- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Tim

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone,’ wrote the seventeenth-century writer Blaise Pascal. As many of us are discovering, doing nothing alone in a room is a surprisingly difficult and demanding task. Even in these unusual times, when we are being asked – or in some cases, legally required – to stay home and do as little as possible, we are bombarded with suggestions as to how we might fill this sudden excess of time. We can stream a classical concert, watch sea otters floating in distant pools, binge-watch the latest drama series on Netflix, try out ballet fitness routines in our lounge room, or (my chosen method) try to learn the ukulele. And then what? As Pascal knew (even without the benefit of YouTube or TikTok), the easier it is to distract ourselves, the more restless we seem to end up feeling.

- Production Company: Museum of Old and New Art

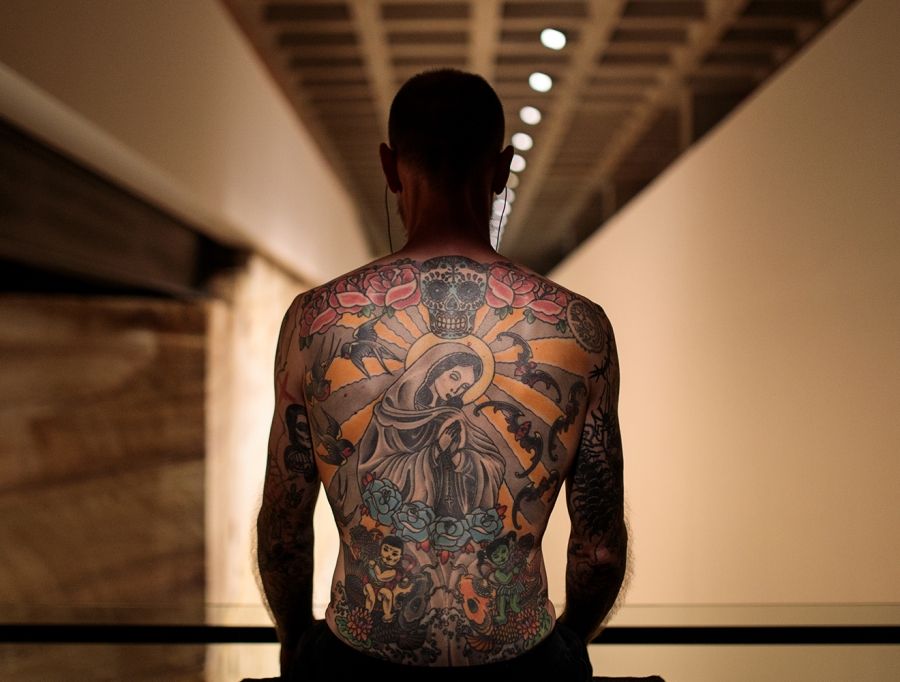

Tim Steiner (photograph courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania)

Tim Steiner (photograph courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania)

Despite MONA temporarily closing its doors on 17 March 2020 in response to the Covid-19 crisis, Steiner continues to sit – alongside other works of art – on a mezzanine overlooking the Void, a subterranean space framed by slabs of Triassic sandstone. A live stream has been set up to record Steiner’s every breath and movement, from 10 am to 4:30 pm. The idea of thousands of self-isolating people watching someone sitting quietly alone in a room seems perfectly in keeping with MONA owner David Walsh’s darkly ironic sense of humour. ‘Of course! How very MONA,’ one of my friends smirked when I told them about the live stream, MONA having become a uniquely Tasmanian synonym for anything quirky, weird, or absurd. I clicked the link to confirm that the video really was live, and not just a static image of Steiner’s back on a loop (yes, he gets up occasionally for a toilet break). I watched intently for a full five seconds before my attention slid away to the next email.

Yet as the long days of self-isolation wore on, I found myself returning to Steiner (or rather, back to his back). There was something oddly comforting about his presence, his persistence, his endurance. Although he sits as still as any sculpture, his skin glows with animate heat. The tattoos are too faint to make out clearly in the half-light of the sandstone walls, apart from a large Madonna kneeling above his spine and a Mexican-style skull grinning between his shoulders. At first, the experience of watching Steiner on live-stream seemed less about inspecting the artist’s handiwork than about the audience’s own voyeuristic gaze. We often go to museums and art galleries to stare at inanimate (and often naked) human forms, but watching Steiner sit for hours on end is an unusually intimate experience. Perhaps because, unlike a statue or a painting, Steiner could decide at any time to get up and walk away.

I wondered what habits of mind Steiner had cultivated to keep coming back to his plinth of self-isolation. In an ABC interview from 2017, Steiner described a typical day: he arrives at the museum several hours before opening time, does some yoga, meditates, and stares at the other works of art around him before assuming his position on the plinth. Occasionally, he might listen to music on headphones, but for the majority of the time he sits there in silence.

‘Every hour sucks on that box, believe me!’ he laughed. Try sitting motionless on your desk for five minutes, let alone five hours, and you’ll see what he means. ‘My body is in a state of pain all day long … At the end of the day I’m broken physically and mentally, I can barely speak. It’s like I run a marathon in my head every day.’ And yet, he says, he loves his job. ‘Doing nothing all day is the hardest, most challenging, most rewarding, most overwhelming thing I’ve ever done ... it’s discipline. We live in a world where everything is about choice, [but for me] there is no choice, I have to sit on that stupid box five hours a day or I lose my job. So taking the element of choice out and just forcing myself to do this, I’m starting to come out on the other side of a very long, dark, challenging tunnel. And there’s a lot of light here. I’m still not there yet, but I’m on the way.’

According to Walsh’s March 30 ‘COVID-19 Diary’ entry on MONA’s website, Steiner did have a choice about whether to continue sitting in the museum after it was closed to the public. He asked to keep sitting. ‘I was flabbergasted,’ Walsh wrote. ‘I shouldn’t have been. It’s his job.’ But why would someone show up to a job that he himself described as mental and physical torture? Steiner’s answer offers all of us a ray of hope for our current situation. ‘Being locked down on this box every day has made me really, really free, in spirit and in mind ... It has taught me that in life it really doesn’t matter what you do, it matters how you feel about it and how you approach it.’

Aware that with every passing hour, day, and year his body’s canvas ages, the tattoo colours fade, and his mortal ‘frame’ becomes more scarred and worn, Steiner has gained a different perspective on time, mortality, and the nature of existence. ‘In this world of ridiculous speed and unbelievable complexity, I’ve just realised... it’s about simplicity. It’s about minimizing.’ From his front-row seat above the Void, Steiner’s body radiates a reassuring message. ‘It’s weird to say, [but] ... our existence is perfection.’

Tim (MONA), by Wim Delvoye, was live-streamed from MONA in March 2020.