Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

1945: The Reckoning: War, empire and the struggle for a new world by Phil Craig

A wise scholar once advised me against using absolutes in historical writing. The first reason is functional. When you resort to words such as ‘everyone’, ‘everything’, and ‘nobody’, you invite trouble; most of the time you can find an exception. The second reason is more important. The use of such words can betray an approach that packages the messy past too neatly, where there is little room for nuance and even less for uncertainty. Confidence doesn’t necessarily produce the best results.

‘Land rights interrupted?: How Whitlam’s dismissal changed the history of First Nations land repossession’

On the steps of Federal Parliament, a scrum assembled. Reporters jostled for position, enraged members of the public shouted over one another, advisers stood with faces drained of composure – even a comedian was caught in the fray. At the centre stood the tall and imposing figure of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, listening as the governor-general’s official secretary read the proclamation dissolving Parliament. The moment, instantly mythic, would be remembered as ‘the dismissal’ – the most audacious constitutional rupture in Australian history, one that continues to haunt democratic life half a century on.

Letters – October 2025

My career began at Australian Book Review, and as such I’ve been prompted to reflect on the importance of publications such as ABR to ensuring a robust critical culture in Australia in the wake of Meanjin’s closure. The decision was announced on September 4 that Meanjin, one of Australia’s longest-running literary journals, would cease to be published by its custodian, Melbourne University Publishing, and that the editor and I would be made redundant.

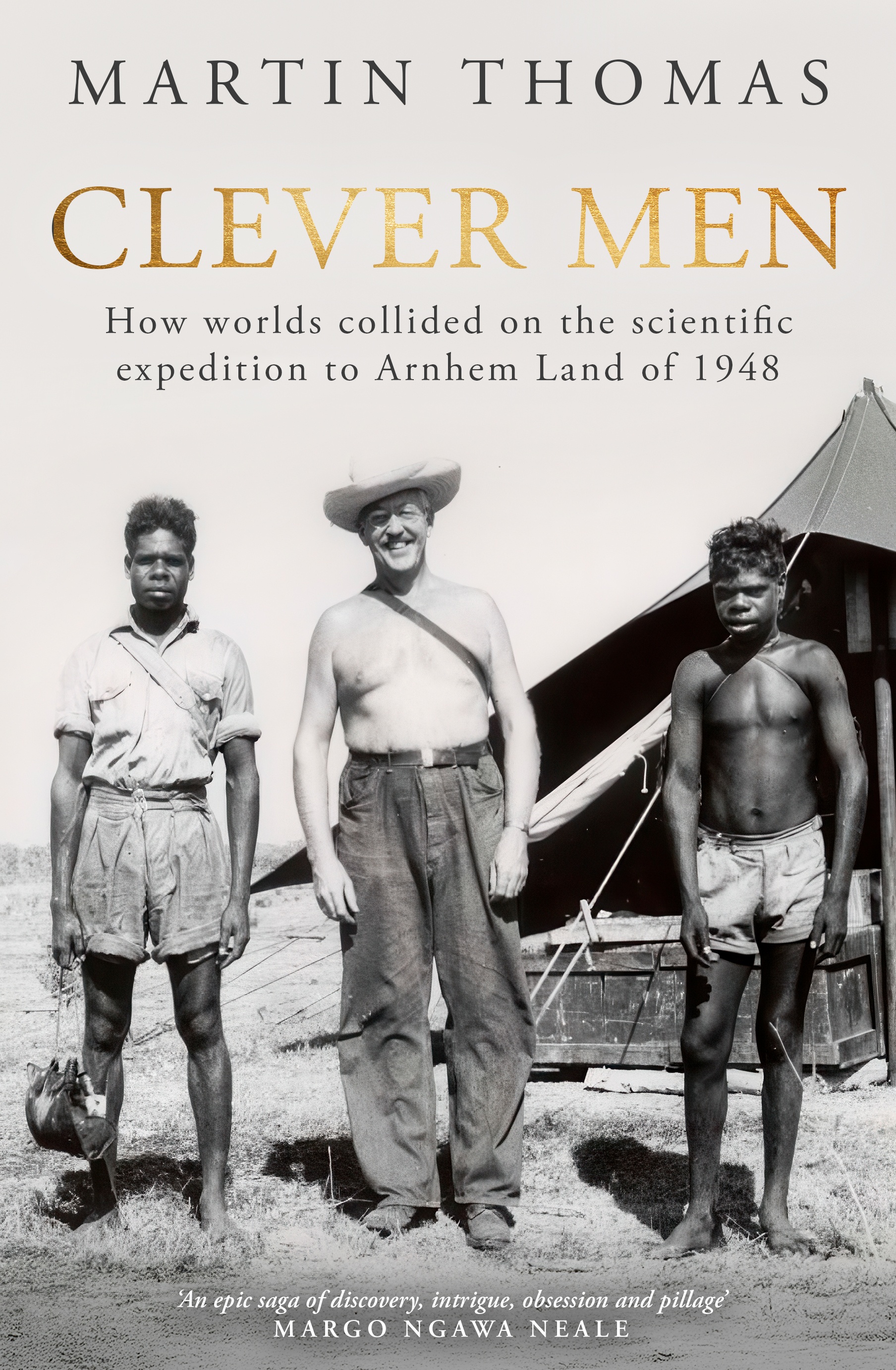

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

Now, the People!: Revolution in the twenty-first century by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, translated from French by David Broder

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is famous in France for his booming eloquence, his rich vocabulary, and his deep knowledge of history and politics. The firebrand orator was born in 1951 in Tangier, Morocco, to parents of Spanish and Sicilian descent, then moved to France with his mother in 1962. After a degree in philosophy and languages he was a schoolteacher before becoming a political organiser and elected politician, notably from inner-city Marseille.

‘AI will kill us/save us: Hype and harm in the new economic order’

Ilya Sutskever was feeling agitated. As Chief Scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the AI models used in ChatGPT and in Microsoft’s products, he was a passionate advocate for the company’s mission of achieving Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) before anybody else. OpenAI defines AGI as ‘highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work’, the development of which will benefit ‘all of humanity’. OpenAI’s mission, Sutskever believed, gave humanity its best chance of getting to AGI safely. But he worried about failing the mission. He fretted to his colleagues: What if bad actors came after its technology? What if they cut off his hand and slapped it on a palm scanner to access its secrets?

Our Familiars: The meaning of animals in our lives by Anne Coombs

The unbelievable lacework of it all – the patterns and linkages, the flickerings of knowledge and mystery, the astonishing shapes – is what Anne Coombs’s Our Familiars: The meaning of animals in our lives explores. This is a family book; specifically, a multi-species family book. Intimacies made between bodies is the soil in which the work is grown. And it comes from a writer who spent a lifetime thinking about, writing for, and working towards companionship, co-operation, and the safety of others. It is a posthumous publication too; a work fed and raised by Coombs, but finished, edited, and carried into the world by Susan Varga, Anne’s partner of thirty-three years, and close friend Joyce Morgan. Coombs died in December 2021, not long after the Black Summer fires and the Covid-19 pandemic – a time when all our interdependencies were raging (as they continue to).

‘Questions for Mai: Joshua Reynolds’s portrait and the memory of Empire’

Zoom in. The most unusual detail in this painting is the left hand, with tattooed dots carefully spaced across its back and knuckles. The fingers themselves are poorly done. The thumb and pointer are folded into the figure’s thick cloth folds, but the other three digits lie on the material like tapered slugs. Today they might be held up as evidence of AI image generation – bad hands are the quickest tell. In the eighteenth century, to the initiated, bad hands were a sign that the work came from the studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Fierceland by Omar Musa

Omar Musa’s first novel, Here Come the Dogs (2014), is a rousing dramatisation of the combustible sense of displacement and dissatisfaction simmering at the underrepresented margins of Australian life. Its protagonists are singular and compelling: each is tender and violent, hopeful and despairing, pitiful and triumphant. They all possess a uniquely hybrid identity, and each is searching for something that is always out of reach.

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

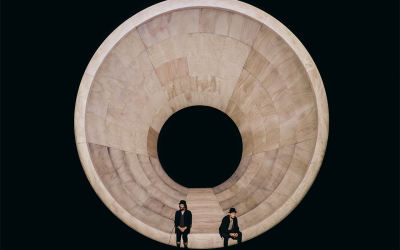

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.