Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

The Odyssey by Homer, translated from ancient Greek by Daniel Mendelsohn

After the horror of war, the difficulty of return – angry seas, lost comrades, plotters at home. Daniel Mendelsohn teaches at Bard College and writes for The New York Review of Books. His compelling new translation of the Odyssey acknowledges the themes of this story have been repeated over millennia: separation, trials, and reunion.

Ripeness by Sarah Moss

Sarah Moss’s tenth novel, Ripeness, charts the burden of bearing witness to tragedies, both personal and historical. At the heart of the story are two sisters from rural Ireland: Lydia, a ballerina, and Edith, a school-leaver due to commence a degree at Oxford. When Lydia falls pregnant, the girls’s mother charges Edith with the responsibility of assisting in the birth and overseeing the transfer of the baby into the care of his adoptive mother.

Science Under Siege: How to fight the five most powerful forces that threaten our world by Michael Mann and Peter Hotez

Two distinguished professors have joined forces to write an impassioned book about the recent, concerted attacks on science. While they both live and work in the United States, where what they describe as the ‘forces of darkness’ are most active and influential, the problem they describe is truly global. Mann is a celebrated climate scientist who has been a leading voice in the field since the 1980s, while Hotez is a virologist who became involved in the public debate about the Covid-19 pandemic. The central argument of the book is that we face existential crises in both human health and the health of our planet. While the best hope of successfully tackling these challenges relies on science, there is now ‘politically and ideologically motivated opposition to science’, threatening both our ability to advance understanding of these complex issues and, equally important, the freedom of scientists to communicate their understanding.

The Sea in the Metro by Jayne Tuttle

Jayne Tuttle’s The Sea in the Metro is the third book in a trilogy of memoirs about living, working, and becoming a mother in Paris. Like Paris or Die (2019) and My Sweet Guillotine (2022), Tuttle’s latest book applies a sharp scalpel to her own psyche while playing with genre. She explores the brutal realities of giving birth and raising a toddler in a foreign city, the seemingly impossible task of balancing motherhood with paid work, the joys and hardships of striving to be a capital ‘W’ writer while copywriting for cash, and what family might look like in brittle, Parisian culture. Tuttle also examines the complex ramifications of a near-death experience and a hospital birthing trauma on her ongoing physical and mental health – and intimate relationships.

Prove It: A scientific guide for the post-truth era by Elizabeth Finkel

Living alongside the world’s only native black swans, Australians should be more alive to the provisional nature of truth than most. For thousands of years of European history, the ‘fact’ that ‘all swans are white’ was backed up with an overwhelming data set that only the delusional – or a philosopher – would debate. But as Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume pointed out, the difficulty with inductive reasoning is that it can seem incontrovertible all the way up until it is not. But if the truth is always shifting, where do we find solid ground when our lives depend on it? And to what absolutes and experts can we refer in an era of wilful misinformation, institutional mistrust, and anti-expert populism?

‘AI will kill us/save us: Hype and harm in the new economic order’

Ilya Sutskever was feeling agitated. As Chief Scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the AI models used in ChatGPT and in Microsoft’s products, he was a passionate advocate for the company’s mission of achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) before anybody else. OpenAI defines AGI as ‘highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work’, the development of which will benefit ‘all of humanity’. OpenAI’s mission, Sutskever believed, gave humanity its best chance of getting to AGI safely. But he worried about failing the mission. He fretted to his colleagues: What if bad actors came after its technology? What if they cut off his hand and slapped it on a palm scanner to access its secrets?

Pissants by Brandon Jack

In The Season, Helen Garner describes a photograph of Australian Football League player Charlie Curnow celebrating a goal: ‘It’s Homeric: all the ugly brutality of a raging Achilles, but also this strange and splendid beauty.’ There is a mythic image in Australian culture of the AFL player doing battle on the football oval with the strength of Hercules or the wit of Odysseus. Brandon Jack’s Pissants, his first novel, is an inversion of this mythopoeia; it is an exposé of football culture, the false pluralism of Australian masculinity, and a deranged form of identity that runs through ‘the club’. It shows the average life of a footballer at the fringes of a team list. Jack, having played for the AFL’s Sydney Swans from 2013 to 2017, has firsthand experience of the (in)famous ‘Bloods Culture’ – one built on a mantra of self-sacrifice, discipline, and unity – and this experience shows throughout the novel.

Electric Spark: The enigma of Muriel Spark by Frances Wilson

Some literary biographies are best known for their gestation – or malgestation. Some authors, we might go further, should have a big sign around their neck – noli me tangere. Muriel Spark is one of them. Her voluminous archive, lovingly tended all her life, is full of booby traps. Twice she went into battle with biographers: first Derek Stanford, a former lover; then Martin Stannard, whose biography of Evelyn Waugh she had admired.

Yilkari: A desert suite by Nicolas Rothwell and Alison Nampitjinpa Anderson

Outsiders, mostly white men seeking answers to burning existential questions, have long been ineluctably drawn to Australian deserts. The continental interior, with its deep-time mysteries, has lured not only explorers on fatal quests, but also lone anthropologists, philosophers, and other restless wanderers in search of themselves, burdened with their interrogations and yearnings for higher truth.

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

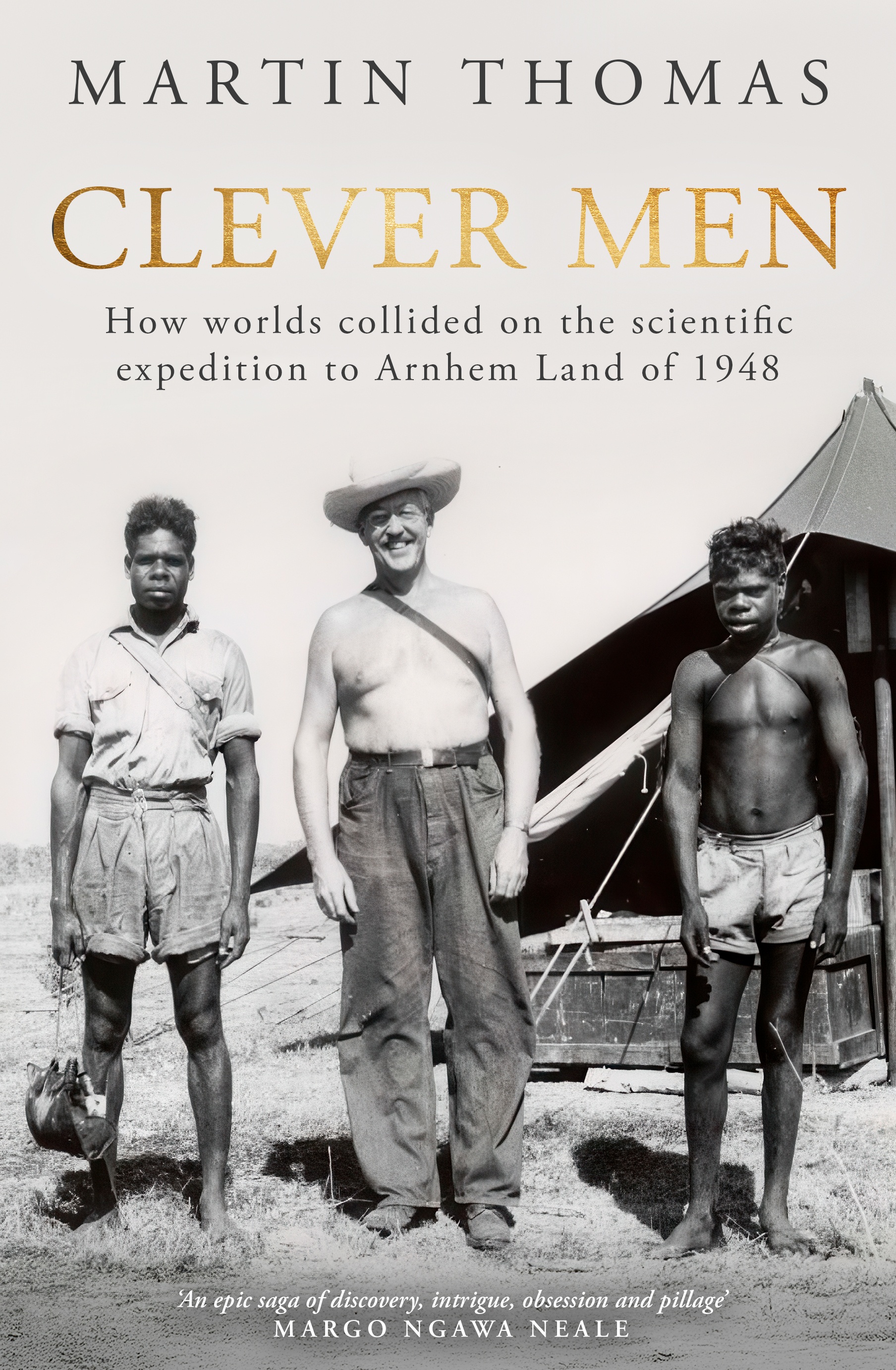

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.