haunted being a standout – three new short story collections, varying markedly in tone, style, and setting, offer bold and unsettling visions of twenty-first-century life.

... (read more)Facts and Other Lies: Welcome to the disinformation age by Ed Coper

Australia’s Great Depression: How a nation shattered by the Great War survived the worst economic crisis it has ever faced by Joan Beaumont

The Party: The Communist Party of Australia from heyday to reckoning by Stuart Macintyre

There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen,’ Vladimir Lenin has been credited with saying, with reference to the Bolshevik Revolution. It’s a sentiment that immediately springs to mind when reading Jessica Stanley’s A Great Hope, a début that, while not billed as historical fiction, is deeply concerned with history and its making.

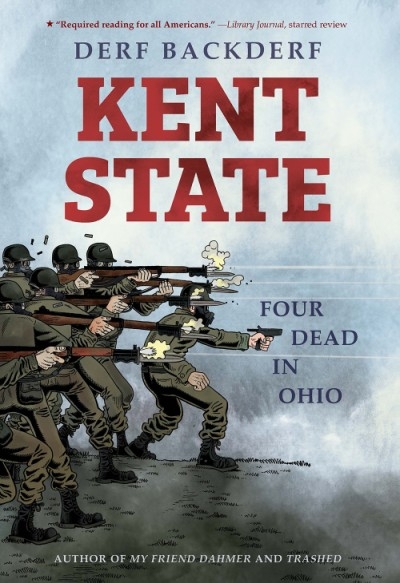

... (read more)Kent State by Derf Backderf & Underground by Mirranda Burton

Paige Clark’s She Is Haunted (Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 264 pp) opens with the story ‘Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’, a title that alludes to the five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance – that inform the rest of her début collection. Clark doesn’t explain why the narrator feels anxious about the survival of her unborn child and its father. The reader is left to assume that the prospect of too much undeserved happiness impels her to embark on a series of amusing and escalating bargains with a capricious God. That the narrator bears the losses with equanimity is indicative of the deadpan humour with which Clark deflects serious matters.

... (read more)