- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Opera

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: La Juive

- Article Subtitle: Halévy’s rare and controversial opera

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

To say that Fromental Halévy’s opera La Juive (The Jewess) is a problematic work is a gross understatement. From the time of its successful première at the Paris Opéra in 1835 – it is one of the finest examples of French Grand Opera – it has been surrounded by controversy, periods of neglect, particularly during the 1930s, and even outright banning; its subject matter has been found confronting and frequently highly polarising. Although considered blatantly anti-Semitic by some, it was the finest opera of a successful Jewish composer.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Diego Torre as Eléazar and the Opera Australia Chorus in Opera Australia’s 2022 production of <em>La Juive</em> at the Sydney Opera House (photo by Prudence Upton)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Diego Torre as Eléazar and the Opera Australia Chorus in Opera Australia’s 2022 production of <em>La Juive</em> at the Sydney Opera House (photo by Prudence Upton)

Halévy was born in Paris in 1799 and died in Nice in 1862. His father was a cantor and scholar from Germany, and his mother came from Nancy; both were Jewish. Young Fromental showed early musical promise and became a student of Italian Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842) at the Paris Conservatoire. Cherubini – composer of Médée and many other operas (1797) – guided his career with insight, care, and considerable influence. Halévy became part of the French musical establishment as teacher and administrator; his pupils included Gounod, Bizet, and Saint-Saëns. His daughter married Bizet, while his brother Léon’s son, Ludovic, was the successful librettist of Carmen, Orpheus in the Underworld, and many other works.

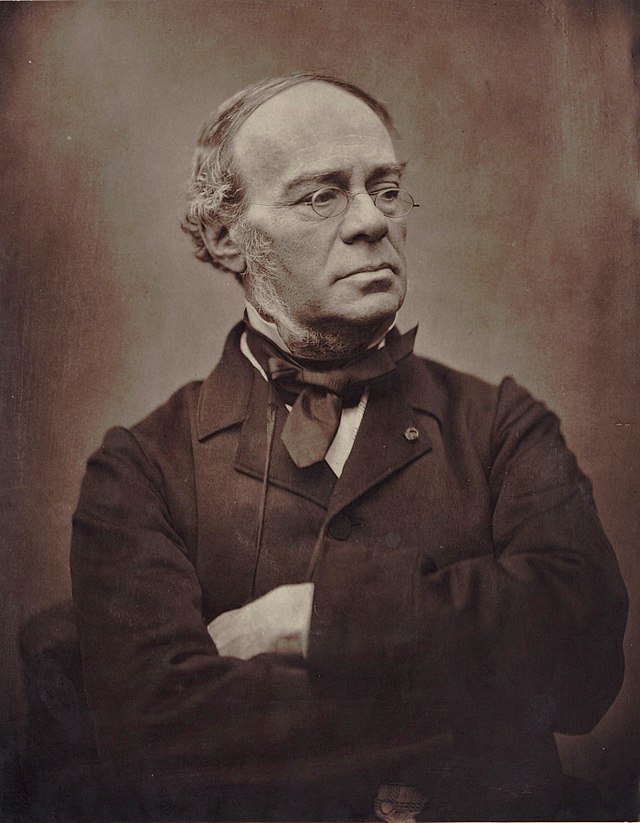

Photograph of Fromental Halévy by Étienne Carjat (courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons)

Photograph of Fromental Halévy by Étienne Carjat (courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons)

The other central figure is Eugène Scribe, one of the most significant librettists of the nineteenth century, who provided texts for composers such as Meyerbeer, Bellini, Verdi, Donizetti, Rossini, and others. His libretti constitute the foundation of the French Grand Opera genre and influenced the course of European opera during the rest of the century. Many of these libretti are inherently political in nature, despite Scribe’s apolitical protestations (a stance belied by his anti-clerical views). Scribe intended the La Juive libretto for Meyerbeer – at the time the most successful opera composer in Europe – but when he declined Scribe turned to Halévy, who later remembered the occasion:

It was a beautiful summer evening in Montclair Park when M. Scribe first told me the subject of La Juive, which moved me very deeply. I shall always remember this conversation, which was associated with one of the most interesting epochs in my life as an artist.

Halévy’s relationship with his own Jewishness has been much debated, but there is evidence of an extensive and deep involvement in the Paris Jewish community which, during his adolescence, was gradually being integrated into French society, while simultaneously confronting the inherent challenge of reconciling their Frenchness and Jewishness.

There are strong links between La Juive and Meyerbeer’s popular Les Huguenots (1836), also with a libretto by Scribe. Both deal with religious intolerance and persecution; Les Huguenots with Catholic and Protestant conflict, while La Juive presents a similar clash between Judaism and Christianity. The central Jewish figures of Éléazar and his daughter Rachel – the Jewess – are complex, while the depiction of a Passover service, the religious confrontations, and the death sentences passed on Éléazar and Rachel, are bound up with the centuries-old conflicts between Christian and Jewish communities, reflecting issues pertinent to contemporary France. The tragic irony at the centre of the opera is that Rachel is the long-lost daughter of the Cardinal Brogni. She dies a martyr, believing she is Jewish. Éléazar’s portrayal has frequently been regarded as a virulently Shylock-type, anti-Semitic caricature, despite the great revelation of his deep love for his daughter and his sense of tragedy in the celebrated Act IV aria, Rachel, quand du seigneur.

Opera Australia’s co-production with Opéra National de Lyon premièred in 2016 as part of the Festival pour l’Humanité. Originally scheduled here for 2020, it was an early victim of Covid, so it is very welcome that it has finally made it to the Sydney Opera House, despite being threatened by the Sydney floods. The work was last staged in Sydney and Melbourne in 1874. Oliver Py’s production, restaged here by Constantine Costi, is set in France in the 1930s, when the opera largely disappeared from European stages.

There are many elements in the striking designs and costumes by Pierre-André Weitz that foreshadow the looming Holocaust, including book burning and the display of racist banners. There is prominent use of Jewish iconography. The final moments are particularly striking: the crashing down of piles of shoes a moment of sheer horror, followed by a group of men trudging off to what seem like gas chambers. The colours are predominantly grey and black, dominated by a bleak, ravaged landscape with dead trees visible through rising smoke. Certainly, there is little similarity to the Paris première which demanded twenty horses and more than 300 extras on stage in a spectacle that astounded and divided the somewhat jaded Parisian audiences.

A strong cast has been assembled. There are five significant principal roles headed by Natalie Aroyan as Rachel. In recent years, Aroyan has become a stalwart of the company, but she has suffered more than most because of cancellations over the past two years, so it is to be hoped that she has a clear run as Rachel. Her voice has a refined, rich quality and is even throughout the range. Written for the celebrated French singer Cornélie Falcon, the role calls for a strong lower and middle register, and a radiant upper extension. The term ‘Falcon’ is sometimes used for this type of voice which has a mezzo quality but a soprano range. There were many highlights in Aroyan’s portrayal. Performed within a huge Star of David, the great Act Two aria, Il va venir, as Rachel waits for Samuel, will remain etched in the memory, as will the passionate duet that follows. Aroyan goes from strength to strength with each new role she assumes.

Natalie Aroyan as Rachel in Opera Australia’s 2022 production of La Juive at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Natalie Aroyan as Rachel in Opera Australia’s 2022 production of La Juive at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Diego Torre is her father, Éléazar, the goldsmith-jeweler, having recently portrayed her lover in both Ernani and Attila by Verdi. In many ways, it is an unsympathetic and controversial role, notwithstanding Éléazar’s beautifully expressive music. A highlight of the score is the restrained and moving Passover scene in Act Two, which is led by Éléazar. Torre did it full justice, with some finely judged soft singing and expressive phrasing. The great aria in Act Four also had pathos and humanity, and he both physically and vocally conveyed the torment at the heart of the character. This is an outstanding performance; it is difficult to think of any role he has sung with more beauty and expressivity in his long and distinguished association with the company.

David Parkin has the required sonorous bass quality for the role of the anguished and vengeful, yet empathetic Cardinal Brogni, another character who is required to display a wide emotional range. His celebrated Act One aria of compassion and forgiveness, Si la rigeur, had a lyricism and well-supported legato line, and he certainly possesses the notes at the bottom of the stave that this role requires. The voice has a velvety darkness and it is a shame that audiences in Australia don’t hear him in more roles of this stature.

Unusually for grand opera, a second large tenor role, Prince Léopold, disguised as Samuel the painter, is required. It was sung by Argentinian Francisco Brito, who has a lean and flexible tone. His impassioned exchanges with Rachel were emotionally convincing. The role lies high, with several top Cs, but his voice was equal to all that Halévy could throw at him.

Esther Song’s bright voice as Princess Eudoxie contrasted well with the more lyrical tone of Rachel. Eudoxie is a somewhat ungrateful, flighty character, but Song sang expressively, the challenging coloratura negotiated with aplomb and spirit, bringing out the humour and extroverted quality in the role. Her scene with Rachel, when they both discover their shared humanity, was especially moving. Andrew Moran, Richard Anderson, Shane Lowrencev, and Alexander Hargreaves all provided strong performances in the smaller roles.

Carlo Montanaro conducted the orchestra with a clear understanding of style and nuance. The score is full of variety of colours and textures, and Montanaro kept a sense of momentum and shape throughout, even when Halévy might be accused of note-spinning. The big choral scenes showed great control of balance, projection, and dynamics, and Montanaro was always sensitive to the emotional contours of the many intimate, conversational scenes. The chorus is prominent, and Opera Australia’s brilliant singers consummately conveyed the varying and sometimes terrifying moods and mob mentality demanded by the plot.

Despite his virulent anti-Semitism and bitter resentment of the Paris operatic establishment, Richard Wagner was a great admirer of La Juive’s ‘verve and refinement’, arguing, with typical racist bias, that Halévy was ‘frank and honest; no sly, deliberate swindler like Meyerbeer’, and that he had ‘never heard dramatic music which has transported me so completely to a particular historical epoch’. Cosima Wagner’s diaries reveal that Wagner ‘kept a score handy and every now and then would reach out for it and call his visitors’ attention to some particular quality he admired in it’.

The opera’s recent revival should partly be attributed to the American tenor Neil Shicoff, who sang the acclaimed first performance of the important production by Günter Krämer in Vienna in 1999. The opera’s success, and particularly the presence of Shicoff, a great favourite in both cities, encouraged the Metropolitan Opera in New York to stage it in 2003, the first time for nearly seventy years. Éléazar had been a signature role of the great Enrico Caruso; it was his last performance at the Met before his death in 1921.

In several interviews and discussions at the time of the New York première, Shicoff, the son of a cantor, specifically linked the opera to his own Jewish background, highlighting the personal and political resonances of the opera, claiming that it was ‘the most contemporary political opera there is’. This, of course, tapped into the powerful collective Jewish experience of New York residents, the centre of American Jewish life, culture and, most importantly, Holocaust memory. There was great media interest, with Shicoff happy to discuss his relationship with the opera, while the production provoked much controversy.

As Rachel Orzech has observed: ‘By drawing on the American preoccupation with Holocaust memorialization, Shicoff linked the Jewishness of the opera, and his part in it, with Jewishness in contemporary American life.’ Shicoff commented on the highly political nature of the opera, suggesting that Rachel might be portrayed as a suicide bomber. This was taken up literally in a typically radical production by Peter Konwitschny, in Antwerp in 2015, with Rachel at one point wearing a suicide belt.

It is to Opera Australia’s great credit that this important work has been staged in Australia in this haunting and thought-provoking production. Diana Hallman has observed that the opera’s

warning of the dangers of blind intolerance and the despotism of governments and religious powers, and of the perils of seeking righteousness through the crushing of perceived enemies is just as pertinent in the twenty-first century as it was in 1835.

Despite the widely diverging views and attitudes towards the opera, it is a flawed, demanding, highly significant work that calls for great imagination in staging and outstanding performances, while adding to the breadth of the operatic canon. It is an occasion that will linger long in the memory.

La Juive, presented by Opera Australia, continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House, until 26 March 2022. Performance attended: 9 March.