Albanese’s ‘Australian Way’

Current Issue

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

- Events

- Book reviews

- Arts criticism

- Prizes & Fellowships

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

Poet of the Month with Ellen van Neerven

Ellen van Neerven is a writer and editor of Mununjali and Dutch heritage. Their books include Heat and Light (2014), Comfort Food (2016), Throat (2020), and Personal Score (2023). Ellen’s first book, Heat and Light, was the recipient of the David Unaipon Award, the Dobbie Literary Award, and the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Indigenous Writers’ Prize. Ellen’s second book, Comfort Food, was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Kenneth Slessor Prize and highly commended in the 2016 Wesley Michel Wright Prize. They live and write on unceded Yagera and Turrbal dhagun.

1945: The Reckoning: War, empire and the struggle for a new world by Phil Craig

A wise scholar once advised me against using absolutes in historical writing. The first reason is functional. When you resort to words such as ‘everyone’, ‘everything’, and ‘nobody’, you invite trouble; most of the time you can find an exception. The second reason is more important. The use of such words can betray an approach that packages the messy past too neatly, where there is little room for nuance and even less for uncertainty. Confidence doesn’t necessarily produce the best results.

The Odyssey by Homer, translated from ancient Greek by Daniel Mendelsohn

After the horror of war, the difficulty of return – angry seas, lost comrades, plotters at home. Daniel Mendelsohn teaches at Bard College and writes for The New York Review of Books. His compelling new translation of the Odyssey acknowledges the themes of this story have been repeated over millennia: separation, trials, and reunion.

Prove It: A scientific guide for the post-truth era by Elizabeth Finkel

Living alongside the world’s only native black swans, Australians should be more alive to the provisional nature of truth than most. For thousands of years of European history, the ‘fact’ that ‘all swans are white’ was backed up with an overwhelming data set that only the delusional – or a philosopher – would debate. But as Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume pointed out, the difficulty with inductive reasoning is that it can seem incontrovertible all the way up until it is not. But if the truth is always shifting, where do we find solid ground when our lives depend on it? And to what absolutes and experts can we refer in an era of wilful misinformation, institutional mistrust, and anti-expert populism?

A Life in Letters by Robert Chevanier and André A. Devaux, translated from French by Nicholas Elliott

In his otherwise bleak 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carré lets himself have a little fun with the character of Elizabeth Gold. She is an idealistic Jewish woman in her mid-twenties who works in a small library in the London neighbourhood of Bayswater. She is also a member of the British Communist Party. For Liz, however, membership is less a matter of ideology than a token of her moral commitment to peace work and the alleviation of poverty. She is disdainful of her local branch, with its petty ambitions to be ‘a decent little club, nice and revolutionary and no fuss’ – unlike her comrades in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), whose determined struggle against the militarism and decadence of the capitalist West she admires from afar.

Now, the People!: Revolution in the twenty-first century by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, translated from French by David Broder

Jean-Luc Mélenchon is famous in France for his booming eloquence, his rich vocabulary, and his deep knowledge of history and politics. The firebrand orator was born in 1951 in Tangier, Morocco, to parents of Spanish and Sicilian descent, then moved to France with his mother in 1962. After a degree in philosophy and languages he was a schoolteacher before becoming a political organiser and elected politician, notably from inner-city Marseille.

‘Weather’

These days, evenings are heavy

with clouds that refuse to crack, to open

a window is let in the night

creatures, which flutter and tumble

into the glow of a phone

What Is Wrong with Men by Jessa Crispin & The Male Complaint by Simon James Copland

Although the tone of their commentaries differs, Jessa Crispin’s What Is Wrong with Men and Simon James Copland’s The Male Complaint are, more or less, examining the same thing: the workings of the patriarchy in general and what specifically has gone wrong, especially in recent times, with what Crispin refers to as ‘the tug of war’ between men and women.

Ripeness by Sarah Moss

Sarah Moss’s tenth novel, Ripeness, charts the burden of bearing witness to tragedies, both personal and historical. At the heart of the story are two sisters from rural Ireland: Lydia, a ballerina, and Edith, a school-leaver due to commence a degree at Oxford. When Lydia falls pregnant, the girls’s mother charges Edith with the responsibility of assisting in the birth and overseeing the transfer of the baby into the care of his adoptive mother.

ABR Arts

Bruckner and Strauss: A thoughtful performance of works by two Romantic masters

Letter from Santa Fe: 'Marriage of Figaro' and Wagner’s 'Die Walküre' at the Opera House

‘Waiting for Godot: Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter reunite for Beckett’s classic’

Book of the Week

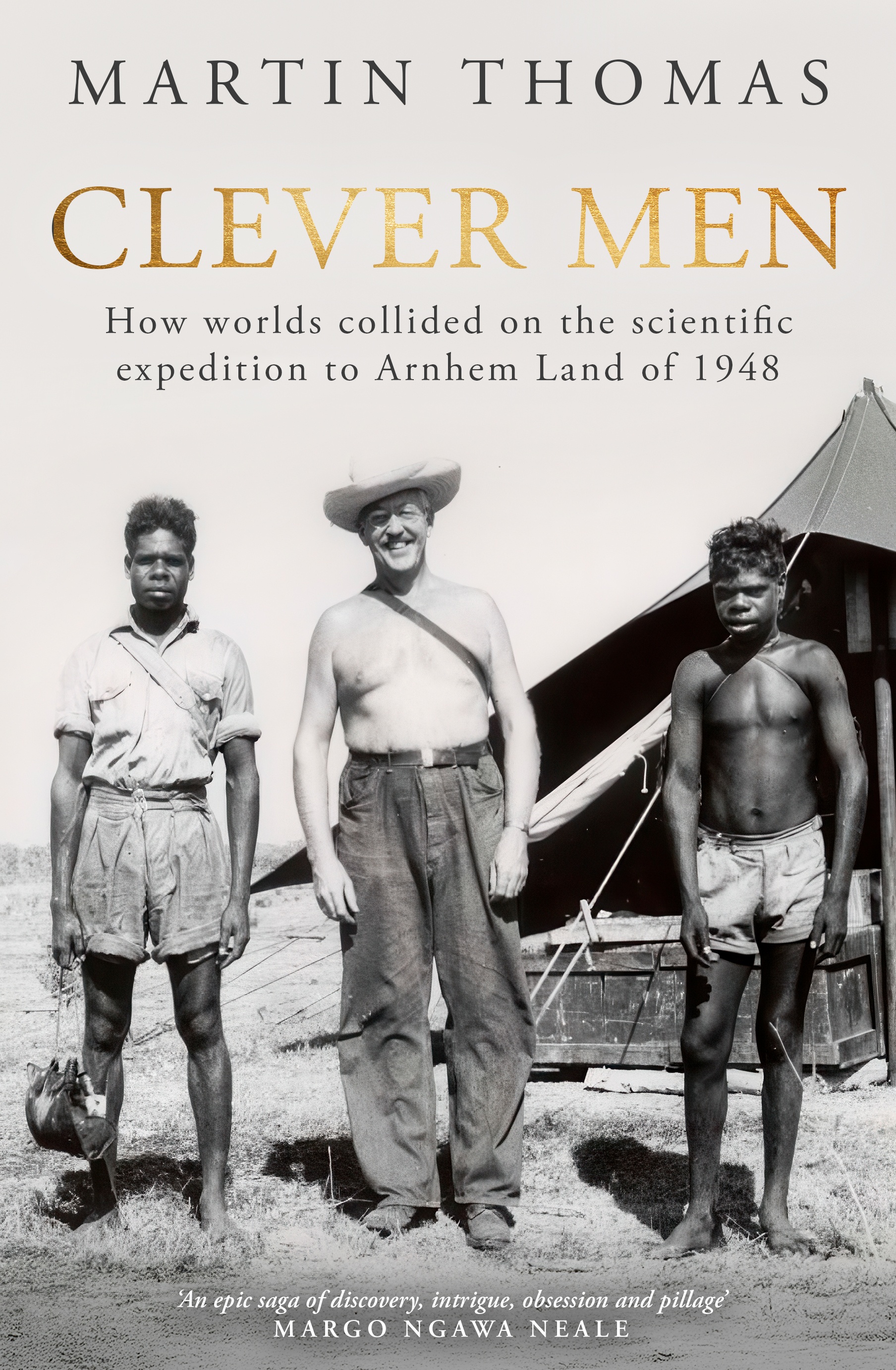

Clever Men: How worlds collided on the scientific expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948 by Martin Thomas

Soon after the conclusion of the 1948 Arnhem Land expedition, its leader, Charles Pearcy Mountford, an ethnologist and filmmaker, was celebrated by the National Geographic Society, a key sponsor of the expedition, along with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC and the Commonwealth Department of Information. In presenting Mountford with the Franklin L. Burr Prize and praising his ‘outstanding leadership’, the Society effectively honoured his success in presenting himself as the leader of a team of scientists working together in pursuit of new frontiers of knowledge. But this presentation is best read as theatre. The expedition’s scientific achievements were middling at best and, behind the scenes, the turmoil and disagreement that had characterised the expedition continued to rage.

From the Archive

Sense and Nonsense in Australian History by John Hirst

John Hirst is a throwback. I don’t mean in his political views, but in his sense of his duty as an historian. He belongs to a tradition which, in this country, goes back to the 1870s and 1880s, when the Australian colonies began to feel the influence of German ideas about the right relationship between the humanities and the state. Today it is a tradition increasingly hard to maintain. Under this rubric, both historians and public servants are meant to offer critical and constructive argument about present events and the destiny of the nation. Henry Parkes was an historian of sorts, and he was happy to spend government money on the underpinnings of historical scholarship in Australia. The Historical Records of New South Wales was one obvious result, and that effort, in itself, involved close cooperation between bureaucrats and scholars. Alfred Deakin was likewise a man of considerable scholarship (and more sophisticated than Parkes), whose reading shaped his ideas about national destiny, and who nourished a similar outlook at the bureaucratic level.