- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Peter Grimes

- Article Subtitle: A magnificent new production of Britten’s opera

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sadly, stage productions of Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s opera Peter Grimes are now few and far between in Australia, notwithstanding the fact that the work’s exploration of psychological distress and social ostracisation has lost none of its currency. Britten’s score, while incorporating significant modernist musical elements, also remains both accessible and attractive. And Australia can also boast of having produced two of the finest exponents of the title role in Ronald Dowd and Stuart Skelton (who sang the role in the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s concert version in 2019).

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20CRUZ%20FITZ,%20(Peter%20Grimes)%20ALLAN%20CLAYTON%20ROH%20Peter%20Grimes%202022%C2%A9%20Yasuko%20Kageyama%20IMG_5458_1.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Allan Clayton as Peter Grimes and Cruz Fitz as the Boy in The Royal Opera's <em>Peter Grimes</em> (photograph by Yasuko Kageyama)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Allan Clayton as Peter Grimes and Cruz Fitz as the Boy in The Royal Opera's <em>Peter Grimes</em> (photograph by Yasuko Kageyama)

This production introduces another great Grimes to the operatic world, the English tenor Allan Clayton (best known to Australian audiences for his critically acclaimed performance as the title role in Brett Dean’s Hamlet for the Adelaide Festival in 2018). A co-production with Teatro Real, Madrid, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, and L’Opéra National de Paris, this Peter Grimes opened in 2021 in Madrid to critical acclaim. It is fully deserved; the production is an unequivocal triumph for both the creative team, led by director Deborah Warner, and the cast.

Warner abandons the original mid-nineteenth century Suffolk seaside setting (a thinly veiled allusion to Britten’s beloved Aldeburgh). She was, she claims, struck by a UK government finding that a township further down the coast in Essex was the location of the country’s ‘most deprived community’. No picture-postcard fishing village vistas here – this is a post-Brexit production, in which the English are much less sure of themselves or their place in the world.

This shift works because much of what Warner chooses thereby to emphasise is already implicit in the original. The town itself and the seaside it confronts are in many ways the principal characters of the work; a dramatic perspective heightened by the way Britten and Slater allow the drama to unfold as a series of cinematic tableaux.

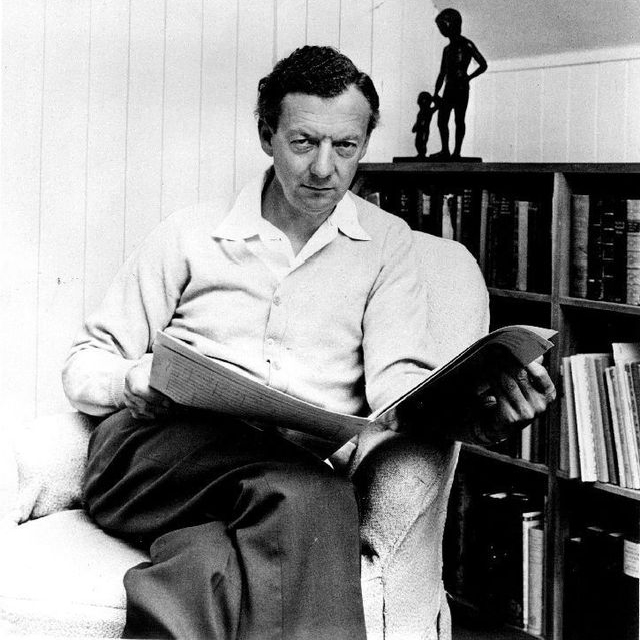

Benjamin Britten in 1968 (photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Benjamin Britten in 1968 (photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Here, set designer Michael Levine made full use of the capacious Royal Opera stage to present the illusion of a coast port, but was also able to create the requisite sense of physical (and psychological) claustrophobia in the pub scene. The addition of a flywire rigged doppelgänger of Grimes presented us with the premonitory vision that is haunting Grimes; his lifeless body first tossed by the waves, and then sinking beneath them. A large set backdrop of textured white material superbly illuminated by lighting designer Peter Mumford evoked the kinds of dancing light that appear on the sea itself. And in front of, and beneath, the set, conductor Mark Elder delivered Britten’s score with unwavering conviction, not least the six extraordinary orchestral interludes that frame these stage vistas.

Allan Clayton is simply outstanding as Grimes. This is his first but, one can safely predict, very much not his last stage performance of the role. He brought to it not only a technically assured, rich, and beautifully shaped tenor voice, but also clarity of diction and a constant concern with revealing the psychological depths of Grimes’s character. This was a performance of searing honesty and power.

Clayton is joined by a truly exceptional cast. Maria Bengtsson was an ideal Ellen Orford – her stage presence and voice alike well able to convey Ellen’s tragic combination of personal strength and vulnerability. Catherine Wyn-Rogers was a sympathetic Auntie, well supported by Jennifer France and Alexandra Lowe as her two mischievous nieces. Their quartet in Act II was one particular musical highlight among so many.

Bryn Terfel was in top vocal and dramatic form as Captain Balstrode: indeed, he seemed to relish every moment he was on stage. Likewise, John Tomlinson was, as one might expect, a charismatic and likeable Swallow. James Gilchrist (Reverend Horace Adams), best known outside Britain perhaps as the Evangelist in recordings of the Bach Passions, demonstrated how effective a vocal presence he also can be on the operatic stage. John Graham-Hall and Jacques Imbrailo were also hard to fault as Bob Boles and Ned Keene, respectively. Special mention should be made of the boy apprentice played by Cruz Fitz, who delivered a depth of emotional responses (notwithstanding his character’s muteness) that belied his age.

.jpg) Townspeople and fisherfolk of the Borough in The Royal Opera's Peter Grimes (photograph by Yasuko Kageyama)

Townspeople and fisherfolk of the Borough in The Royal Opera's Peter Grimes (photograph by Yasuko Kageyama)

For all its focus on these characters, the opera also has many great moments for the chorus (here judiciously and effectively deployed by choreographer Kim Brandstrup). They became an especially chilling lynch mob in the third act.

Britten himself wrote that the work was a study of ‘the individual against the crowd, with ironic overtones for our own situation’, by which he meant his and his lifetime partner Peter Pears’s stance as conscientious objectors (but also, no doubt, as homosexuals). As this production demonstrated, it is all these things, and more. Another great Grimes, the Canadian tenor Jon Vickers, stated that it was ‘a great opera because everyone who sees Grimes must go out of that opera with all kinds of misgivings about their attitudes to other human beings’. For that reason alone, the work deserves to be back on the Australian stage, and soon.

Peter Grimes is being performed at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, from 18 March to 1 April 2022.