1996 (57)

Children categories

February–March 1996, no. 178 (1)

Welcome to the February-March 1996 issue of Australian Book Review!

December 1996–January 1997, no. 187 (2)

Welcome to the December 1996-January 1997 issue of Australian Book Review.

November 1996, no. 186 (0)

Welcome to the November 1996 issue of Australian Book Review.

October 1996, no. 185 (0)

Welcome to the October 1996 issue of Australian Book Review.

September 1996, no. 184 (0)

Welcome to the September 1996 issue of Australian Book Review.

The good old days (bad old days?) of young adult fiction are gone. A couple of decades back it was impossible to imagine a reputable mainstream publisher producing a book for older children which has been supported by the Literature Board of the Australia Council and whose plot revolves around drug-taking (casual and accepted), violence, murder, abduction and rape. This is what The Enemy You Killed is about. The question is, does it more accurately depict real life than, say, an old-fashioned genteel novel like Swallows and Amazons? Perhaps it depends where you live. I’m not convinced that teenage gunplay with live ammunition is necessarily more ‘real’ than messing about with boats. At least in Australia. There is more than a whiff of the tabloids around the melodrama of The Enemy You Killed. It tells of a fifteenyear-old girl, Jules (Julia), who lives in an unspecified country town which lies close to a state forest dissected by a steep gorge. In this forest, mostly at weekends, many of the local young people have for many years been playing wargames dressed in combat gear and using not only air rifles and home-made explosives, but sometimes real combat weapons. The Tunnel Rats stalk The Rebels and vice versa, and a successful ambush is the ultimate thrill.

Jules has an oppressive past. When she learned some time back that she was adopted, she freaked, and hid out in the local hotel as a groupie with a heavy metal band before finally returning home. Then she formed a relationship with cold-eyed, unruffled bad boy Wade,

before finally getting her act together and finding happiness in dumping him for sexy Jammo, boxing champion and hunk. Jammo is the most successful leader the Tunnel Rats have had; Wade’s speciality is to act as the lone sniper.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Reviews

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Guns, No Roses

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

The good old days (bad old days?) of young adult fiction are gone. A couple of decades back it was impossible to imagine a reputable mainstream publisher producing a book for older children which has been supported by the Literature Board of the Australia Council and whose plot revolves around drug-taking (casual and accepted), violence, murder, abduction and rape. This is what The Enemy You Killed is about. The question is, does it more accurately depict real life than, say, an old-fashioned genteel novel like Swallows and Amazons? Perhaps it depends where you live. I’m not convinced that teenage gunplay with live ammunition is necessarily more ‘real’ than messing about with boats. At least in Australia. There is more than a whiff of the tabloids around the melodrama of The Enemy You Killed. It tells of a fifteenyear-old girl, Jules (Julia), who lives in an unspecified country town which lies close to a state forest dissected by a steep gorge. In this forest, mostly at weekends, many of the local young people have for many years been playing wargames dressed in combat gear and using not only air rifles and home-made explosives, but sometimes real combat weapons. The Tunnel Rats stalk The Rebels and vice versa, and a successful ambush is the ultimate thrill.

- Book 1 Title The Enemy You Killed

- Book Author Peter McFarlane

- Book 1 Author Type Author

- Display Review Rating No

Jeffrey Grey reviews 'The Empire Fractures: Anglo-Australian Conflict in the 1940s' by Christopher Waters

Written by Jeffrey GreyThe central contention of this provocative, well-written, and extensively researched study is that Australia underwent a process of decolonisation during the 1940s, and that only by understanding this can we make sense of the subsequent relationships between Australia, Britain and the United States.

The wartime reorientation of Australian affairs away from Britain and towards the United States was viewed as a purely wartime expedient, and even before the war’s end the Australian government (a Labor government, let it be remembered), was looking to renewing the military and diplomatic ties with Britain which the Pacific war had weakened. The election of Attlee’ s government in Britain in 1945 brought with it expectations that a grouping of Labour governments in the Dominions would prove a positive force in remaking Commonwealth relations in the postwar era. The British Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, jokingly referred to a meeting of the Commonwealth prime ministers in 1946 as the ‘Imperial Labour Executive’.

It was not to be, and in the field of foreign relations in particular the Australian and British governments found it increasingly difficult to reach agreement or act to a common purpose across a range of issues in the second half of the 1940s. The two overriding issues of postwar history – decolonisation of the European empires and the East-West tensions which rapidly developed into a state of Cold War – emerged early, and agreement between Australia and Britain on either proved impossible, at least until 1949.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Politics

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Fractured Empire

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

The central contention of this provocative, well-written, and extensively researched study is that Australia underwent a process of decolonisation during the 1940s, and that only by understanding this can we make sense of the subsequent relationships between Australia, Britain and the United States.

- Book 1 Title The Empire Fractures

- Book 1 Subtitle Anglo-Australian Conflict in the 1940s

- Book Author Christopher Waters

- Book 1 Biblio Australian Scholarly Publishing, $34.95 pb, 269 pp

- Book 1 Author Type Author

- Display Review Rating No

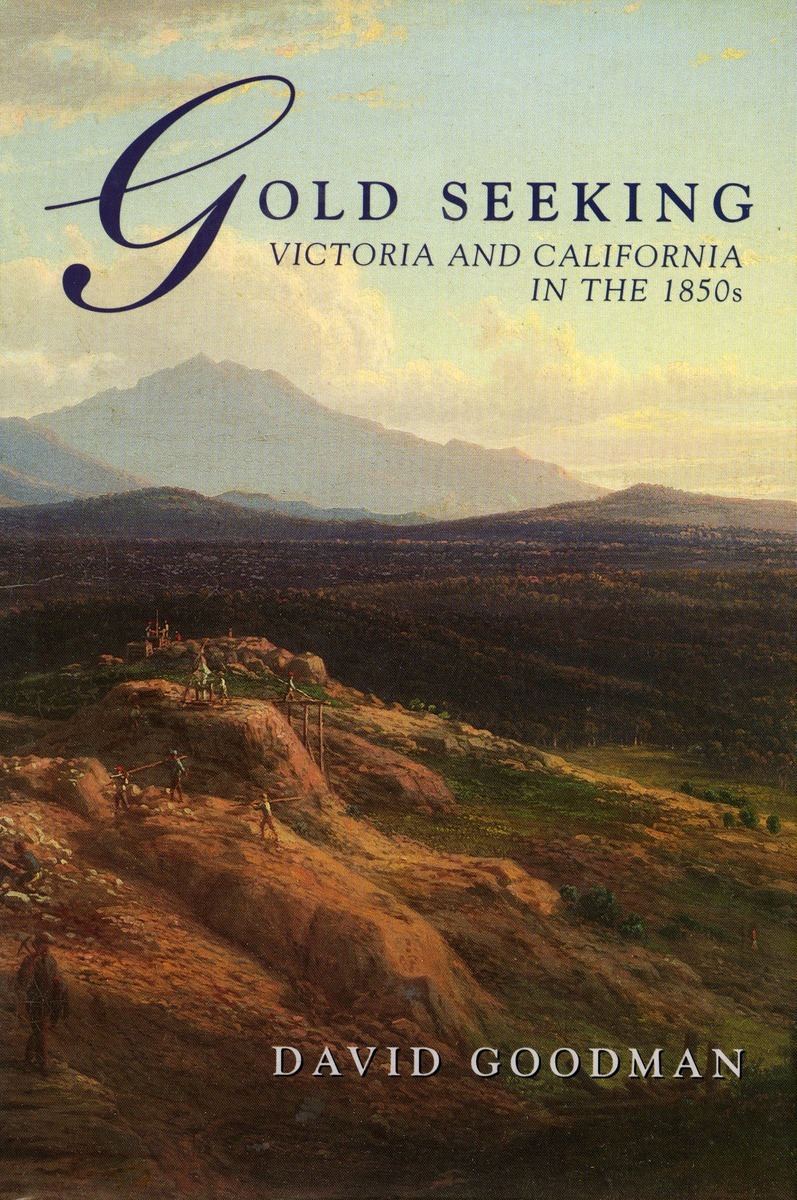

The first virtue of this study is to remind us of the dramatic, potentially cataclysmic, quality of the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes to California in the late 1840s and to south-east Australia soon afterwards. That was prime among the several characteristics the two experiences had in common. At few other points is there so close affinity in the histories of Australia and the USA. The subject is altogether appropriate for one, like David Goodman, who has engaged in research in both countries, and who teaches their comparative history. The result is a most satisfying monograph. While the heavier incidence is on the Australian side, this is one of the few examples in the Australian repertoire of effective comparative work. One of few others in that list – Andrew Markus’s Fear and Hatred – also probes the goldfield, experience, describing how the British master-race treated the Chinese in either case. Goodman’ s aim is much more ambitious – to reveal basic socio-political responses to the cataclysm of gold.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category History

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title The Cataclysm of Gold

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

The first virtue of this study is to remind us of the dramatic, potentially cataclysmic, quality of the mid-nineteenth century gold rushes to California in the late 1840s and to south-east Australia soon afterwards. That was prime among the several characteristics the two experiences had in common. At few other points is there so close affinity in the histories of Australia and the USA. The subject is altogether appropriate for one, like David Goodman, who has engaged in research in both countries, and who teaches their comparative history. The result is a most satisfying monograph. While the heavier incidence is on the Australian side, this is one of the few examples in the Australian repertoire of effective comparative work. One of few others in that list – Andrew Markus’s Fear and Hatred – also probes the goldfield, experience, describing how the British master-race treated the Chinese in either case. Goodman’ s aim is much more ambitious – to reveal basic socio-political responses to the cataclysm of gold.

- Book 1 Title Gold Seeking

- Book 1 Subtitle Victoria and California in the 1850's

- Book Author David Goldman

- Book 1 Biblio Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 302 pp

- Book 1 Author Type Author

-

Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600)

-

Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200)

- Display Review Rating No

Letters to the Editor - April 1996

Written by Hidden AuthorDear Editor,

I am flabbergasted at the savage, totally unjustified hatchet job that Richard Hall has done on Hugh Mackay in the National Library Voices Essay (ABR, Feb/March 1996). Is the National Library now paying for character assassination?

I know both Hugh Mackay and Richard Hall. I think that the Pot should always think carefully before calling the Pan sooty-arse. If Mr Mackay looks like ‘a possum thinking about an apple’, the curmudgeonly Mr Hall looks a bit like the possum’s bum.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Letters

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Letters

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Dear Editor,

I am flabbergasted at the savage, totally unjustified hatchet job that Richard Hall has done on Hugh Mackay in the National Library Voices Essay (ABR, Feb/March 1996). Is the National Library now paying for character assassination?

I know both Hugh Mackay and Richard Hall. I think that the Pot should always think carefully before calling the Pan sooty-arse. If Mr Mackay looks like ‘a possum thinking about an apple’, the curmudgeonly Mr Hall looks a bit like the possum’s bum.

- Display Review Rating No

Kristin Hammett reviews 'Marilyn's Almost Terminal New York Adventure' by Justine Ettler

Written by Kristin HammettMarilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure offers all the ingredients that have made Justine Ettler’s name to date: sex, drugs, tough women, bad men, and rough prose. Thankfully it does leave behind some, though not all, of the relentless violence of The River Ophelia. Marilyn is not as hell-bent on the same masochistic path as Ettler’s earlier heroine, Justine, and the novel admits a lightness of tone which is initially refreshing.

‘This story about Marilyn’, the narrator informs us,

doesn’t start with her moderately immaculate conception or with her depraved adolescence ... or with that summer she spent clinging to a bobbing beyond-the-breakers surfboard off Australia’s most famous beach and squeezed orgasm after orgasm from between her tanned teenager’s thighs.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Fiction

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title A New Justine?

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Marilyn’s Almost Terminal New York Adventure offers all the ingredients that have made Justine Ettler’s name to date: sex, drugs, tough women, bad men, and rough prose. Thankfully it does leave behind some, though not all, of the relentless violence of The River Ophelia. Marilyn is not as hell-bent on the same masochistic path as Ettler’s earlier heroine, Justine, and the novel admits a lightness of tone which is initially refreshing.

- Book 1 Title Marilyn's Almost terminal New York Adventure

- Book Author Justine Ettler

- Book 1 Biblio Picador, $14.95, 254pp

-

Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600)

- Display Review Rating No

Edward Colless is the ‘don’ of the art world – in fact, he is Juan, Quixote, and Giovanni all woven together. The Error of My Ways is his ‘mille e tre’ of theoretical affairs – essays and articles that have infected an otherwise sterile art scene with a flame of desire.

The catalogue essay is a sadly neglected craft. Every week, art galleries commission hundreds of short essays to accompany images in their exhibition catalogues. The quality of these essays range from testimonies by an artist’s mate, theoretical exegesis, and creative musing. Regardless of quality, their destiny appears as ephemeral as the shows they illuminate. That such a mass of writing should be consigned to oblivion is disheartening for those in the trade, which is reason to welcome the decision by Brisbane’s IMA to publish a collection of essays by the best catalogue essay writer in the country. The enigmatic style of Colless emerged in the early 1980s, along with art theory publications such as On the Beach and Paul Taylor’s Art and Text. While many of his colleagues have since moved to fresh pastures in Cultural Studies, Colless migrated to Hobart. Judging from the sample of forty-six essays included in The Error of My Ways, Hobart has insulated this writer from the cults of contemporaneity that flourish on the mainland.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title The Error of My Ways

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Edward Colless is the ‘don’ of the art world – in fact, he is Juan, Quixote, and Giovanni all woven together. The Error of My Ways is his ‘mille e tre’ of theoretical affairs – essays and articles that have infected an otherwise sterile art scene with a flame of desire.

- Book 1 Title The Error of My Ways

- Book Author Edward Colless

- Book 1 Biblio Institute of Modern Art Brisbane, $19.95 pb, 233 pp

- Display Review Rating No

It is always a pleasure to read Glenda Adams, a most accomplished and stylish writer. At its best her work displays a natural and unassuming flow, masking artistry of a high order. Admirers of her earlier books will find many familiar concerns in The Tempest of Clemenza; they will also discover her striking out in new directions in a bold and adventurous undertaking.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Fiction

- Custom Article Title Adams' Gothic

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Adams' Gothic

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

It is always a pleasure to read Glenda Adams, a most accomplished and stylish writer. At its best her work displays a natural and unassuming flow, masking artistry of a high order. Admirers of her earlier books will find many familiar concerns in The Tempest of Clemenza; they will also discover her striking out in new directions in a bold and adventurous undertaking.

- Book 1 Title The Tempest of Clemenza

- Book Author Glenda Adams

- Book 1 Biblio Angus and Robertson, $24.95 hb, 299 pp

-

Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600)

-

Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200)

- Display Review Rating No

Thérèse Radic reviews 'Playing the Past', edited by Kerry Kilner and Sue Tweg, 'The Gap' by Anna Broinowski, and 'The History of Water' by Noëlle Janaczewska

Written by Thérèse RadicKatherine Brisbane’s Currency Press is the major play-publishing house in the country and no stranger to the snap-freeze process of producing program play texts by women as well as men. The women have a fair representation in Currency’s general range, but they proliferate in the Current Theatre Series, those pre-first production texts so impossible to follow up with the writer’s post-natal reconsiderations.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Theatre

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Five plays by women

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Katherine Brisbane’s Currency Press is the major play-publishing house in the country and no stranger to the snap-freeze process of producing program play texts by women as well as men. The women have a fair representation in Currency’s general range, but they proliferate in the Current Theatre Series, those pre-first production texts so impossible to follow up with the writer’s post-natal reconsiderations.

- Book 1 Title Playing the Past

- Book Author Kerry Kilner and Sue Tweg

- Book 1 Biblio Currency, $10 pb, 54 pp

- Book 1 Author Type Editor

- Book 2 Title The History of Water

- Book 2 Author Noëlle Janaczewska

- Book 2 Biblio Currency, $14.95 pb, 56 pp

-

Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600)

- Display Review Rating No

'Editorial' by Helen Daniel

Written by Helen DanielIn this issue, Hugh Mackay replies to Richard Hall’s essay in last month’s issue and his reply is printed here in full, unedited, at his insistence – which was communicated to me by his lawyers. As a matter of principle, of course, ABR offers right of reply, which is indeed a regular feature of the magazine, most commonly through the letters to the editor. On this occasion, given Hugh Mackay’s insistence, ABR includes his 3,300-word reply as a special feature.

In his reply, which he calls a ‘rebuttal’, Hugh Mackay points out that The Mackay Reports are not ‘books’ and therefore wonders ‘why they got a run in ABR’. I am interested that Hugh Mackay appears puzzled that matters not in ‘book’ form should come into the domain of ABR.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Editorial

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Editorial

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

In this issue, Hugh Mackay replies to Richard Hall’s essay in last month’s issue and his reply is printed here in full, unedited, at his insistence – which was communicated to me by his lawyers. As a matter of principle, of course, ABR offers right of reply, which is indeed a regular feature of the magazine, most commonly through the letters to the editor. On this occasion, given Hugh Mackay’s insistence, ABR includes his 3,300-word reply as a special feature.

In his reply, which he calls a ‘rebuttal’, Hugh Mackay points out that The Mackay Reports are not ‘books’ and therefore wonders ‘why they got a run in ABR’. I am interested that Hugh Mackay appears puzzled that matters not in ‘book’ form should come into the domain of ABR.

- Display Review Rating No

There are two reasons for celebrating this chastely elegant slim volume. One is the arrival of a publisher prepared, when major firms are retreating from the field, to declare that poetry is central to a flourishing literary culture, and to match that declaration by commitment to a new series, Brandl & Schlesinger Poetry. The other is the appearance of a new and striking collection from that fine poet Rhyll McMaster.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Poetry

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Married to Matter, Inexorably

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

There are two reasons for celebrating this chastely elegant slim volume. One is the arrival of a publisher prepared, when major firms are retreating from the field, to declare that poetry is central to a flourishing literary culture, and to match that declaration by commitment to a new series, Brandl & Schlesinger Poetry. The other is the appearance of a new and striking collection from that fine poet Rhyll McMaster.

- Book 1 Title Chemical Bodies

- Book Author Rhyll McMaster

- Book 1 Biblio Brandl & Schlesinger, $16.95pb, 75pp

- Book 1 Author Type Author

- Display Review Rating No

More...

Not another novel about heroin, you might ask. You might as well say, not another novel about addiction to anything, including love or death. Luke Davies’ novel risks being seen to jump on the bandwagon of relevance, or grunge, or whatever turns you off. But this a good book, a true book, which left me feeling sad for some days, not a bad thing in these times of numbing busyness in which many of us seem to be trapped.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Fiction

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Addictive Genre

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Not another novel about heroin, you might ask. You might as well say, not another novel about addiction to anything, including love or death. Luke Davies’ novel risks being seen to jump on the bandwagon of relevance, or grunge, or whatever turns you off. But this a good book, a true book, which left me feeling sad for some days, not a bad thing in these times of numbing busyness in which many of us seem to be trapped.

- Book 1 Title Candy

- Book Author Luke Davies

- Book 1 Biblio Allen & Unwin $16.95 pb, 286 pp

- Book 1 Author Type Author

- Book 1 Readings Link booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2r0zDM

- Display Review Rating No

Hayden: An autobiography is a fine book – one of the best political memoirs written by an Australian. It’s also a valuable historical work by a former politician who, thank God, doesn’t take himself too seriously.

Bill Hayden clearly made good use of his time as governor–general (1989–96) to undertake extensive research. In the acknowledgments section, the author gives generous thanks to librarians and archivists who assisted his endeavours. But it is clear that much of the detailed work was undertaken by Hayden himself.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Memoir

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Hayden’s Memoirs

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Hayden: An autobiography is a fine book – one of the best political memoirs written by an Australian. It’s also a valuable historical work by a former politician who, thank God, doesn’t take himself too seriously.

Bill Hayden clearly made good use of his time as governor–general (1989–96) to undertake extensive research. In the acknowledgments section, the author gives generous thanks to librarians and archivists who assisted his endeavours. But it is clear that much of the detailed work was undertaken by Hayden himself.

- Book 1 Title Hayden

- Book 1 Subtitle An autobiography

- Book Author Bill Hayden

- Book 1 Biblio HarperCollins $39.95 hb, 610 pp

- Book 1 Author Type Author

- Display Review Rating No

Almost at the end of his very long biography, Tom Roberts, Humphrey McQueen wonders why – if Australian landscape painting had so much need of a father – ‘no-one thought to install Margaret Preston as the mother’ of the genre? He has a suggestive answer to a question which needed to be posed:

That landscape art should seek a father when our culture describes nature and the earth as mothers is not a contradiction. We distinguish the given as feminine from the created as masculine. Nurturing is perceived as a passive bearing whereas men transform nature by their activities, whether ringbarking or painting.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Biography

- Review Article Yes

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Almost at the end of his very long biography, Tom Roberts, Humphrey McQueen wonders why – if Australian landscape painting had so much need of a father – ‘no-one thought to install Margaret Preston as the mother’ of the genre? He has a suggestive answer to a question which needed to be posed:

- Book 1 Title Tom Roberts

- Book Author Humphrey McQueen

- Book 1 Biblio Macmillan, $60.00 hb, 784 pp

- Display Review Rating No

Garry Disher: The Sunken Road is a so-called literary novel. I find that I’m a bit typecast, Garry Disher the crime writer or Garry Disher the children’s writer. A lot of the fiction I’ve written is so-called more literary in nature. This is my big book, up to date, if you like. It’s a novel set in the wheat and wool country in the mid-north of South Australia where I grew up. It’s a story of the region and of a family and of a main character called Anna Tolley. I tell this story in a series of biographical fragments around a theme like Christmas, or love, or hate, or birthdays. And each fragment takes a character from childhood to old age. And I repeat this pattern right through the book and certain secrets are revealed or come to the surface through this repetition. So at that level I suppose it’s a linear story, but the structure’s not all that linear. In terms of structure it’s an advance for me, or an experiment.

Additional Info

- Free Article No

- Contents Category Interview

- Subheading Extract from an interview with Garry Disher

- Review Article No

- Show Author Link Yes

- Show Byline Yes

- Article Title Extract from an interview with Garry Disher

- Online Only No

-

Custom Highlight Text

Garry Disher: The Sunken Road is a so-called literary novel. I find that I’m a bit typecast, Garry Disher the crime writer or Garry Disher the children’s writer. A lot of the fiction I’ve written is so-called more literary in nature. This is my big book, up to date, if you like. It’s a novel set in the wheat and wool country in the mid-north of South Australia where I grew up. It’s a story of the region and of a family and of a main character called Anna Tolley. I tell this story in a series of biographical fragments around a theme like Christmas, or love, or hate, or birthdays. And each fragment takes a character from childhood to old age. And I repeat this pattern right through the book and certain secrets are revealed or come to the surface through this repetition. So at that level I suppose it’s a linear story, but the structure’s not all that linear. In terms of structure it’s an advance for me, or an experiment.

- Display Review Rating No