- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Assembled: The Art of Robert Klippel

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

TarraWarra Museum of Art’s (TWMA) summer exhibition Assembled: The Art of Robert Klippel can only reinforce his reputation as Australia’s foremost modern sculptor. Yet he lacks the public reputation of his contemporary painters – John Olsen, Fred Williams, John Brack, and so on. Klippel (1920–2001) is known largely, if not exclusively, to the world of art. This exhibition may right that historic injustice. Thoughtfully curated by Kirsty Grant, it brought the three basic streams of his art – the drawings, the metal sculpture, and the monumental wood works of his final phase – into a crisp and clear narrative.

- Production Company: TarraWarra Museum of Art

In Paris Klippel met André Breton, the Pope of Surrealism. Perhaps more importantly, he saw Joan Miró’s major postwar exhibition at Galerie Maeght. Miro had just completed his Constellations, in which drawing played a major role. They combined substance with a lingering sense of automatism, the hand playing at will across the sheet. Klippel seized on them as a way forward. The early drawings frequently have a sculptural frame on which free-floating shapes accrete. Collage became second nature to him as a draughtsman. The two-handed nature of collage, cutting, or tearing the shapes and then attaching them to a flat sheet, is essentially a sculptural procedure.

Robert Klippel in his Potts Point workshop, 1957 (photograph via TarraWarra Museum of Art)

Robert Klippel in his Potts Point workshop, 1957 (photograph via TarraWarra Museum of Art)

When Klippel returned to Sydney in 1950, he was arguably the best informed and most accomplished abstract artist in the country. He knew leading artists in London such as William Turnbull, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Alan Davie, and, in Paris, Jean-Paul Riopelle and Nicolas de Staël. Furthermore, he had exhibited successfully in both cities.

Sydney in the early 1950s was a backwater. Klippel exhibited with Ralph Balson, then the most widely admired abstract painter in Australia, without eliciting a single sale. Klippel returned to full-time work for his family’s textile business, grateful for their support during the Paris–London years. The desultory art scene took its toll: he made just eighteen sculptures in 1950–57. Klippel, presciently, broadened his sculptural technique during this fallow period. He returned to the East Sydney Tech and learned welding and other metal-making skills.

Kirsty Grant notes that during this period Klippel shifted his interest from Europe to America. When he left Australia again in 1957, it was for New York; eventually he found a teaching job in Minneapolis. He saw David Smith’s retrospective at MoMA and, crucially, met the American sculptor Richard Stankiewicz, the pioneer of using junk metal as sculptural material. Klippel, whose earlier work had largely been carved in stone or wood (and very accomplished it is), now became exclusively a sculptor in metal. He transformed discarded, industrial metalwork into a fluent and expressive sculptural form.

Robert Klippel, No. 247, metal construction, 1965–68, welded and brazed steel, found objects and wood, 269 x 145 x 126 cm. Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. Purchased 1983. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation © Andrew Klippel. Courtesy of The Robert Klippel Estate, represented by Annette Larkin Fine Art, Sydney and Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich / Copyright Agency, 2019.

Robert Klippel, No. 247, metal construction, 1965–68, welded and brazed steel, found objects and wood, 269 x 145 x 126 cm. Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. Purchased 1983. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation © Andrew Klippel. Courtesy of The Robert Klippel Estate, represented by Annette Larkin Fine Art, Sydney and Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich / Copyright Agency, 2019.

Klippel supersedes others in the field of junk sculpture by disguising so completely the origins of his materials. The driving rhythms of his metal work eliminates any past associations his material may have. The sculptures have a strangely organic quality to them – the opposite of their actual nature. In 1965 he made a sculpture from cogwheels so densely accreted (rather than assembled) that they have the effect of a coral strand, ironic and beautiful.

The welded metal sculptures continue unabated throughout the 1960s and 1970s. They were products of ‘cog and bud’, as Klippel liked to describe them. They show an ease and spontaneity, clear indication of his mastery over his materials. And then, circa 1980, came the great change to his art. Klippel switched from metal to wood. Like the metal sculptures, it was discarded junk. Sometimes painted, the new material had a clumsy quality and effect, sometimes comic, sometimes mysterious.

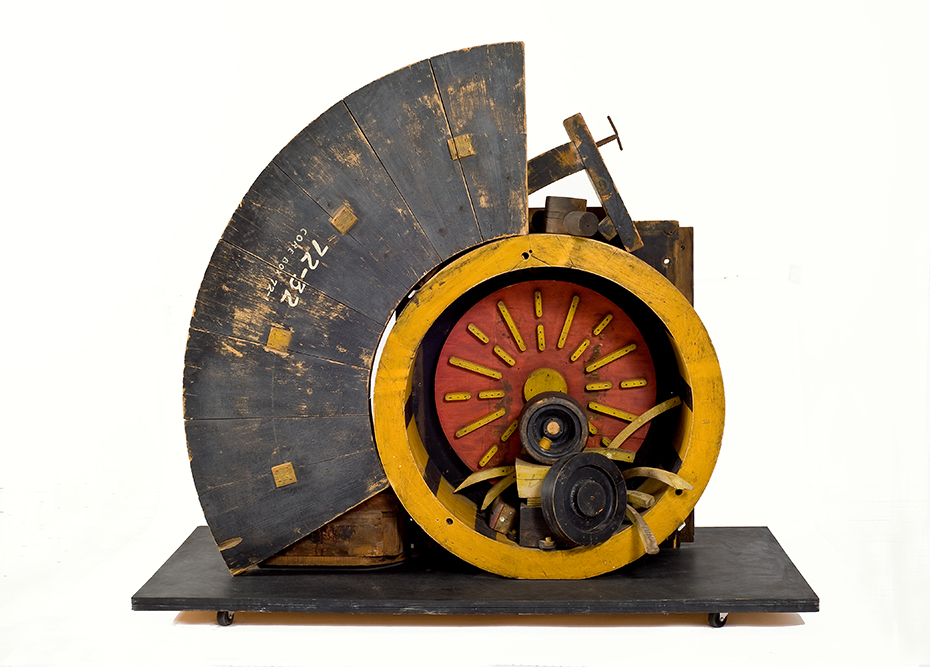

The origins of this astonishing volte-face go back to 1964, according to Kirsty Grant, when his friend and fellow artist Colin Lanceley discovered in the abandoned Balmain office of an old engineering firm a basement packed with ‘thousands of obsolete dusty, spider webbed wooden patterns once made for sand-casting maritime machine parts: arbors and axles, cams and poppets, spindle – guides, rings and bushings, rotors, pinions, flywheels etc.’

Lanceley and Klippel both carried away truckloads of the material. Lanceley quickly turned the discovery to good effect and produced such classics of contemporary Australian art as The king was in his counting house (NGV, 1964). Klippel set the new materials aside for sixteen years until the NGA ‘commissioned him for a series of bronze sculptures for outside display’. Klippel cast some of the new forms but quickly realised that the wooden patterns were an invaluable sculptural material in their own right. When he began to work directly with the wood patterns, he found that their arrangement was somehow predestined ‘before I knew what was happening things would just gravitate … an incredible magnetism would happen … your mind would know where everything was … it was an incredible phenomenon’.

Robert Klippel, No. 789, 1989, wood assemblage, 147 x 179 x 85 cm. Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne Gift of Robert Klippel 1999 © Andrew Klippel. Courtesy of The Robert Klippel Estate, represented by Annette Larkin Fine Art, Sydney and Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich / Copyright Agency, 2019.

Robert Klippel, No. 789, 1989, wood assemblage, 147 x 179 x 85 cm. Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne Gift of Robert Klippel 1999 © Andrew Klippel. Courtesy of The Robert Klippel Estate, represented by Annette Larkin Fine Art, Sydney and Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich / Copyright Agency, 2019.

To my mind, they are the pinnacle of Robert Klippel’s achievement as a sculptor. They have a playful monumentality quite different from the metal work. They create their own environment. They embrace the virtues of the old and the used, the rubbed and the scarified – wabi and sabi. They speak of a history of endurance, of work and the worn-out. When the AGNSW exhibited one of the most monumental wood pieces in that long gallery that rushes towards the Harbour, its wharves and shipping, its cranes and gantries, Klippel’s sculpture seemed a participant in that world, to vie with its strength and resilience.

At TarraWarra, the wood sculptures were placed in the final gallery, bathed in natural light. More than ever, the sculptures looked like the playthings of giants. It stirred the deeps of the imagination.

Assembled: The Art of Robert Klippel was exhibited at TarraWarra Museum of Art from November 2019 to February 2020. The catalogue of the same name, written by Kirsty Grant, is available from TarraWarra.