- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Natural History

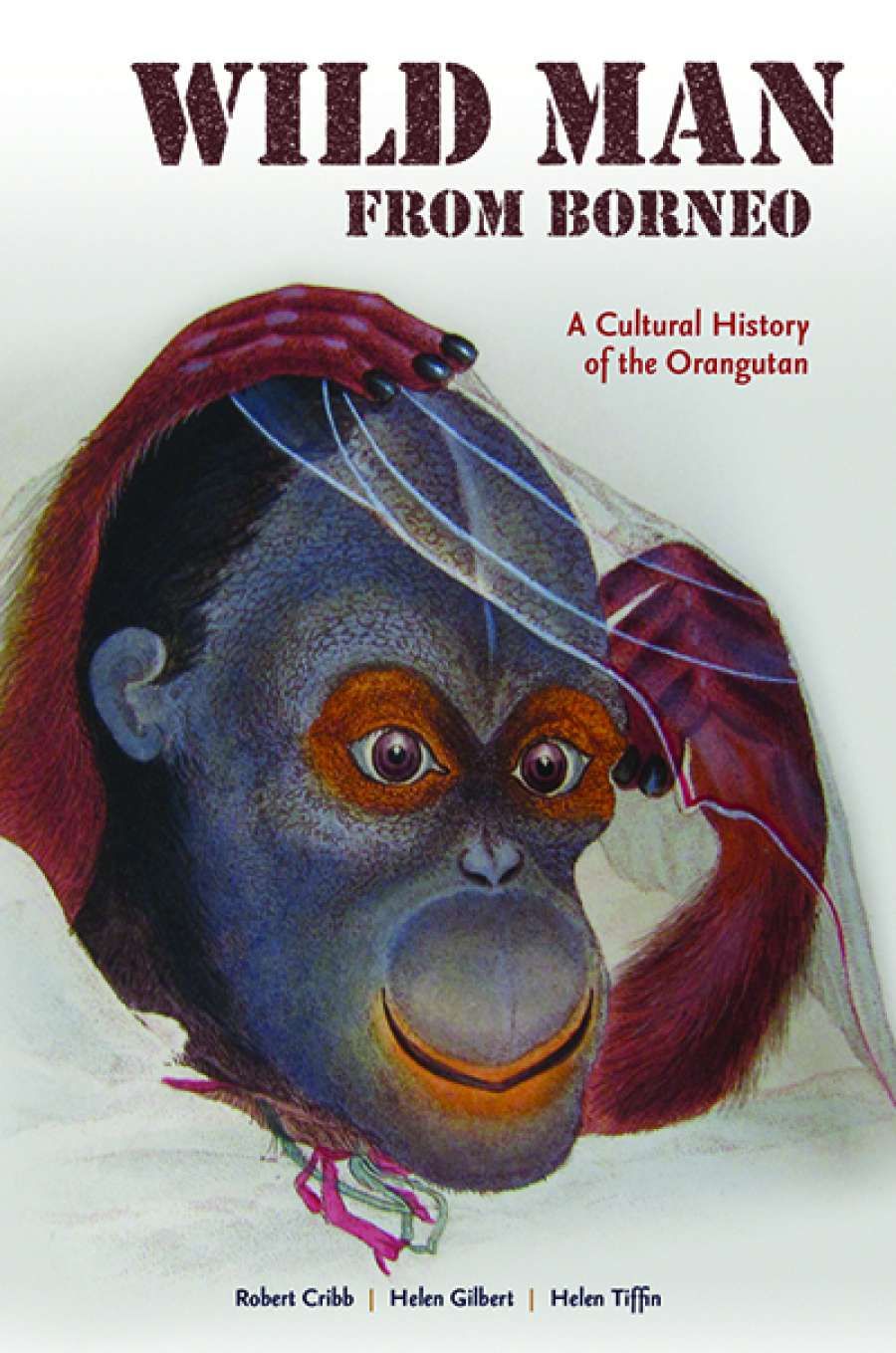

- Custom Article Title: Danielle Clode reviews 'Wild Man From Borneo: A cultural history of the Orangutan' by Robert Cribb, Helen Gilbert, and Helen Tiffen

- Book 1 Title: Wild Man From Borneo

- Book 1 Subtitle: A cultural history of the Orangutan

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Hawai‘i Press, US$28 pb, 330 pp, 9780824872830

The arrival of living orangutans in Europe, and the dissection of dead ones, cleared up some disagreements and generated many more. As a cultural history, this book is not as concerned with the nature of these great apes, as with our shifting perceptions of them. As the authors state: ‘this book is less about their actual behaviors (in the wild or in captivity) or their anatomy, tool use, intelligence, mating and rearing practices than it is about the orangutan–human encounter over four centuries, about the ways in which their actual or imagined presence has impinged upon us, and how we have envisioned, studied, and treated them.’

The role that the great apes played within debates over human rights and slavery make particularly compelling reading. Did the great apes have two hands or four feet? Could they speak, be ‘humanised’ or assimilated into society? Biologists, looking across the full diversity of living forms, were inclined to note surprising similarities, while others saw immeasurable differences. Just as they were enlisted in the evolutionary debates of the times, orangutans and the other apes were also recruited to the cause of racial discrimination.

‘Rewriting orangutans as humans helped enable the racial ranking of all other humans.’ In order to justify the superior position of white Caucasians, apparently inferior or more primitive races had to be demonstrated. A small number of little-known, physically distinctive populations with a long and independent history, like Australian Aborigines, were rather arbitrarily positioned at the bottom of the ladder to justify placing other races on intermediate rungs. Placing great apes, like orangutans, further down this scale, strengthened the illusion of a linear relationship between traits that actually exhibit fairly random and meaningless variation.

One of the most appealing elements of such ‘cultural’, as distinct from traditional, histories is their willingness to draw on rich but often neglected fictional resources to gain an understanding of how we view, and have viewed, the world. The early literary depictions of orangutans reflected our simultaneous fascination with, and fear of, the nearly human in the disturbing jailer/murderer ape characters of Walter Scott and Edgar Allan Poe. More recently, the orangutan seems positioned as wise narrator/guide or eco-warrior, perhaps most popularly exemplified by Terry Pratchett’s Librarian.

The use of orangutan actors in film is more complex, perhaps sharing more in common with circus performances and old-fashioned zoo displays than the more nuanced and complex representations found in literature. The chapter ‘Orangutans on Stage and Screen’ explores this difficult terrain, revealing a shift in focus away from what it means to be human towards how humans treat, or mistreat, other animals.

A Sumatran orangutan at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden

A Sumatran orangutan at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden

(photograph by Kabir Bakie via Wikimedia Commons)

I was disappointed that the detailed exploration of the cultural aspects of our scientific understanding of the orangutans did not continue into the twentieth century. Little is made of the way the study of animal behaviour served to embed and reinforce sexist clichés until it came under the critical eye of a more balanced feminist analysis. The switch from studies of male competition to female choice, or ‘promiscuity’ to polygamy, has as much cultural significance today as human–ape relations to slavery and human rights did in the past. Gender might have also added an interesting dimension to the individual relationships with orangutans (mostly young females), as well as their depictions in film and literature. The significance of women in pioneering work on the great apes and primates more broadly seems to have been skimmed over, while much of the discussion of modern conservation efforts (particularly given the orangutan’s role as charismatic megafauna in logging and palm oil debates) feels rather cursory.

That said, the great strength of this book lies in its historical analysis and it provides a detailed, insightful, and entertaining exploration of our ever-shifting relationship with our close cousins.

Comments powered by CComment