Archive

''Tirra Lirra' and Beyond - Jessica Anderson’s truthful fictions' by Susan Sheridan

by Susan Sheridan •

‘Everyone I talk to remembers Tirra Lirra by the River as a wonderful book, sometimes even as a life-changing one. But why don’t we hear anything about it today?’ This was a young journalist who ... ... (read more)

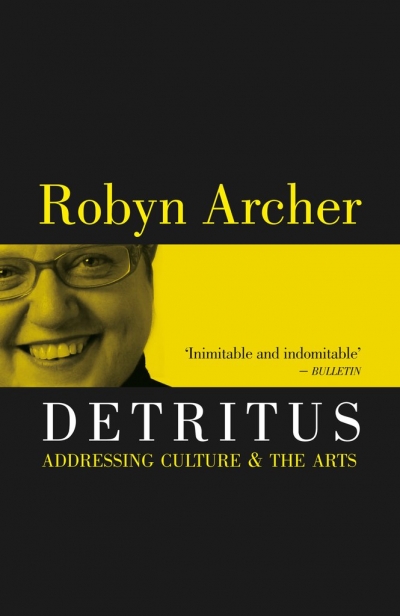

Detritus: Addressing Culture and the Arts by Robyn Archer

by Alison Broinowski •

Anzac Legacies: Australians and the Aftermath of War edited by Martin Crotty and Marina Larsson

by Alistair Thomson •