Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

The Leap by Paul Daley

Who should we celebrate, or perhaps fault, for the publishing success of books labelled ‘outback noir’ in Australia over the past decade? Our starting point could be Jane Harper’s bestselling book The Dry (2016). The cornerstone of the genre for the author of The Leap, Paul Daley, is the seminal Kenneth Cook novel, Wake in Fright, first published in 1961. The longevity of the novel owes much to the 1971 feature film of the same name, directed by Ted Kotcheff, remembered for the infamous filming of a visceral Kangaroo shoot and the actor Donald Pleasence playing a most unpleasant lech. The Wolf Creek film franchise also deserves an honourable mention, along with its larrikin psychopathic killer, Mick Taylor, if not the real-life mass murderer, Ivan Milat himself.

Walking Sydney: Fifteen walks with a city’s writers by Belinda Castles

During the walk she takes with Michelle de Kretser along the Cooks River, the bit that snakes between Hurlstone Park and Tempe, Belinda Castles, the author of Walking Sydney, muses on the impact of Sydney’s geography. ‘On the footpath-climb to skirt the golf course,’ she writes, ‘the village-like nature of Sydney makes itself felt, the way suburbs are enclosed and cut off by ridges and valleys, cliffs and rivers, the tentacles of the harbour. A city’s form has an effect on thinking and ways of being.’

Science Under Siege: How to fight the five most powerful forces that threaten our world by Michael Mann and Peter Hotez

Two distinguished professors have joined forces to write an impassioned book about the recent, concerted attacks on science. While they both live and work in the United States, where what they describe as the ‘forces of darkness’ are most active and influential, the problem they describe is truly global. Mann is a celebrated climate scientist who has been a leading voice in the field since the 1980s, while Hotez is a virologist who became involved in the public debate about the Covid-19 pandemic. The central argument of the book is that we face existential crises in both human health and the health of our planet. While the best hope of successfully tackling these challenges relies on science, there is now ‘politically and ideologically motivated opposition to science’, threatening both our ability to advance understanding of these complex issues and, equally important, the freedom of scientists to communicate their understanding.

1945: The Reckoning: War, empire and the struggle for a new world by Phil Craig

A wise scholar once advised me against using absolutes in historical writing. The first reason is functional. When you resort to words such as ‘everyone’, ‘everything’, and ‘nobody’, you invite trouble; most of the time you can find an exception. The second reason is more important. The use of such words can betray an approach that packages the messy past too neatly, where there is little room for nuance and even less for uncertainty. Confidence doesn’t necessarily produce the best results.

Electric Spark: The enigma of Muriel Spark by Frances Wilson

Some literary biographies are best known for their gestation – or malgestation. Some authors, we might go further, should have a big sign around their neck – noli me tangere. Muriel Spark is one of them. Her voluminous archive, lovingly tended all her life, is full of booby traps. Twice she went into battle with biographers: first Derek Stanford, a former lover; then Martin Stannard, whose biography of Evelyn Waugh she had admired.

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

‘AI will kill us/save us: Hype and harm in the new economic order’

Ilya Sutskever was feeling agitated. As Chief Scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the AI models used in ChatGPT and in Microsoft’s products, he was a passionate advocate for the company’s mission of achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) before anybody else. OpenAI defines AGI as ‘highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work’, the development of which will benefit ‘all of humanity’. OpenAI’s mission, Sutskever believed, gave humanity its best chance of getting to AGI safely. But he worried about failing the mission. He fretted to his colleagues: What if bad actors came after its technology? What if they cut off his hand and slapped it on a palm scanner to access its secrets?

‘Archives and Hives: Three books which tell of Sylvia Plath’s spring’

For seven years after her 1963 burial, Sylvia Plath lay in an unmarked grave near St Thomas the Apostle Church in Heptonstall, West Yorkshire. The gravestone, when it came, bore her birth and married names, Sylvia Plath Hughes, the years of her birth and death, and a line from Wu Cheng-en’s sixteenth-century novel Monkey King:Journey to the West: ‘Even amidst fierce flames, the golden lotus can be planted.’

A Life in Letters by Robert Chevanier and André A. Devaux, translated from French by Nicholas Elliott

In his otherwise bleak 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carré lets himself have a little fun with the character of Elizabeth Gold. She is an idealistic Jewish woman in her mid-twenties who works in a small library in the London neighbourhood of Bayswater. She is also a member of the British Communist Party. For Liz, however, membership is less a matter of ideology than a token of her moral commitment to peace work and the alleviation of poverty. She is disdainful of her local branch, with its petty ambitions to be ‘a decent little club, nice and revolutionary and no fuss’ – unlike her comrades in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), whose determined struggle against the militarism and decadence of the capitalist West she admires from afar.

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

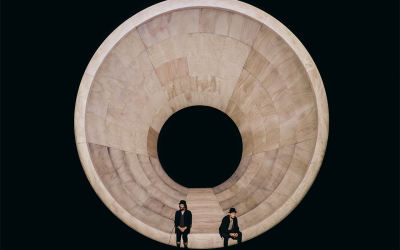

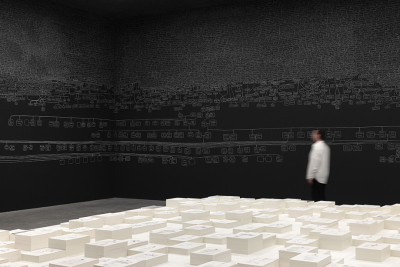

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.