Andrea Goldsmith

Andrea Goldsmith is a Melbourne-based novelist and reviewer. Her novels include The Prosperous Thief (2002), which was short-listed for the Miles Franklin, the acclaimed Reunion, and The Memory Trap (2013), a novel of monuments, marriage, and music, awarded the Melbourne Prize in 2015. She also writes essays and articles, many of which are posted on her website.

Earlier this year, while still much occupied with our works in progress, Drusilla Modjeska and I discussed what our next projects might be. We were both tempted to put together a collection of our shorter writings – essays, talks, reviews, articles – already written and just needing a touch up. ‘Money for nothing and your books for free,’ I said, echoing the old Dire Straits song – albei ... (read more)

On a weekend when the Melbourne Age and the Australian could muster barely three book pages between them and only one review of a work of fiction, I went to an exhibition of Juan Davila’s recent work. The paintings were visceral, fierce, transgressive, shocking. Here was art disdainful of demands for beauty, art that took the notion of aesthetics into the dungeons of the mind. And it set me on e ... (read more)

More than twenty-five years ago, I wrote an essay on the work of Oliver Sacks (Island Magazine, Autumn 1993). Entitled ‘Anthropologist of Mind’, it ranged across several of Sacks’s books; but it was Seeing Voices, published in 1989, that was the main impetus for the essay. In Seeing Voices, Sacks explored American deaf communities, past and present. He exposed the stringent and often punishi ... (read more)

I heard the Egypt story countless times, but then Dorothy Porter believed that if a story was worth telling, it warranted multiple retellings. In the late 1980s, before Dot and I met, she visited Egypt to gather material for her verse novel Akhenaten (1992). In Cairo, she joined a tour group taking in the major historical sights. Dot was, by this time, steeped in the life and times of the visionar ... (read more)

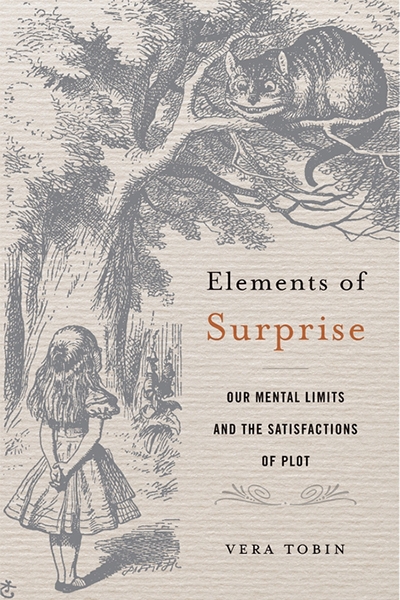

On the dust jacket of Elements of Surprise is the well-known picture by John Tenniel, illustrator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), depicting Alice gazing up at the grinning Cheshire Cat perched on a branch of a tree. I felt very much like Alice while reading Vera Tobin’s book, as if I had fallen into a world in which the rules, concepts, and vocabulary were completely alien to my ow ... (read more)

I have always believed that, at a personal level, anything is possible, that if I desire to be a particular someone or do a particular something, I can. All my desires have been realistic: no hankerings for time travel or reinvention as a theoretical physicist, although both have enormous appeal. My desires have been possibilities: working as a volunteer in Africa, joining a choir, mountaineering, ... (read more)

The Merchant of Venice is a troublesome play. I have seen productions that have played up the comic aspects to an absurd and irritating degree while confining Shylock to the stereotype that bears his name. Some interpretations exploit the play as anti-Semitic propaganda. And none of the productions I have seen have united the two main narrative threads to any satisfying degree. Not surprisingly, T ... (read more)

The opening scene is a stunner. David Irving (Timothy Spall), top of the pile of Holocaust deniers, is giving a lecture. He is framed by darkness, we do not see the audience. ‘I say to you quite tastelessly,’ he says, ‘that more women died on the back seat of Senator Edward Kennedy’s car at Chappaquiddick than ever died in a gas chamber at Auschwitz.’ Irving speaks earnestly and with aut ... (read more)

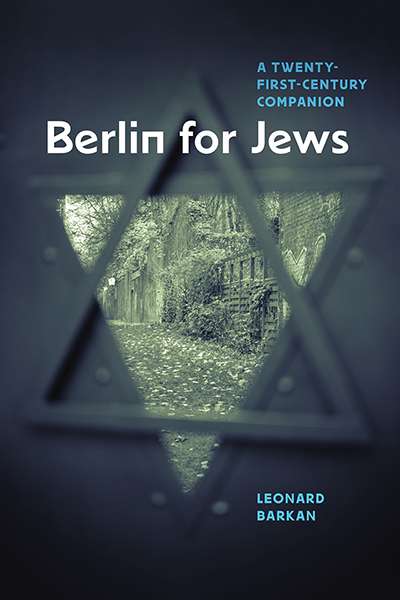

The title of this book has a resonance that would not occur, for example, in a text called ‘Paris for Jews’. Most readers will approach the work with understandings and expectations shaped by Hitler and the Holocaust. The title suggests that Berlin is a different city for Jews than for other visitors, and that Jewish Berlin itself is different from ecumenical Berlin. Is this book a travel guid ... (read more)