- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Joan Mitchell: World of Colour

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Joan Mitchell: World of Colour

- Article Subtitle: A revealing exhibition at the NGA

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The American Joan Mitchell is one of a legion of celebrated twentieth-century artists with a ghost presence in this country. Since her death in 1992, her vibrant, energetic paintings have become increasingly appreciated, and now her star is rising again. This year Mitchell is the subject of a major retrospective in the United States, which will also be seen in Paris in 2022. The National Gallery of Australia’s current exhibition is part of the year-long Know My Name suite of projects. An outcome of the NGA’s long relationship with master printmaker Kenneth Tyler, Joan Mitchell: World of Colour, led by emerging curator Anja Loughhead, is the first exhibition anywhere to focus solely on Mitchell’s prints, which were made in two concentrated bursts with Tyler, in 1981 and again in 1992, just before the artist’s death.

- Production Company: National Gallery of Australia

Lithography is the most immediate and painterly of print media, a sort of poor woman’s painting, and together Tyler and Mitchell developed an innovative technique that suited her painting processes. These works are simply glorious, hugely pleasurable, with overlays of bold strong strokes and splodges of colour that speak to, and evoke, landscapes and gardens, both at Mitchell’s home in Vétheuil, north-west of Paris, and in Bedford Village in upstate New York, where Tyler’s print workshop was located. Here, colour and line are always one; Mitchell’s choices are confident, assured – the colours seem to float free over the white paper, rich, sensuous, knowing. The magnificent Tree II (1992) is a case in point: brilliant strokes, squiggles and smudges of orange, viridian, and ultramarine bloom on the black architecture of the tree, which has been summoned from close looking and long memory. It’s a contemporary Tree of Life, ecstatic with promise. And colour is the core of this life: catalogue essayist Sally Foster quotes Tyler from 1992: ‘I never worked with anyone since [Josef] Albers that had such a keen knowledge of colour and how colours interacted with each another.’

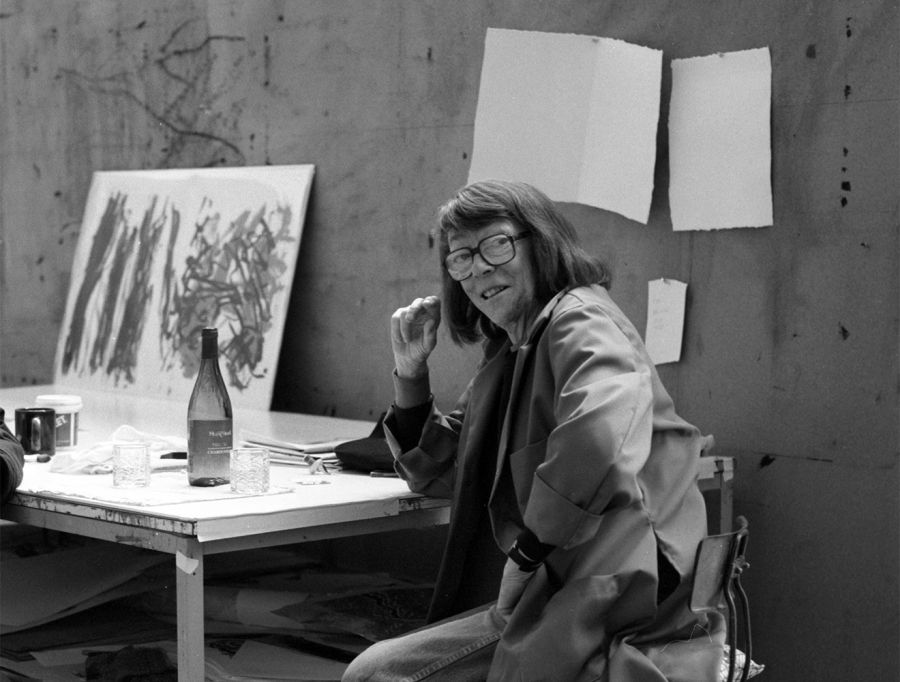

Joan Mitchell at Tyler Graphics Ltd., Marabeth Cohen-Tyler, Mount Kisco, New York State, 1992 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra gift of Kenneth Tyler 2002

Joan Mitchell at Tyler Graphics Ltd., Marabeth Cohen-Tyler, Mount Kisco, New York State, 1992 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra gift of Kenneth Tyler 2002

While Mitchell’s works are animated by bold colours and an assertive physical working of them, she was always strictly in command of her making: this is studio art, not performative Abstract Expressionism. Now we know from photographs, and the video included in the exhibition, that Mitchell worked methodically, fastidiously: more than half the catalogue is devoted to photographs of the artist’s processes, her working relationship with Tyler and Marabeth Cohen-Tyler, and her garden and landscape subjects in France.

Despite, or perhaps because of this control, the effect of these large generous prints is a wonderful feeling of expansion: air is taken into the lungs. Sides of a river III is particularly beautiful, in its sparseness and delicate colour, so much so that I don’t believe it requires bracketing with a Willem de Kooning painting and a pair of far earlier Kandinsky prints, from 1922, the latter a gesture to twentieth-century abstraction that goes unargued. The insertion of contextual works by other artists is, however, more pointed: prints by Franz Kline and de Kooning, plus the diminutive figurative de Kooning sculpture, nicely make the point that Mitchell and her contemporaries did, in fact, look to the visible world for sources for their art.

And yet … the presence here of de Kooning’s 1968 painting Two figures in a landscape, acquired in 1973, serves to highlight that there is no painting by Joan Mitchell in the NGA collection. So where does her work sit in the gallery’s great holdings of postwar and contemporary American art? These are now skewed by the strength of early acquisitions and patchy attention over recent decades. In drawing attention to an important American artist who had been overlooked in the NGA’s pantheon, except for excellent print acquisitions and as part of a huge gift from Tyler, the NGA curators have essayed something of an institutional auto-critique. I welcome it. The great acquisitions of the early decades (including major paintings by Lee Krasner and Helen Frankenthaler) were, as numerous commentators have pointed out, squarely in line with the credo of influential American critics, particularly Clement Greenberg, who argued for Abstract Expressionism, then reductive Colour Field painting, as the authentic (orthodox) form of modern art. The Know My Name context reveals the undoubtedly gendered aspect of Mitchell’s relegation to a second-tier practice that admitted visual references and that was not (ostensibly) improvised and performative.

Sides of a river II, 1981, Joan Mitchell, from the ‘Bedford’ series, 1981 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002 © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Sides of a river II, 1981, Joan Mitchell, from the ‘Bedford’ series, 1981 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002 © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Mitchell was very aware of her situation – how could she not be? Her biographer, Patricia Albers, quotes her saying ‘Not bad, huh, for a woman?’ during a studio pause, and Mitchell says on a posthumous 1993 documentary film: ‘They call me “sauvage” in Europe because I am direct, and I say what I think ... and you aren’t supposed to. You’re supposed to be diplomatic which I call hypocrisy and lying really. Lots of things women can’t be ... “sauvage” is one of them.’

Mitchell’s wry comment alludes to her living between the United States and France, from 1955 to her death. As Loughhead points out, Mitchell was always something of an ‘outsider’ in the mainstream art worlds of both countries. Living in rural France, evading Greenberg’s long shadow, Mitchell made beautiful works alluding to the physical world, to things seen, to a ‘remembered landscape’, in Mitchell’s own phrase. They revisit, they distil, variously, a Flower, Sides of a river, sunflowers; some are named for locations, and several series of trees embrace many arboreal forms.

I am grateful for an afternoon spent with these wonderful works, measuring my length against Mitchell’s bold lines, slipping into the spaces where they criss-cross. But I want more. I miss seeing the prints together with the National Gallery of Victoria’s painting Marge (1990), currently on display in Melbourne. This major work from the period when Mitchell was working with Tyler would have expanded an understanding of her art; perhaps budgetary constraints prevented the NGA from borrowing it. So a gentle prod: these prints are ravishing, but with Joan Mitchell: World of Colour the NGA has opened a Pandora’s box. Now I want to see a major painting by Mitchell in Canberra, fully revealing the exquisite lyricism of her idiosyncratic abstract painting. Now we know the name, we want to see the entirety of Joan Mitchell’s world of colour.

Joan Mitchell: World of Colour continues at the National Gallery of Australia until 26 April 2021.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.