- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fun Home

- Article Subtitle: Bechdel’s touching testament to queer love

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Vladimir Nabokov, in his exquisite autobiographical work Speak, Memory (1967), says that ‘the prison of time is spherical and without exits’. It is an idea that animates Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron’s musical adaptation of Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home (2006), moving as it does in circular motions, enfolding its characters in an endless orbital spin through the years. Perhaps memory itself is like this, forever returning to our consciousness the painful and joyous things we’d thought we’d left behind, like moons in retrograde. It is no accident that the show’s opening number is titled ‘It All Comes Back’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

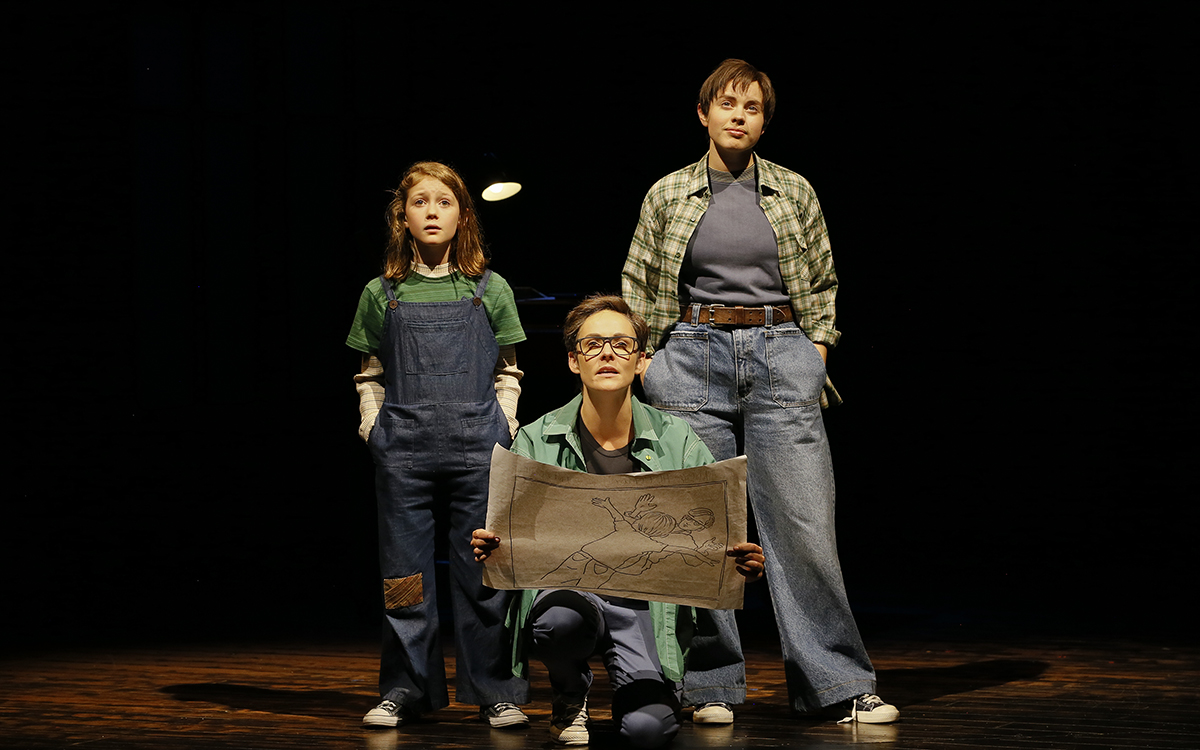

- Article Hero Image Caption: Photograph by Jeff Busby

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Photograph by Jeff Busby

Bechdel’s acclaimed work focused on her complex, highly fractious relationship with her father, Bruce. Kron’s book and lyrics are forensically concentrated on the shifting dynamics between father and daughter, as well as the tectonic implications of his suicide. One of the musical’s chief assets is its selectivity, the way it knows exactly what to include and what to leave out. The result is a prismatic and moving portrait of a family in crisis that also has much to say about the quicksands of sexual identity and the legacy of lost queer lives.

While Bechdel is now quite famously a proudly out lesbian – she created the long-running comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, and was responsible for initiating what is known as the Bechdel test, which tracks female representation in film – her father threw himself in front of a truck rather than deal openly with his own homosexuality. The narrative of coming out, the way popular culture tends to reduce it to a rags-to-riches tale of self-actualisation, is here tempered with the bitterness of failure. As Bechdel says of her father in the song ‘Maps’, ‘I can draw a circle you lived your life inside.’

Fun Home has three iterations of Bechdel on stage, often at once. There is the adult cartoonist looking back (an excellent, frazzled, but determined Lucy Maunder), the college student finding and embracing her queer identity (Ursula Searle, sublime), and the child of ten (played winningly on opening night by Sophie Isaac), deeply connected to a father she nevertheless fails to understand. On Alicia Clements’s gorgeously designed revolve, the three Alisons swirl around each other, passing the baton of memory back and forth as they try in their own distinct ways to unlock the mystery of their father’s recalcitrant personality. Adam Murphy plays Bruce with an explosive mix of charm, reticence, rage, and narcissism; while there may be a void at the heart of this man, he never feels less than vividly human.

One of the key delights of Fun Home – cited as the first mainstream musical to feature a lesbian as the central protagonist – is the way it leavens its thornier moods with some beautiful and poignant scenes of sexual awakening. Middle Alison’s adventures with fellow student Joan (Emily Havea, wonderfully droll) are endearingly awkward, and Searle, plaintive and direct, often threatens to walk away with the whole show. The song ‘I’m Changing my Major (to Joan)’ is a standout, a paean to first love that is so authentic it could only have come from lived experience. These elements of joy don’t just sit alongside the tragic impulse of Bruce’s self-denial, they actively underline it. As Alison embraces her sexuality, integrating her desires into her larger personality, Bruce contracts and diminishes, growing ever more desperate, furtive, and malign.

Director Dean Bryant does a magnificent job corralling the work’s disparate elements into a unified whole; he allows each character to shine – from Silvie Paladino’s heartbreaking confession of agony ‘Days and Days’ to Euan Fistrovic Doidge’s showstopper ‘Raincoat of Love’ – without ever letting the audience forget that it is Alison’s relationship with her father, in particular the way their sexuality impacts on each other, that is the main game. The pacing is expert, with long sweeping scenes of family chaos and clamour abutting short, sharp scenes of sudden rage and bitterness. Clements’s set is vital to this effect, a flexible playground for the actors that also brilliantly reveals character. This is a fun home, a funeral home, and also a prison.

In some ways, Fun Home is more of a serious play with songs than a standard musical, which in no way diminishes its effect. Tesori’s music and Kron’s lyrics occasionally tilt knowingly towards Broadway excess, but mostly they have a haltered, reticent quality that is in perfect keeping with Bechdel’s own persona, not to mention the lurching, syncopated rhythms of memory itself. This excavation of a father’s flaws is emotionally harrowing, and the show’s form – the way it blends dialogue with singing, the way songs tend to either end abruptly or peter out – feels like a natural extension of its content.

At the beginning, Alison says ‘I need real things to draw from, because I don’t trust memory.’ This is a statement of process – Bechdel famously uses photographs as artistic aids and, when they aren’t available, recreates scenes from life with herself as model – but also a profound acceptance of the unreliability of personal perspective. Bruce was many things to his family members, tyrannical and tender, cutting and kind, but he was also many things Bechdel can’t ever know. Portraiture is, by design, an imperfect, imprecise art form, and Fun Home understands this deeply. It isn’t enough to command memory to speak, as Nabokov would have it; you have to draw it out and put it down on paper, shift the outlook, rearrange the pictures, and even then the results will be tainted by your own pain and joy.

Fun Home is a superb night in the theatre and, perhaps most significantly, a testament to queer love in all its beauty and terror. Young Alison opens the play wanting ‘to play airplane’, stretching her body to full length balanced on her father’s legs. It is a typical childhood pleasure, but it also stands as a powerful image of intergenerational queer solidarity. Bruce may have suffered deep shame and repression, and ultimately died because he couldn’t accept himself, but he also raised a gloriously proud, out gay woman. It is a reminder that all queer people stand on the shoulders of giants, and that all social progression is dusted with the ash of those who perished along the way. All we can do is honour them, and remember.

Fun Home is being performed at the Playhouse in Melbourne’s Arts Centre from 7 February until 5 March 2022.

This review is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.