- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen

- Article Subtitle: An expansive retrospective on a prodigious artist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

With its title, William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen, an exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery, signals two prongs of the politics of vision: the power of the gaze and the importance of representation, an apt framing for an artist who has been invested in both for more than fifty years. As a substantial and generous retrospective, curated by Rosie Hayes, it threads together the distinct but connected themes of Yang’s practice: queerness, particularly the queerness of gay men; Chinese-Australian identity and experience; the Australian landscape; and the art, film, and literary scene in Sydney.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

2008_Artist_001.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: William Yang, Australia, 1943, <em>William in Cane Fields</em> (from ‘My Uncle’s Murder’ portfolio) 2008, Inkjet prints on Innova Softex paper, 59 x 91cm, Collection: The Artist © William Yang (photograph by Jenni Carter)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): William Yang, Australia, 1943, William in Cane Fields

- Production Company: QAGOMA

Many of Yang’s photographs are inscribed with handwritten text, the prose of which is both crystalline and intimate, almost guileless. In a 1974 family portrait, striking in both its formal beauty and the awkwardness of its sitters, he writes that his father died not long after, closing the passage simply: ‘I was not close to my father.’ Yang is best known as a photographer, but his work often hinges as much on its written content, as well as on the dialogue between the written and the visual. Roland Barthes suggests that photography’s spatial information is past tense; it creates ‘a new space-time category: spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority.’ Yang’s inclusion of text complicates this assertion because it introduces other temporal elements. One is the nostalgic voice of the artist, always itself past tense, but more recent than the image he made, or is commenting on. The other is the viewer’s sustained attention as they not only look, but read, in the now. This was particularly evident encountering so much of Yang’s work at once; to meaningfully engage in this show is to invest it with your time.

William Yang, Australia, 1943, Alpha, late 1960s, gelatin silver photograph with fibre-tipped pen on fibre-based paper, ed. 6/10, 26.7 x 40.2cm, © William Yang, Purchased 2001, Collection: The University of Queensland

William Yang, Australia, 1943, Alpha, late 1960s, gelatin silver photograph with fibre-tipped pen on fibre-based paper, ed. 6/10, 26.7 x 40.2cm, © William Yang, Purchased 2001, Collection: The University of Queensland

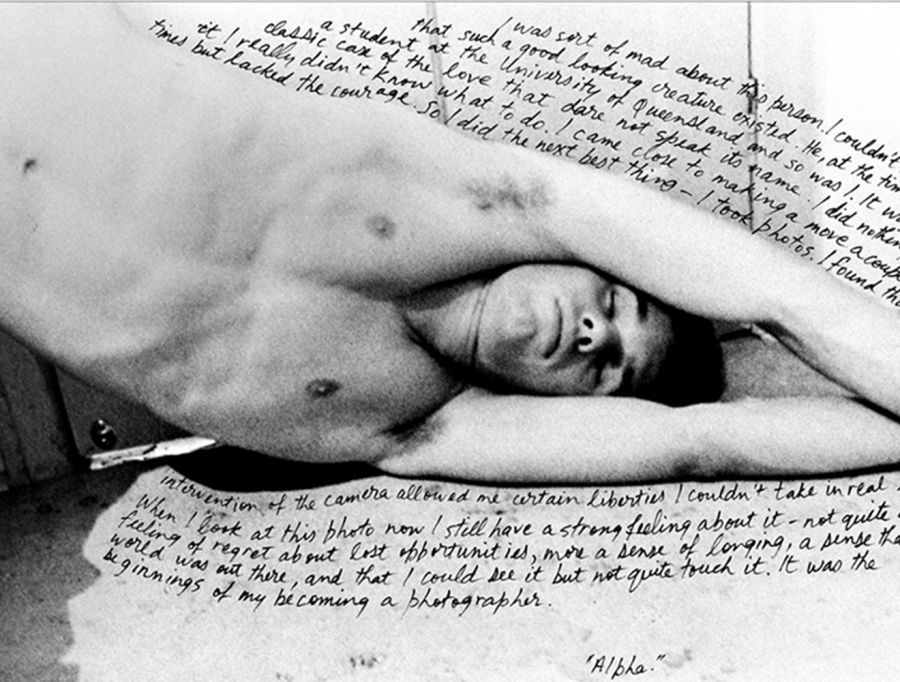

All photography is nostalgic according to Susan Sontag: ‘[p]recisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt’. In Yang’s work, text amplifies this quality, affecting an elegiac tone. Showing alongside a selection of portraits of gay men, often on beds, half or fully naked, is an early photograph, Alpha (late 1960s). Taken while Yang was a student at the University of Queensland, it is exemplary of this quality. A beautiful young man has his eyes closed, arms stretched above his head like he’s diving, the curve of his torso, neck, head reaching down through the image, which crops him at wrists and hips. Text eddies around his body, recalling Yang’s awe for his beauty, the artist’s desire and fear:

I found that the intervention of the camera allowed me certain liberties I couldn’t take in real life. When I look at this photo now I have a strong feeling about it … a sense of longing, a sense that the world was out there, and that I could see it but not quite touch it. It was the beginnings of my becoming a photographer.

Yang leverages photography’s relationship with longing and loss to represent both desire and death to moving effect. One of his best-known series, part of the Sadness project, documents the decline of his friend Alan as he succumbs to AIDS. The photos are tender and direct; as Alan gets closer to death, and then dies, Yang does not flinch. Two of the last images of Alan call to mind David Wojnarowicz’s deathbed photo of Peter Hujar; he too had died from AIDS. Alongside the images of Alan are two memorialising diptychs comprised of photos taken during candle-lit vigils for victims of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Vigil (1994) is framed more closely; grave faces glow in the crowd. In Names (1992), Yang takes a wider view, candlelight scattered through the gathering like stars, and across the entire surface the handwritten names of the dead.

Yang’s most potent work tends to be emotionally demanding, but his playful side is well represented in the exhibition. His glossy, idealised photos of men at the beach and raucous society pictures, as well as a set of Mardi Gras photos, will be a joy to viewers, expanding the myriad rewards of this exhibition of one of Australia’s most significant and enduring artists.

William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen is showing at the Queensland Art Gallery until 22 August 2021.

This review is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.