- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Festivals

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The 23rd Biennale of Sydney: rīvus

- Article Subtitle: An exemplary puzzle

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The twenty-third Biennale has been highly anticipated through two long years since Brook Andrew’s twenty-second Biennale suddenly closed in March 2020 as Covid took hold of the country, not to reopen for three months.

This year’s guiding idea, rīvus – meaning stream, but embracing rivers, fresh water, saltwater, lagoons, banks, confluences – is peculiarly topical, as water resources, in both scarcity and flood, become every year a more urgent issue.

Commissioned videos at each venue show river custodians from around the globe emphasising the common difficulties uniting different campaigns, and are a key to the collectivist ethics of this Biennale. Living in Sydney for two years to develop rīvus, Roca worked with a local curatorium – Paschal Daantos Berry, Anna Davis, Hannah Donnelly, and Talia Linz – that has done splendidly. Local knowledge shines at every venue in astute juxtapositions of works and spacious presentations: Covid social distancing has affected exhibition design positively. This year, venues are geographically concentrated, walkable: the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), National Art School (NAS), (in partnership with Artspace), Pier 2/3 at Walsh Bay, The Cutaway at Barangaroo, and Stargazer Lawn above it, looking over the Harbour; ACE at Parramatta, the only venue I have not yet visited, is the exception, with a small selection.

With rīvus many river sites and narratives are explored in what Roca called ‘more a delta than a river’: from the magnificent possum-skin cloak project led by Carol McGregor to commemorate the 180th anniversary of the notorious Myall Creek massacre seen at the National Art School’s convict-built sandstone building, to Barkandji elder Badger Bates and John Kelly and Rena Shein’s astonishing interventions at AGNSW, including the canoe-making project claiming its cultural place among the European paintings. (The Baaka River is a listed participant in the Biennale.)

John Kelly & Rena Shein, Nyanghan Nyinda Me You, 2016-ongoing. Courtesy the artists. Co-created with Dalaigur Preschool & Family Services Community, Booroongen Djugun Community, Greenhill Public School, Catherine Keyzer & Julia Sideris of we3. Background: Badger Bates, Barka The Forgotten River and the desecration of the Menindee Lakes, 2021-2022 (detail). Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts. Courtesy the artist. Foreground: Rex Greeno, Tasmanian Aboriginal paperbark canoe, 2012 (detail). Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney (2022) was made possible with generous assistance from Arts Tasmania by the Minister for the Arts. On loan from the National Museum of Australia. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Art Gallery of New South Wales. (Photograph by Document Photography)

John Kelly & Rena Shein, Nyanghan Nyinda Me You, 2016-ongoing. Courtesy the artists. Co-created with Dalaigur Preschool & Family Services Community, Booroongen Djugun Community, Greenhill Public School, Catherine Keyzer & Julia Sideris of we3. Background: Badger Bates, Barka The Forgotten River and the desecration of the Menindee Lakes, 2021-2022 (detail). Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts. Courtesy the artist. Foreground: Rex Greeno, Tasmanian Aboriginal paperbark canoe, 2012 (detail). Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney (2022) was made possible with generous assistance from Arts Tasmania by the Minister for the Arts. On loan from the National Museum of Australia. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Art Gallery of New South Wales. (Photograph by Document Photography)

I applaud this activism. I find the innovative ways artists are working collectively, with and against institutions, fascinating. So why am I less than enthusiastic about rīvus? The Latin word ‘rivus’ also invokes rivalry, and Roca said he found the project ‘grittier’ than anticipated, but in truth this grittiness is less evident, and that is part of the problem. If anything, rīvus is too consistent in gathering together water-themed works in a literal way. It is an odd mix of the illustrative and the exhortatory. In (correctly) insisting on the precariousness of the rivers and locations that participants address, there is a prevailing tone of poetic regret, of consensual reverence. Exploring ‘chthonic forces’ is fine and good – David Haines and Joyce Hinterding at The Cutaway are the best in this mode, with a glorious immersive soundscape accompanying their videoed creek. Look there, too, for Zheng Bo’s delicious videos, the funniest, most erotic, and perhaps the most perfectly elegiac works in an overcrowded field. But where is the rage? It’s almost as if the curators have not trusted the amplitude of their own metaphor. And this makes for too much art that is, in the end, too descriptive, and sometimes just too easy.

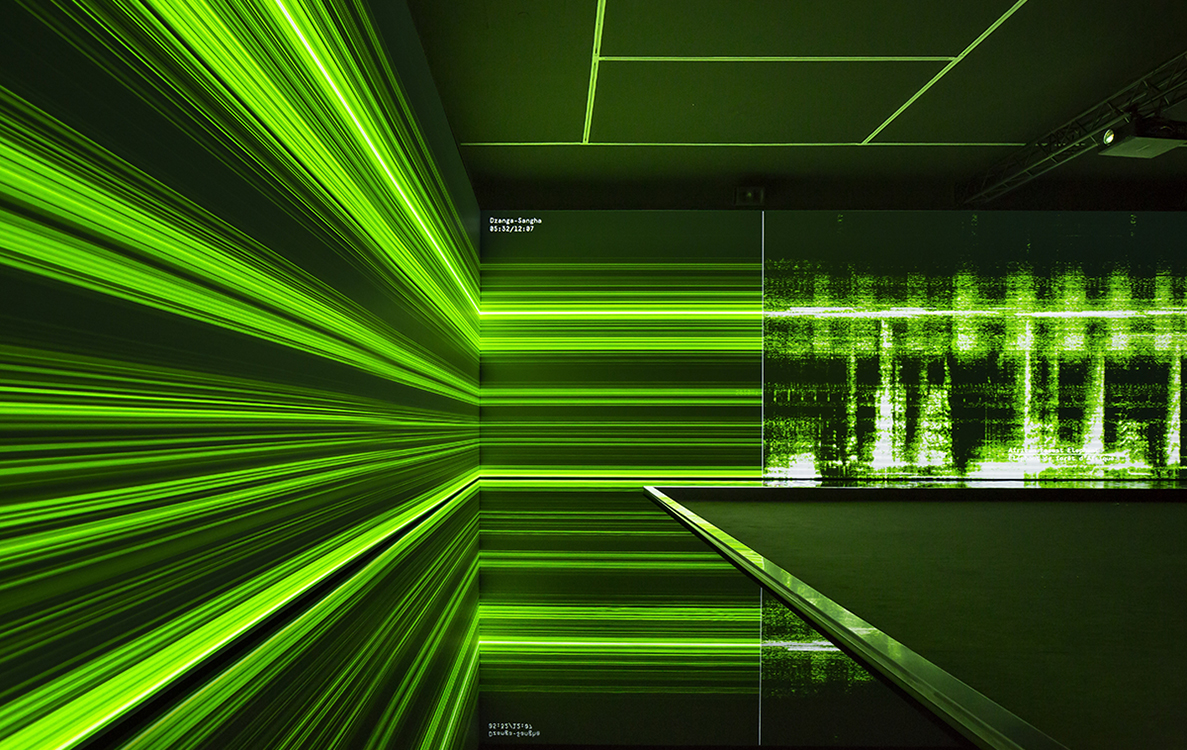

I do relish the stimulating difficulties in rīvus. Roca’s use of the term ‘participants’, rather than artists, honestly recognises the range of objects included, such as the extraordinary Devonian era Canowindra fish fossil displayed at the MCA on loan from the Australian Museum, and the project’s determined hybridity. Take The Great Animal Orchestra, this Biennale’s star exhibit, impeccably presented on the Barangaroo Stargazer Lawn in a purpose-built tent. A fabulous auditory science project with a grim record of species extinction, it is the most obviously documentary of many ‘participations’. But the Barnum & Bailey title of The Great Animal Orchestra also usefully recalls the late nineteenth century’s extraordinary range of ‘attractions’ in popular entertainment, including phrenologists, quick-sketch artists, escape acts, dancing, singing, and comedy, with cinema the most enduring innovation.

Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists, The Great Animal Orchestra, 2016. Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (acq. 2017). View of the exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016 (Photograph by Luc Boegly)

Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists, The Great Animal Orchestra, 2016. Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain (acq. 2017). View of the exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, 2016 (Photograph by Luc Boegly)

I think we are seeing another such hybrid moment with contemporary art exhibitions, with their opportunities for exactly this sort of cultural experiment. When I note inclusions that are clearly not ‘art’ – concrete Sydney Harbour seawall habitat units at Pier 2/3, for instance – here and in other recent exhibitions, I simultaneously rejoice in the elasticity of the temporary exhibition model – initiated in the nineteenth century with the great universal expositions – and puzzle about holding on to the singular metaphoric power of art. I like this experimental conversation across and between diverse ways of thinking, knowing, making; perhaps I will savour it more when the delineations between ‘participants’ are even more marked. What I do not celebrate is a certain dogged righteousness that mistakes articulating an issue (however important) with making art. This is where the lovely possum-skin cloak by Carol McGregor et al., rich in historical and present-day implications, or Jessie French’s beguiling algae monochrome drops, succeed; other ambitious works, however, such as Joey Holder’s immersive video installation (also at NAS), settle on one low gloomy note. Video and photography, in a quasi-documentary mode, are not always the best answer.

I like far better the Biennale’s array of modest drawings by various artists exploring local knowledges both scientific and affectionate: the sly wit of Inuit artist Qavavau Manumie, the fastidious accounts of Amazon flora by Abel Rodríguez (Mogaje Guihu) – both at the MCA) – and Pushpa Kumari’s wonderful personification of Mother Ganges at NAS, her huge drawing in, but also exceeding, the Madhubani tribal mode. It pictures the river from her origins in the Himalaya to populated cities close to its delta, and appears in the same room as stupendous linocuts by Torres Strait islander Teho Ropeyarn. A great strength of rīvus is works by Indigenous artists that bring long knowledge to questions of water/land custodianship, and act on that knowledge. One extraordinary gesture: at The Cutaway D Harding has marked a single line along a wall that speaks to (not yet for) a creek near Woorabinda in Central Queensland, the mission settlement where their grandmother was raised.

Speaking of The Cutaway, this venue proves that accessible locations encourage audience engagement. Nearly fifty years after the first Biennale of Sydney in 1973, the city has long since embraced the event, but still it was marvellous to see a Saturday throng of families and children at The Cutaway. They were not disappointed. French artist Tabita Rezaire’s spunky animations, intercut with speech and song, pulsing, are irresistible; so is her Mamelles Ancestrales at the MCA, accompanied by Kiki Smith’s exquisite jacquard tapestries. (Two maternal mythologies, totally different sources. Stunning.)

Background Left to Right: Kiki Smith, Harbor, 2015; Cathedral, 2013; Spinners, 2014; Congregation, 2014; and Underground, 2012. Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous support from Goethe-Institut Australia. Courtesy of the artist & Pace Gallery. Foreground: Tabita Rezaire, Mamelles Ancestrales, 2019. Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous assistance from the Embassy of France in Australia and L'Institut Français. Courtesy of the artist & Goodman Gallery. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. (Photography by Document Photography).

Background Left to Right: Kiki Smith, Harbor, 2015; Cathedral, 2013; Spinners, 2014; Congregation, 2014; and Underground, 2012. Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous support from Goethe-Institut Australia. Courtesy of the artist & Pace Gallery. Foreground: Tabita Rezaire, Mamelles Ancestrales, 2019. Presentation at the 23rd Biennale of Sydney was made possible with generous assistance from the Embassy of France in Australia and L'Institut Français. Courtesy of the artist & Goodman Gallery. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. (Photography by Document Photography).

Also at The Cutaway is the superlative siting of two brilliant works: Wiradjuri artist Nicole Foreshew’s YIRUNG BILA (SKY HEAVEN RIVER) is an enormous fall of earth-caked fabric against the towering sandstone cliff. The Biennale’s quintessential image of combined delicacy and grit, beauty and resistance, it is adjacent to He Toka Tū Moana | She’s a Rock by Mata Aho Collective, four Māori women. Using sturdy industrial strapping, and drawing on traditional Māori strapping systems called Kawe, this monumental intervention sites strength and resistance in the present moment.

Left to Right: Cave Urban, Flow, 2022 (detail). Courtesy the artists; Mata Aho Collective, He Toka Tū Moana: She's a Rock, 2022. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from Creative New Zealand. Courtesy the artists; Paula de Solminihac, Fogcatcher , 2018-2021. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous assistance from Graeme and Mabie Briggs and assistance from the Catholic University of Chile and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Government of Chile. Courtesy the artist; Nicole Foreshew, YIRUNG BILA (SKY HEAVEN RIVER), 2022. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, The Cutaway at Barangaroo. (Photograph by Document Photography)

Left to Right: Cave Urban, Flow, 2022 (detail). Courtesy the artists; Mata Aho Collective, He Toka Tū Moana: She's a Rock, 2022. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from Creative New Zealand. Courtesy the artists; Paula de Solminihac, Fogcatcher , 2018-2021. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous assistance from Graeme and Mabie Briggs and assistance from the Catholic University of Chile and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Government of Chile. Courtesy the artist; Nicole Foreshew, YIRUNG BILA (SKY HEAVEN RIVER), 2022. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts. Courtesy the artist. Installation view, 23rd Biennale of Sydney, rīvus, 2022, The Cutaway at Barangaroo. (Photograph by Document Photography)

At Walsh Bay’s Pier 2/3, used again for art exhibitions after ten years, rīvus sparkles in the Harbour water’s light with a particularly fine group of works. Australian Clare Milledge has ample room to work her idiosyncratic magic; Yuko Mohri’s delicate, whimsical water circulation sculpture, made from components sourced in Sydney, is in striking counterpoint with Yoan Capote’s great golden evocation of the forbidding seas that separate Cuba from her powerful northern neighbour; and American Duke Riley’s riff on Brooklyn’s waterside, with plastic scrimshaw and faux-naïve graphics, brings a welcome note of humour in an exhibition remarkably lacking in ratbaggery. By the end, I appreciated the respect and collectivity, but was longing for rebellion.

Accompanying the exhibition is a thick compendium that is more artist’s book than exhibition guide. It’s a lovely thing, a luxury collector’s item that is a tad baffling in the project’s context of activism and immediacy. In coming months, I’ll be looking instead to the Biennale’s website, for the week’s events and talks. Rīvus is intriguing and perplexing, but undeniably a rich challenge worth taking up.

The Biennale of Sydney continues until 13 June 2022. The catalogue is $79.95.

This article is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.