- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

New Zealander Colin McCahon is the greatest postwar artist of the two antipodean countries. Hands down. In his own country, McCahon (1919–87) is a household name, and the exhibition A Place to Paint: Colin McCahon in Auckland at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, and the associated publication of Justin Paton’s McCahon Country (Penguin Books), celebrate his centenary. Surprisingly, though, many Australians don’t know McCahon’s work.

- Production Company: Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

How to sum up a lifetime of painting? In Auckland, curators Ron Brownson and Julia Waite sensibly focus on works made in (and about) Auckland, starting from 1958 when McCahon arrived to work at the Gallery, eventually as Deputy Director. Their thoughtful show comprises just three rooms. The first has McCahon wrestling with his new location in subtropical Titirangi, light in kauri trees filtered through the prism of late Cubism, the usual starting place in early 1950s Modernism.

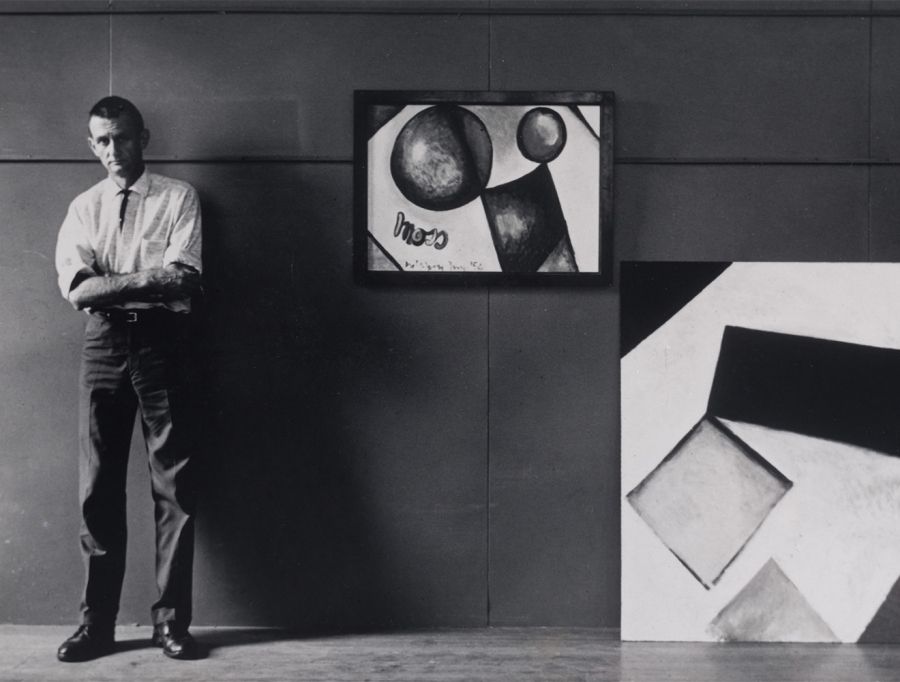

Bernie Hill, Colin McCahon photographed in the Auckland City Art Gallery, 1961, E.H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Bernie Hill, Colin McCahon photographed in the Auckland City Art Gallery, 1961, E.H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

It doesn’t take long: Rocks are for building with (1958), a homage to Cézanne, is about the foundations of his own art, and what he had already learned, at home, or abroad in Melbourne and the United States. Here I give thanks to Mondrian (1961) shows McCahon’s originality: he plays with modernist tropes while looking out of his Auckland window. Nearby, Will he save him? (1959) is a remarkable riff on the theme of Elias the prophet. Sumptuous colours, emphatic black and purple, flashes of red on the right-hand edge of a cross: it is full of hope and foreknowledge. Already, at the start of the Auckland years, McCahon is wrestling with seeing the world, its great questions and events, from that place.

Four multi-panelled works sum up the 1960s, and seeing the massive panorama Landscape theme and variations (series A), just after reading what Justin Paton says about its spiritual freight, was a revelation. The painting’s deep-blue skies are more indigo than the book’s reproductions, the colours more lively, the surface warm and complex. This is a painting to look at for hours, just as McCahon would look at country. It takes time to register variations, to see life. Only last week I was driving in the North Island. It helps to see what McCahon saw, but as he said in 1976, McCahon is not really a landscape painter; he looks at ‘the permanence of people, the fact that people come and go but still persist somehow’.

Colin McCahon, Landscape theme and variations (series A), 1963, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the McCahon Family, 1988. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Colin McCahon, Landscape theme and variations (series A), 1963, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the McCahon Family, 1988. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

I was struck by the complexity of McCahon’s work, its ambition in every sense. Angels and bed number 4: Hi-fi (1976–77) is larger than any contemporary painting I can recall in Australia: paradoxically, its sparseness is replete with references to the deaths of close friends, intellectual companions from a talented generation. Elsewhere in the Gallery, two addenda to the main exhibition flesh out these associations. The Wake: A Poem in the Forest (1958) is McCahon’s largest work, painted just after his return from the United States, and inspired by the ambitious scale of painting there. It’s a magical thing, a response to his friend John Caselberg’s 1957 poem ‘The Wake’ (for Thor, his Great Dane). Here it is displayed in a circular room emulating its original setting. The centrality of poetry makes McCahon more like an East Asian calligrapher than any other artist I know, the intensity of inference captured in every painted letter. This is calligraphy made local: in 1976 McCahon said that his celebrated Northland Panels (1958) had a great deal to do with oriental art, and with New Zealand. The adjacent archive room, one of the best I’ve seen, firmly places McCahon as a curator, teacher, and painter, among his New Zealand community of friends and their concerns. It’s packed with photographs, documents, and posters designed by McCahon, even one fabulous photograph showing him installing sculpture by Jacob Epstein in Auckland Art Gallery, cigarette in mouth.

Colin McCahon, Angels and bed no. 4 : Hi-fi, 1976-1977, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1977. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

Colin McCahon, Angels and bed no. 4 : Hi-fi, 1976-1977, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1977. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust.

And what of McCahon Country, if McCahon is not a landscape painter? The conceptual spine of Paton’s beautifully considered book is travelling the length of New Zealand, its burden the struggle to understand where one stands (in every sense). Paton says it’s a ‘road trip’, and in searching out McCahon’s painting sites, seeing them through McCahon’s interests, he captures the shifting connections in McCahon’s work between actual sites – Otago, Auckland, Muriwai, Te Urewera – viewing them, and then seeing what the implications of that looking might be. As Paton concludes, ‘Perhaps the point is that we look, wherever we happen to be.’ McCahon, a New Zealander who loved and respected his place, is, as Paton notes, an artist for our times in his local grounding. In my view, the necessary questioning of our place as uninvited arrivals in already occupied lands is far better answered in New Zealand than in Australia, both historically and today. Paton’s careful handling of McCahon’s use of Māori language from 1962 onwards underscores this; despite contemporary unease about intercultural borrowing, McCahon’s recognition of Māori language, and Māori presence in the land, was entirely necessary, a sign of his rootedness in his country, a confrontation with its injustices as well as its beauty.

It’s a bumper year for McCahon. Peter Simpson’s scholarly Colin McCahon, (Auckland University Press) will undoubtedly be the key reference for years to come; the first volume appeared in October, the second is due in April 2020. Paton’s book does something quite different: with its beguiling prose and intelligently grouped images, it will open eyes and minds to McCahon’s singular achievement. And there’s still time to get across the Tasman to see A Place to Paint – it runs until 27 January 2020. Otherwise, the National Gallery of Victoria is celebrating the centenary by showing its McCahons until April 2020. You can sit and listen to a 1976 interview with the artist, quietly taking in his lyrical challenge to his world. And at the NGA in Canberra, McCahon’s magnificent Victory over death 2 (1970) can be found in good company with Brâncuşi’s Birds in space (c.1931–36). Now those really are destination works.

A Place to Paint: Colin McMahon in Auckland is being exhibited at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki from 10 August 2018 to 27 January 2020.